Jeffrey K. Tulis

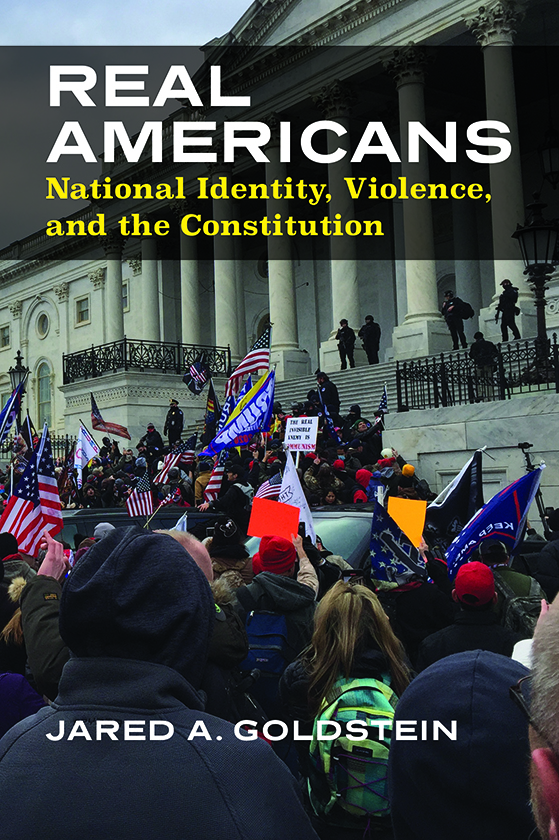

Real Americans

National Identity, Violence, and the Constitution

Jared A. Goldstein

University Press of Kansas

University Press of Kansas

2022 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045 ), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Goldstein, Jared A., author.

Title: Real Americans : national identity, violence, and the constitution / Jared A. Goldstein.

Description: Lawrence : University Press of Kansas, 2021 . | Series: Constitutional thinking | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021018746

ISBN 9780700632831 (cloth)

ISBN 9780700632848 (paperback)

ISBN 9780700632855 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Constitutional lawPolitical aspectsUnited States. | Constitutional historyUnited States. | United StatesPolitics and government.

Classification: LCC KF 4552 .G 65 2021 | DDC 342.7302 /dc

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/ 2021018746 .

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in the print publication is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z 39.48 1992 .

To my father, David Goldstein, who despite everything always believed in e pluribus unum; to Leonard Zeskind, who has fought tirelessly to expose the reality of hate movements; and to Louis Pollak, whose love for the Constitution inspired and baffled me.

Contents

Series Editors Preface

One of President Barack Obamas favorite declarations, particularly when something truly amiss, such as racist violence, had happened within the United States, was that the action did not truly represent the United States. This is not who we are, he often said. He was certainly not alone in his use of that meme. Indeed, President Joe Biden, responding to the horrific massacre of six Asians in Atlanta (as well as at least two of their non-Asian customers), described the attack as un-American. The point of the assertion is to suggest that we, that is, both the speakers and the presumably appreciative audience, represent the real America, who would never behave so badly as the individuals or groups being criticized.

The Supreme Court often engages in similar rhetoric. For example, in Bolling v. Sharpe the 1954 case arising from Washington, DC, that was a companion case to the far better known Brown v. Board of Education Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote, Classifications based solely upon race must be scrutinized with particular care, since they are contrary to our traditions. Objectionable they may be, but it requires a willful ignorance of American history to believe that they are necessarily contrary to the more lamentable aspects of our traditions. What joins Obama, Biden, and Warren is the suggestion that the miscreants committing the ostensibly aberrant behavior are in some profound sense not really American themselves, not part of the American family that generates the complex mosaic of American political traditions (plural). Part of American exceptionalism may in fact be an anxious concern about what it means to be an American and to identify a singular American political tradition. This in turn carries with it the concomitant desire to identify those who are un-American, not really one of us.

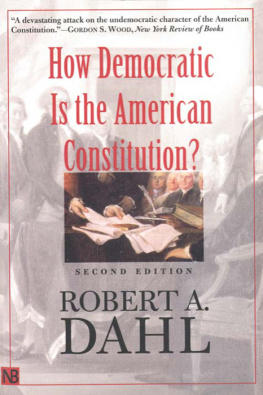

How does this relate to the extraordinaryand, alas, all too timelybook by Jared Goldstein, with its evocative title, Real Americans: National Identity, Violence, and the Constitution ? The answer is simple, though not at all simplistic. Goldstein identifies an important strand of American political thought that he labels constitutional nationalism. That is, to be an American is to stand with, and by, the Constitution. Whatever may be our differences in an America that has always, from its beginning, contained what Walt Whitman identified as multitudes of quite different peoples, we are united, it is often claimed, by our beliefindeed, our faith in and veneration forthe centerpiece of the American civil religion, our Constitution. Consider only the oath taken by anyone becoming a member of the United States military, which begins by the oath takers solemnly swear[ing or affirming] that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same. In fact, Article VI of the 1787 Constitution requires that all public officials, at whatever the level of government, take an oath of loyalty to the Constitution. And, of course, the Constitution specifies the very words of the oath to be taken by a president, who solemnly swears to the best of my Ability, [to] preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States. It would be surprising if many readers of this book have not themselves, at one point or another in their lives, taken such an oath.

The problem is that Americans scarcely agree on what exactly counts as faithful compliance with the solemn oath, sworn by many in the name of God. Indeed, the military oath quoted above continues with the promise that I will obey the orders of the President of the United States and the orders of the officers appointed over me, according to regulations and the Uniform Code of Military Justice. So help me God. But does this mean that all orders, even those that might be regarded as manifestly illegal under the Code of Military Justice itself, are to be obeyed? Consider in this context the statement by the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 2020 that their loyalty was to the Constitution and not to President Trump, which for many carried the implication that they would refuse to obey what they considered to be unlawful orders given by the ostensible chief executive and commander in chief.

Philosophers often refer to essentially contested concepts, by which they refer to particular notions that carry a positive valencethink of democracy, justice, or nondiscriminationbut are, nonetheless, subject to multiple, and often conflicting, interpretations. Not surprisingly, people can get especially angry if one suggests that their notion of one of these concepts is fatally flawed. So it is with the term of what might be called constitutional fidelity. One might agree that it is very important and then discover that there are very different notions of the term. It is well to recall that Southern secessionists in 1860 1861 claimed to be faithful to the true Constitution that they arguedwrongly, no doubt, in the eyes of most of uswas being violated by their adversaries, including Abraham Lincoln. Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee, both graduates of West Point who had taken vows of constitutional fidelity, did not view themselves as traitors waging war against the Constitution. Abraham Lincoln obviously had a very different view, and , Americans died in the ensuing dispute over what constitutional fidelity really meant. Perhaps this only underscores the reality that what might be called intra-family disputes, including those within the American family, are often the most acrimonious of all.

University Press of Kansas

University Press of Kansas