History of Andersonville Prison

UNIVERSITY PRESS OF FLORIDA

Florida A&M University, Tallahassee

Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton

Florida Gulf Coast University, Ft. Myers

Florida International University, Miami

Florida State University, Tallahassee

New College of Florida, Sarasota

University of Central Florida, Orlando

University of Florida, Gainesville

University of North Florida, Jacksonville

University of South Florida, Tampa

University of West Florida, Pensacola

History of Andersonville Prison

Revised edition

Ovid L. Futch, with a new introduction by Michael P. Gray

University Press of Florida

Gainesville/Tallahassee/Tampa/Boca Raton

Pensacola/Orlando/Miami/Jacksonville/Ft. Myers/Sarasota

Copyright 1968 by the Board of Commissioners of the State Institutions of Florida

Reprinted 1999 by the University Press of Florida

Revised edition copyright 2011 by the Estate of Ovid L. Futch

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

All rights reserved

18 17 16 15 14 13 6 5 4 3 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Futch, Ovid L., 19251967.

History of Andersonville Prison / Ovid L. Futch; with a new introduction by Michael P. Gray. Rev. ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8130-3691-5 (acid-free paper)

1. Andersonville PrisonHistory. 2. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Prisoners and prisons. 3. Prisoners of warAbuse ofGeorgiaAndersonvilleHistory19th century. 4. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Social aspects. 5. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Atrocities. I. Title.

E612.A5F8 2011

973.7'71dc22

2010045380

The University Press of Florida is the scholarly publishing agency for the State University System of Florida, comprising Florida A&M University, Florida Atlantic University, Florida Gulf Coast University, Florida International University, Florida State University, New College of Florida, University of Central Florida, University of Florida, University of North Florida, University of South Florida, and University of West Florida.

University Press of Florida

15 Northwest 15th Street

Gainesville, FL 32611-2079

www.upf.com

Contents

Preface

Many writers have dealt with Andersonville Prison, but few of them have attempted to approach the subject objectively. No one has written a complete account of the prison based on a scholarly sifting of available evidence. The purpose of this study is to determine what happened at Andersonville, to examine the conditions that resulted in high mortality among the prisoners, and to consider the question of responsibility for those conditions.

No attempt has been made to compare Andersonville with other Civil War prisons. I have refrained from speculating on what might have resulted from continuation of a free exchange of prisoners. Rather, my approach has been to regard the cessation of exchanges as an accomplished fact that did not relieve either side of the obligation to provide for captives taken in battle.

I am deeply indebted to Professor Bell I. Wiley, who drew my attention to this topic and whose skillful guidance has been invaluable in the research and writing. Mr. Joseph P. Renald, Chicago, Illinois, generously shared his incomparable knowledge of the early career of Henry Wirz. Especially helpful information and suggestions have been given by Mrs. Violet Moore, librarian, Montezuma Carnegie Library, Montezuma, Georgia; Mr. Lonnie G. Downs, Montezuma; Mrs. Marian Tate, library assistant, Special Collections Division, University of Georgia Library, Athens; and Dr. Horace Montgomery, Professor of History, University of Georgia. The research that has gone into this endeavor was made possible by a grant from the Southern Fellowships Fund.

Grateful acknowledgment is also given to Mrs. Ovid L. Futch for long hours of proofreading and typing, and for encouragement and inspiration.

was incorporated in Andersonville Raiders, Civil War History, II (December 1956), 4760. I am grateful to Civil War History for permission to reprint these chapters.

