SPEAKERS CORNER is a provocative series

designed to stimulate, educate, and foster discussion on

significant public policy topics. Written by experts in a

variety of fields, these brief and engaging books should

be read by anyone interested in the trends and issues

that shape our world.

Foreword by Senator John Kerry

Edited by Dr. James M. Ludes

American Security Project

Uncensored

2009 American Security Project, unless otherwise noted

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Iraq uncensored : perspectives / American Security Project ; edited by James M. Ludes.

p. cm. -- (Speakers corner)

ISBN 978-1-55591-703-6 (hardcover)

1. Iraq War, 2003- 2. Iraq War, 2003---Influence. 3. National security--United States. 4. Military policy--United States. I. Ludes, James M. II. American Security Project.

DS79.76.I72715 2009

956.70443--dc22

2009011509

Printed on recycled paper in Canada by Friesens Corp.

0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

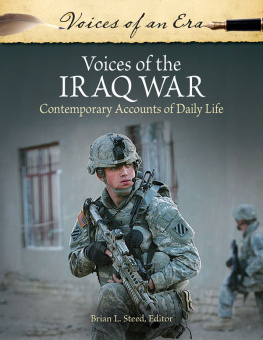

Cover image Gary Paul Lewis | Shutterstock

Fulcrum Publishing

4690 Table Mountain Drive, Suite 100

Golden, Colorado 80403

800-992-2908 303-277-1623

www.fulcrumbooks.com

To those who serve

Acknowledgments

This book is the sum of its parts. The authors deserve every credit for their insightful contributions. To my colleagues at the American Security Project, especially Amy Gergely, who worked tirelessly on early drafts of many of these essays, Bernard Finel, Holly Gell, Selena Shilad, and Christine Dehn, I owe a special debt of gratitude. Any failures in this volume, however, are mine.

I also want to thank my family and friends for putting up with me and my generally overbooked schedule. A special debt of gratitude is reserved for Anne, who inspires me in profound ways, and for my parents, Elaine and Jake, who make everything possible.

Foreword

Senator John Kerry

No war is easy. Combat is never simple. But Iraq in particular has failed to submit itself to even relatively simple or easy shorthand.

Just think, in the last six years Iraq has been many things to many people, some seemingly contradictory: a failure of diplomacy to keep weapons of mass destruction out of the hands of a dictator; a preemptive war to achieve what diplomacy was not given the time to accomplish; a demonstration of the brilliance of American troops; a failure to listen to generals and State Department experts about what would come next; an ideological overreach to transform an entire region; a massive intelligence failure; an insurgency, teetering on the brink of sectarian civil war; the start and stop and start again of reluctant civil institutions; a Sunni awakening complemented by a new military and political strategy; an orderly redeployment of troops leaving Iraqis largely responsible for their own future.

All this and morethe good, the bad, the uglythe layers of policy to be dissected and debated from Americas war of choice in what was once called the cradle of civilization will occupy historians for generations.

And the last chapter is now largely in Iraqi hands.

Yes, war has been with us since the dawn of man. Our effortsour dreamsof making it less common have been frustrated time and again. Institutions, treaties, and theories advancing this cause have all collapsed under the weight of history.

But even by that standard, Iraq is different. Seldom have the conventional definitions of foreign policy positions been turned on their heads so much as they were in this war.

It may be too early to draw definite conclusions about the Iraq war, but it is not too early to begin asking the question. This effort by the American Security Project is among the first to ask a broad cross section of observers: What should we learn from the Iraq war?

The purpose is not to pave the way for more Iraqs or to find some convenient new theory to prevent the next Iraq, but to learn from this experience so that we, as a nation, may gain wisdom, not simply to fight some future war betterbut to learn valuable lessons about people and human events so that we can advance the cause of freedom and security, peace and justice, and so that we will be better equipped to be an America that only goes to war because it has to, never because we want to.

Iraq Uncensored begins a dialogue about the lessons of the Iraq war that will last for decades. No matter what you believe about the warits wisdom, its purpose, or its costit is every Americans duty to at least grapple with the issues raised by it. Whether we admit it or not, the Iraq experience will shade, for good or for bad, the foreign policy debate for years to come. We are better off acknowledging that fact head-on than ignoring it as inconvenient or thinking we can hit the reset button for foreign policy.

Some authors will disagree with each other on the lessons, and so will readers. This isnt easy. But no war is. And thats the point.

Introduction

James M. Ludes

Over the course of eighteen months, the American Security Project put the following question to some of the most creative minds in national security: What is the single most important lesson the United States should learn from the war in Iraq?

The answers we received are published in the pages that follow. They are neither pro-war nor antiwar. They run the gamut from how to better approach similar operations to pleas to never undertake such missions again. Each response reflects the unique perspective of its author. Collectively, they reveal a greater diversity of opinion on the war in Iraq than can be found in recent public-opinion surveys on the topic. While the public has rejected the strategic utility of the war, there are many analysts who continue to focus on what might have been done differently at the tactical level.

At best, we can conclude that the Iraq war remains a divisive issue in America. Any effort to draw lessons from the war risks becoming bogged down in partisan debate about the way the Bush administration led the country to war. But a discussion of this importance cannot be dismissed as partisan grandstanding. This is a conversation we must have as a nation. For the truth is that historians will spend decades examining this conflict, its causes, its conduct, and its consequences. In the meantime, we face an urgency to learn from the experience so that any new decisions about war and peace are better informed, more thoroughly vetted, and more rationally made.

In the first section, The Coming of the War, Paul Pillar and Bishop John Bryson Chane reflect on the war from inside the intelligence community and inside the peace movement, respectively. Robert Gallucci looks at the case for war and concludes that in the future, the United States should only go to war when compelling reasons can be articulated by the administration and withstand examination by Congress and the Ameri