Preface

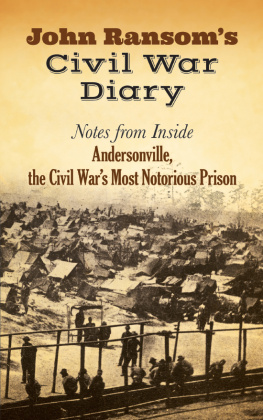

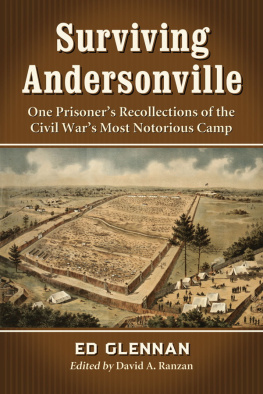

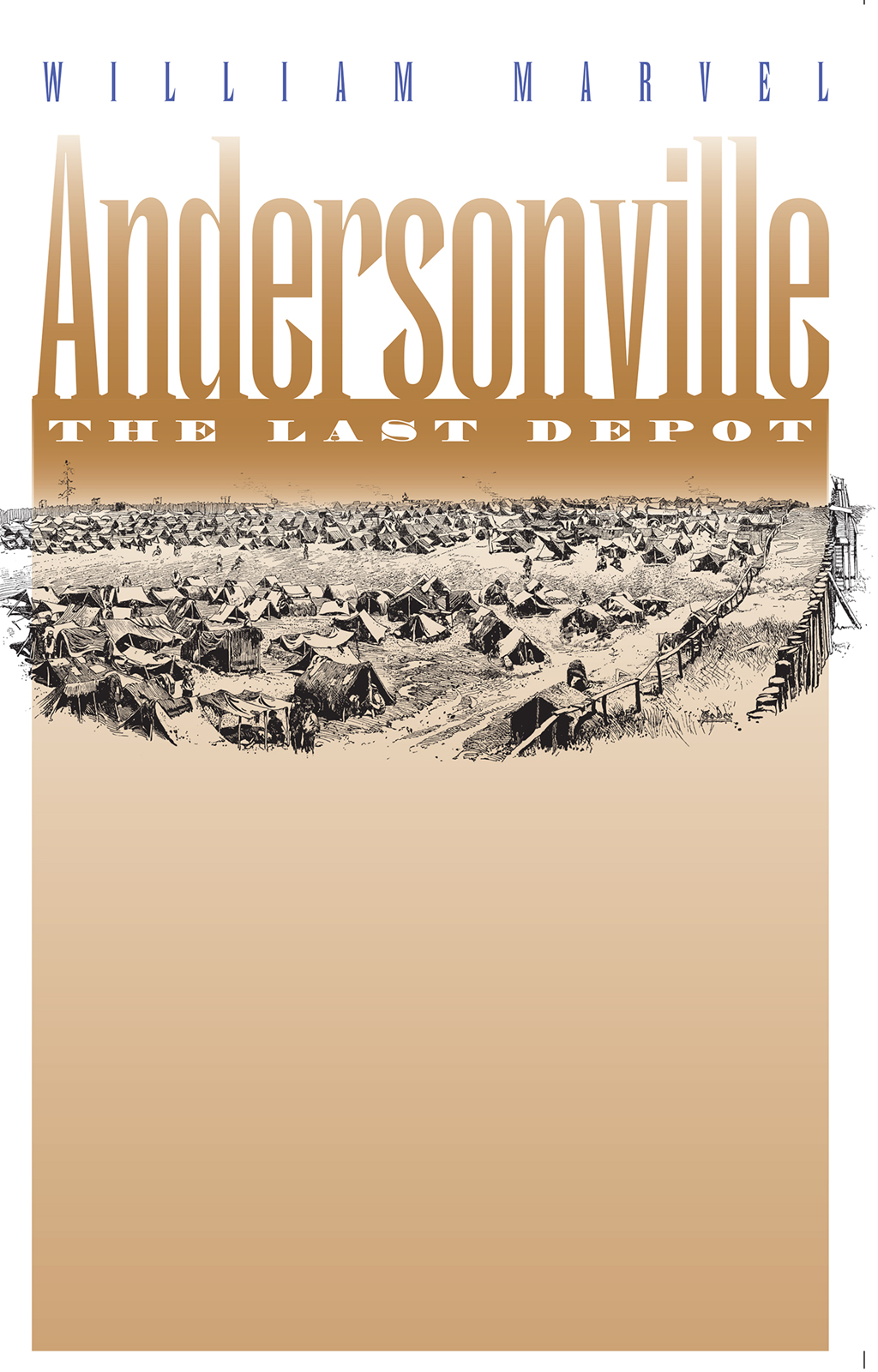

Some 41,000 men shuffled into the prison stockade at Anderson Station, Georgia, between February of 1864 and April of 1865, Of these, perhaps 26,000 lived long enough to reach home. Theirs was undoubtedly the most unpleasant experience of the Givil War, but, almost without exception, those who wrote about Andersonville appear to have exaggerated their tribulations at that place. Some did so deliberately, for political reasons or simply because accounts of prison misery sold well in the postwar North. Others forgot personal acts of kindness, regurgitating tales of horrible cruelties that they never witnessed because, as one of them reasoned, they must have been true. In many cases they based their anecdotes on testimony from the trial of Henry Wirz, the transcript of which runs heavy with some of the most absurd hearsay that any American judge ever permitted to stand.

Literary demands may have driven former prisoners to enliven their recollections with grisly imaginings or borrowings, if only to avoid infecting their readers with the sheer tedium of Andersonville. Memories of their helplessness at the hands of their captors and crystallized suspicions that their deprivation was an act of conscious design may also have provoked a certain license with the truth. These men did not, however, have to embellish their accounts to produce a picture of immense suffering: the prison and the circumstances provided that without any infusion of malice.

Much effort has been expended by various partisans to prove that Southern spite against prisoners or Northern intransigence on the exchange question was responsible for this tragedy. Surviving documents seem to discredit any accusation of deliberate deprivation, unless one takes the position that the Richmond government should have devoted a greater proportion of its dwindling resources to its prisoners than to its own army, but thorough examination of the exchange question would require the better part of a book. This will not be that book. Clearly the breakdown of prisoner exchange was responsible for the lengthy imprisonments that allowed vitamin deficiency to kill and cripple so many, but the real cause of that breakdown is less certain.

