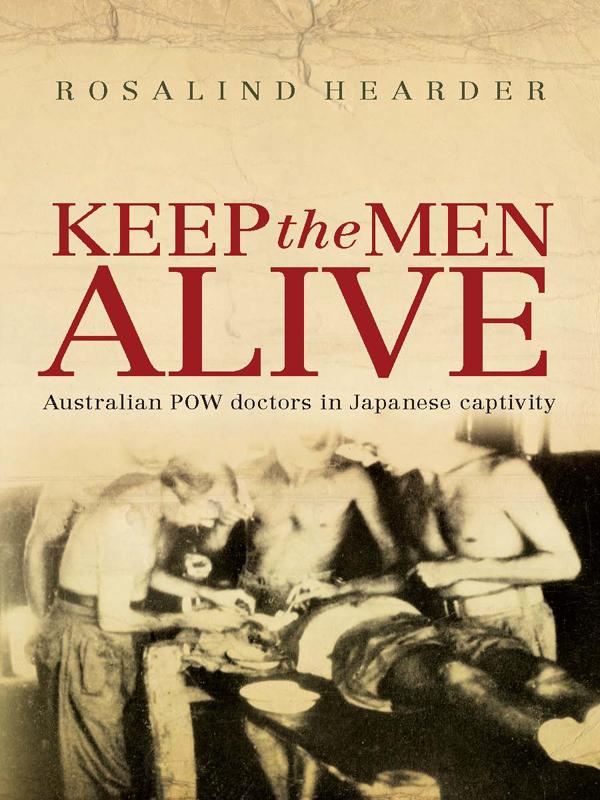

KEEP the MEN

ALIVE

ROSALIND HEARDER

KEEP the MEN

ALIVE

Australian POW doctors in Japanese captivity

First published in 2009

Copyright Rosalind Hearder 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Interview extracts from The Australians at War Film Archive are reproduced with permission, courtesy of Mullion Creek Productions Pty Ltd, P.O. Box 2540, Orange, NSW, 2800, Australia.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available

from the National Library of Australia

www.librariesaustralia.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74175 738 5

Internal design by Lisa White

Index by Puddingburn Publishing

Set in 11/16 pt Minion Pro by Bookhouse, Sydney

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

To John Lack

All wars of any magnitude and duration must be won primarily on the medical front.

P ROFESSOR S IR P ETER M AC C ALLUM

Unless otherwise stated, all officers referred to in this book are Australian medical doctors. In each chapter, the first time each doctor is mentioned his rank will be used, and from then on only his surname. Appendix A lists all Australian POW doctors in Japanese captivity in alphabetical order, with their ranks and units for ready reference. Medical or combatant officers of any other nationality are so noted.

All unattributed quotes are from interviews conducted between former POWs and the author.

Where would we have been without the doctors? I wonder how many of us would be around today but for them?

F ORMER A USTRALIAN P OW

In 1946 Dr Rowley Richards arrived late to the inaugural postwar meeting of the 2/15th Field Regiment Association, a regiment that had experienced Japanese captivity during World War II. Sitting at the back of the room, he watched as the members began the process of appointing the Association President. Somebody nominated a former POW (Prisoner of War) combatant officer and the response was overwhelmingly negative. To his surprise, Richards then heard himself being nominated. He recalled, Now the troops saw me as neither fish nor fowl. I was not... one of the officers in authority I suppose, they didnt identify me there. They identified me with somebody who was trying to help them. So I became president and I still am. That he still holds this position today is a mark of the esteem in which he is held.

Four years earlier, a much younger Captain Rowley Richards, recently graduated in medicine from Sydney University, found himself a prisoner of Japanese forces after the fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942. He was joined by 22,000 fellow Australian servicemen and many thousands more British, Dutch and American troops. For the next three and a half years, Richards would struggle daily to keep men alive in the brutal environment of Japanese imprisonment. But he was not alone in his effortsanother 105 Australian doctors had also been captured, and like Richards, would spend the war working tirelessly for the welfare of fellow POWs.

