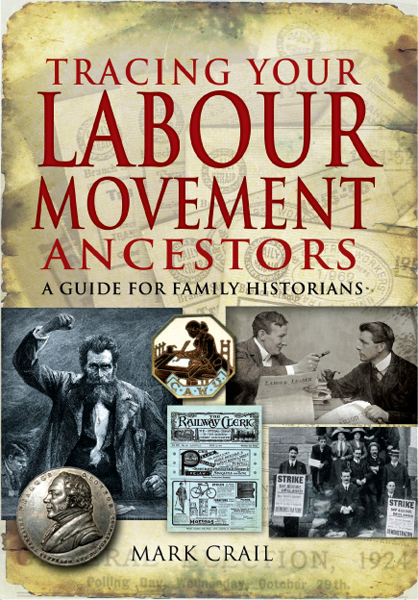

First published in Great Britain in 2009 by

PEN & SWORD FAMILY HISTORY

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Mark Crail, 2009

ISBN 978 1 84884 059 1

epub ISBN: 9781844686827

prc ISBN: 9781844686834

The right of Mark Crail to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England by CPI UK

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of

Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military,

Wharncliffe Local History, Pen and Sword Select, Pen and Sword Military Classics,

Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

CONTENTS

PREFACE

T rade unions are among the largest membership bodies in the country. Even after thirty years of decline, they can still claim nearly eight million members, making them vastly bigger than the RSPCA or Womens Institute, and twice the size of the National Trust. But two centuries ago even to join such an organization was illegal, and to swear the oath required of new members or to engage in combinations to demand higher pay could result in a harsh prison sentence or transportation to the colonies.

The history of the labour movement encompasses lockouts, strikes, demonstrations and sometimes a revolutionary commitment to building a different society. But it is mainly the story of our ancestors working lives. The issues with which trade unions have dealt encompass wages, working conditions, mutual support and friendship. Before the welfare state, the friendly society benefits that trade unions offered were an essential safety net for those who fell on hard times. The branch structure provided a social network not just for those in work but for the retired members, who often received a pension from their unions. And they gave ordinary people a voice in government policies.

The labour movement has always had a strong sense of its own history. The creation myths of the old craft unions now form merely a colourful prelude to accounts of later membership growth, while the initiation ceremonies of the early nineteenth century are regarded as quaint or embarrassing aberrations on the part of the movements pioneers. But the bureaucratic frame of mind required to build and maintain union structures over many years has ensured the survival of records that can help family historians to piece together the lives of ancestors who would otherwise have left little documentary evidence.

In writing these opening paragraphs, I am already acutely aware that I have seemed to use the terms trade union movement and labour movement interchangeably. In fact, although the trade unions are at its heart, the labour movement itself is a wider if rather fuzzily defined entity whose precise boundaries have long been the source of much disagreement.

Within the labour movement will undoubtedly be found the Labour Party which was in part set up by and has been substantially funded for more than a century by the trade unions. The now defunct Communist Party of Great Britain with its strong industrial base and close ties to the unions also has a good claim to be considered a part of the wider labour movement. From there on, things become less certain. What of the many other left-wing parties that rose and fell over the twentieth century from the Second World War dissidents of Common Wealth to the explosion of Trotskyist groups in the 1960s and 1970s? To some extent I have included these as they are unlikely to be covered in many other family history books. The same applies to the cultural and social groups from Clarion cycling clubs to Labour churches that grew up organically within the labour movement.

I have, however, drawn the line at attempting to track the hundreds of single-issue campaigns from the Peace Pledge Union to the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, the Anti-Nazi League to the Anglo-Soviet Friendship Society. Although labour movement organizations played key roles in establishing and running many of these groups, they were from the start intended to be wider than or even separate from the parties that spawned them either from a genuine intent to build a broad coalition in support of their cause, or in some cases to become front organizations for their parent bodies, useful tools to extend political influence in a sometimes dubious manner.

My own association with the labour movement began in 1979 when, with monumentally bad timing, I joined the Labour Party just as millions were deserting it and the best part of a generation of Conservative government was about to begin. A year later I became a member of the National Union of Journalists, just as trade union membership hit its historic high and began a precipitous and apparently inexorable decline.

My interest in family history took another twenty-five years to develop, but when I began my research I was delighted to discover that family tradition was correct and we did, indeed, have an active Chartist in our midst. Alas, James Grassby, my great-great-great-grandfather, was no better in his political timing than me. After serving the movement for more than a decade in a variety of roles, he became general secretary of the National Charter Association in 1851. Soon afterwards, the organization imploded, leaving James and his fellow members of the executive to pay off its substantial debts.

Since James was followed by a number of generations who eschewed the labour movement and rose to local prominence in the Conservative Party and freemasonry instead, I can boast no other family ties to trade union and labour politics. Even so, I find myself fascinated by the organizational history of the labour movement, its mergers, splits and schisms, and by its rich visual culture of banners, badges, memorabilia and ephemera.

ARRANGEMENT OF THIS

BOOK

T he book is arranged in ten chapters. It begins with a guide to the types of record you may encounter while researching a labour movement ancestor and introduces some of the principal archives for this type of material. Where full contact information for an archive has been included in Chapter 1, I have not repeated it elsewhere in the book.

There are then four chapters dealing chronologically with the history of trade unions over the past two centuries. The experiences of individual trade unionists during each of these periods will, of course, have been incredibly diverse, depending on their trade, location, the prevailing economic conditions at any particular time, and of course the depth of their involvement in trade unionism. Nonetheless, I have tried to illustrate some of this by selecting a couple of real individuals in each period and briefly telling their life story.

The three chapters which follow trace the development of the political work of the labour movement, dealing in turn with Chartism, the Labour Party and its forebears, and the Communist Party of Great Britain and other left-wing parties. A further chapter introduces some of the many social and cultural organizations that have grown out of the labour movement, from cycling clubs to socialist Sunday schools. The main body of the book concludes with a short chapter on the development of the electoral franchise since 1832 and suggests how electoral registers and related records might also help you to trace your labour movement ancestor.

Next page