It was the Federal government that suspended the exchange cartel, first in response to disagreement over numbers and then in protest of the Confederate refusal to repatriate black soldiers. At one point it appeared that the two sides might work that out, except perhaps for those prisoners who were recognized as former slaves, but the Federal government insisted on absolute equality for all black prisoners: it could do no less without appearing to foresake them. Conversely, as hungry for manpower as it was, the Confederacy could not comply without renouncing the very reason for its existence. Northern stubbornness on that point puzzled equally resolute Southerners, leading them to suspect that this was merely an excuse for keeping the large preponderance of prisoners held in Union prisons. In the summer of 1864 Ulysses Grant let it slip that there was at least a grain of truth to that argument: as hard as it was on those in Southern prisons, he contended, it would be kinder to those still in the ranks if each side kept what prisoners it had, since that would end the war sooner.

As important as the exchange question was to the prisoners, the finer points of the debate do not bear particularly on what actually happened at Andersonville. It may not even be possible to determine whether the issue of black soldiers was a pretense, or whether the more pragmatic motive evolved during the cartels suspension, since intentions varied widely among those who held power. Grants implied policy of attrition was just as legitimate as the administrations stated motive was highminded: if it was adherence to such a policy that led to the deaths of thousands who might otherwise have lived, it probably saved even more lives that might have been lost, North and South, by prolongation of the conflict.