Ovid L. Futch

Introduction

Advancing Andersonville

Ovid L. Futch as Prison Micro-Monograph Pioneer

Michael P. Gray

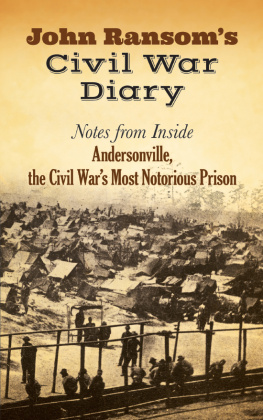

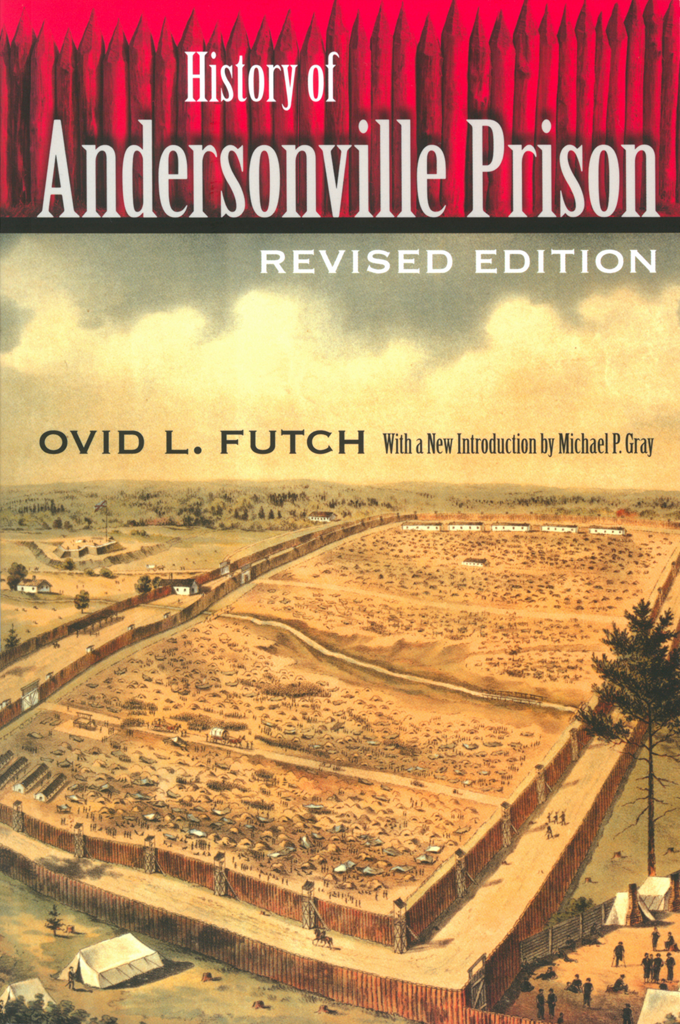

A prison that was built in southwest Georgia during the latter stages of the Civil War achieved such notoriety that its very name resonates with controversy to this day. Despite its brief existence of only one year and two months, the camps history is overpowering. From prisoners who endured a noxious confinement in a stench-filled stockade to politicians quarreling in postwar debates, stories of the scourge it caused traveled beyond its wooden walls into the halls of Congress; Andersonville became synonymous with the suffering of about 45,000 prisoners, nearly 13,000 of whom died.

Though many have dedicated attention to this prison (also known as Camp Sumter), it has taken time for academic historians to proceed with a scholarly treatment of this camp. There is a quagmire of biased testimony produced by former inmates and those who claimed to have been imprisoned, for whom writing a sensational account that demonstrated alleged pain and suffering in prison might be worth a pension, or even royalties. These complications have posed serious problems in understanding the history of Andersonville Prison.

Civil War prison historiography has seen a steady improvement since a 1988 appeal from James M. McPherson in his Battle Cry of Freedom, which noted the dearth of scholarship on this controversial yet often overlooked topic. The Pulitzer Prizewinning historian noted at the time

Hesseltines expertise on prison pens prompted an invitation to guest edit a special volume of Civil War History. Having recently concluded an appointment as president of the Southern Historical Association, he recognized the importance of further examination into an area that remained underexplored thirty years after he had published his own study of it. As editor, Hesseltine recruited other historians both from academia and from the public sector. The resulting collection was published in 1962 and alsoa decade latercompiled into a book that has become both widely read and highly respected. This collaboration marked the first time a group of historians had meaningfully considered the camps. Hesseltine began with a short introduction, which was followed by essays from the other contributing historians on Southern and Northern compounds, including Minor H. McClain on Fort Warren, T. R. Walker on Rock Island, James The anthology was an excellent, multi-faceted work of scholarship on various prisons and personalities but was still merely a slim volume designed primarily to spark the interest of historians.

Top scholars were still waiting for more work to be done within the field. In 1998, a decade after McPherson made his petition, Gary Gallagher poignantly reiterated that prisons and prisoners of war rank among the most controversial but least studied aspects of the American Civil War. After nearly seventy years, Hesseltines Civil War Prisons remains the most useful introduction to a topic that has generated more emotional debate than sound scholarship. Since then, modern macro-monograph writers have struggled to meet Hesseltines standard. The topic of Civil War prisons is already complex when each camp is examined individually, let alone when the field is surveyed in its entirety. More than 150 camps existed, each with a unique history. Many, containing a society developing on the inside and affecting host communities on the outside, gave rise to economies that crossed through both. Every member of local personnel entered into the equation, from commandant to contractor. Recently, however, scholars have concentrated almost exclusively on policy history, which lends itself to overarching themesand often to generalizations. Social and cultural historians might be especially disappointed with the current state of prison macro-studies.