Despite this groups best efforts, one-thirdapproximately 8,000 Australian soldiers and sailors died in Japanese captivity. Those who survived would return home with varying degrees of physical and psychological impairment, which some would endure for decades after the war. While imprisonment under other Axis powers was by no means easy, the prisoners of the Japanese were the most unfortunate of an unfortunate lot. Of the 8,000 Australians in POW camps in Europe, 3 per cent died, compared to 36 per cent in the Japanese camps.

Japanese internment was not the same experience for all Australian prisoners. Some spent most of their time as POWs in Changia huge, well-organised and comparatively autonomous camp in Singapore. Others were sent with work parties to the primitive conditions and oppressive climate of Burma or Borneo, where they were forced to build their own camps, and were frequently moved from camp to camp under the constant vigilance of their captors. Thousands of Australian POWs, including 44 medical officers, spent almost a year in a horrific 400-kilometre stretch of jungle building the BurmaThai Railway. A third of the total Australian POW deaths in Japanese imprisonment occurred here. A small number of men, such as those on Ambon and Hainan islands, spent their captivity in total isolation, while others were eventually moved from tropical Singapore and Malaya to the freezing environments of Manchuria (a Japanese-controlled area of China) or the Japanese home islands.

In all these places, Australian doctors accompanied their fellow prisoners and did whatever they could to keep them alive, often at great personal physical and psychological cost. They faced complex demands and pressures, for which there were no precedents, and often assumed positions of importance far outweighing their normal military role.

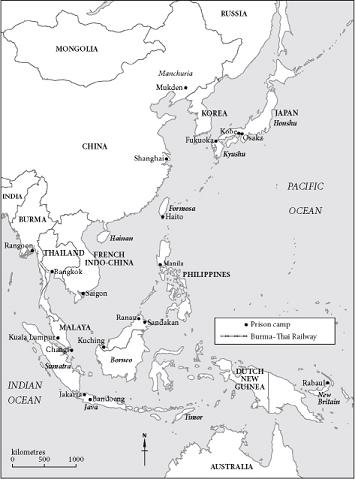

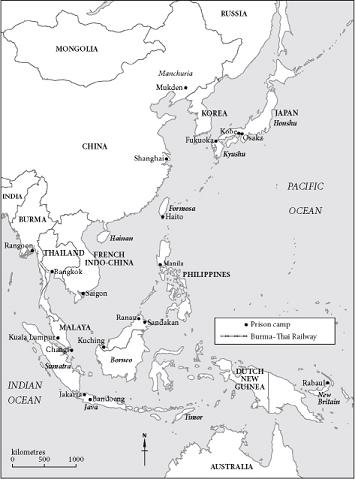

MAP 1

Japanese military forces held Australian and other Allied POWs in camps all over Asia. Major areas of concentration are identified here.

These doctors ranged in age from Captain Roy Markham Mills, who was just 24 years old when he was captured, to Colonel Edward Rowden White, captured at 58. Mills joined up in 1940 at the age of 22. He had no previous military experience but, like many young men at the time, had a desire to do his bit for his country. White, on the other hand, had decades of surgical experience behind him. He had served in World War I and remained in the militia throughout the inter-war period.

These two men were the youngest and oldest of the Australian POW doctors in World War II, and represented the opposite extremes of experience, both medical and military. At the beginning of the war it would seem that they had little in common; however, as captivity was soon to show, background differences became less marked when the challenges of imprisonment created a shared bond.

Regardless of their previous experience, age or military rank, in Japanese captivity all Australian POW doctors faced an overwhelming combination of factors destined to kill many of their men: debilitating climate, rampant disease, starvation, physical abuse and forced labour. Many Japanese POW camps were without any built infrastructure, and doctors had little or no diagnostic or sterilising equipment, vitamins, or everyday medical supplies such as syringes and bandages. Captivity demanded adaptability, forcing many doctors to be surgeons, dentists, anaesthetists and psychiatrists, whether or not they had specialist knowledge. While in a camp on the BurmaThai Railway for example, South Australian doctor Captain Colin Juttner, trained as an ophthalmologist, recalled: They needed someone to go out with the working parties who was an eye man... Well, up on the Railway, I was supposed to be the bloke doing the eyes but I finished up being the bloke doing the amputationslegs and arms.

Next page