That would have been a tough bill of goods to sell in 1865, had Grants reasoning been public knowledge. Even the principle of equal treatment for black prisoners held little sway with many in the North: Lincolns own secretary of the navy privately denounced the obstinacy over former slaves. The inhabitants of Andersonville felt particularly bitter on that account. Prison officials played the card for all it was worth, prompting great numbers of prisoners to express contempt for the Lincoln administration, which they felt had abandoned them for the confiscated contrabands.

Back home, many of the prisoners families shared that sentiment. It therefore behooved the victors to establish that enemy malevolence had caused it all rather than a matter of lofty principle or a conscious practical policy of the victims own government. That aim proved consistent with the politics of the bloody shirt, and military justice provided the requisite scapegoat. With that pronouncement one frail Swiss immigrant went to the gallows and Andersonville came to signify all that was evil in the hated Confederacy.

Andersonville

AndersonvilleOnly the winners decide what were war crimes.

Garry Wills

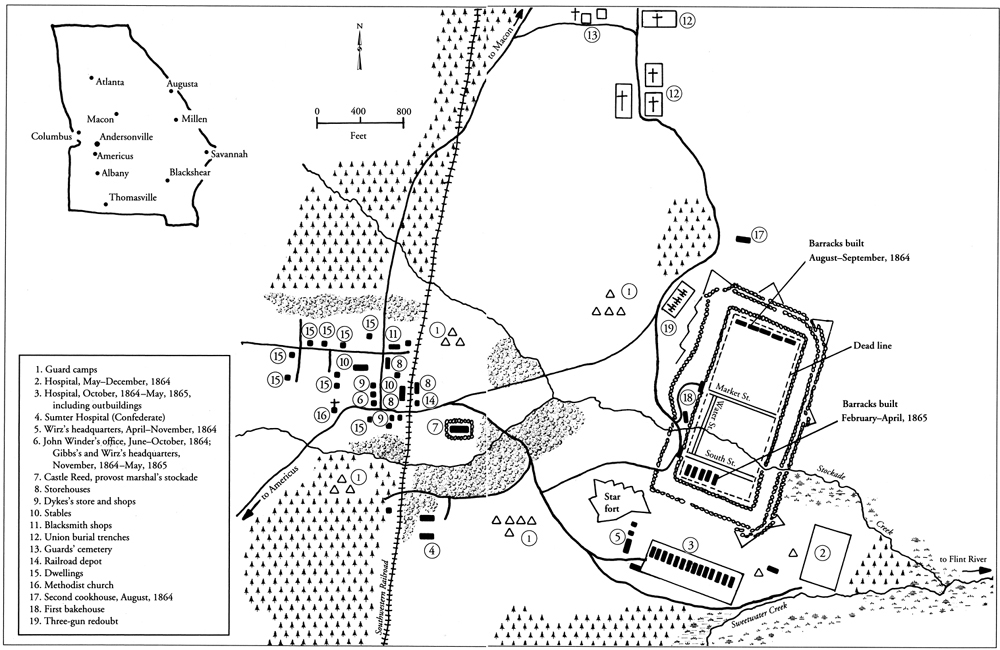

Andersonville, Georgia, and Andersonville Prison, 18641865. Adapted from a map by Blake A. Magner.

1 I Find Me in a Gloomy Wood

As on any other day, the world spent Tuesday, November 24, 1863, spinning the thread of tomorrows events from the flax of yesterdays. In Moscow a former political prisoner struggled to document the horrors of his experience; from Copenhagen a new Danish king evoked the wrath of the growing Prussian empire when he cast a covetous eye on two German duchies; at the mouth of the Seine a young artist who would help change the complexion of painting sketched the rugged coast of his native Normandy; off Japan a British frigate avenged the execution of a countryman with a surprise bombardment of the city of Kagoshima; in the wind-whipped autumn chill that reminded him of his Norwegian homeland, a laboring man in Winchester, Wisconsin, learned that his nameKnud Hansonhad been drawn that very day from a tumbler full of such names, and now he would have to fight in the war that raged across the American continent.

Andersonville

Andersonville