BLESSED ARE THE PEACEMAKERS

BLESSED ARE THE

PEACEMAKERS

Martin Luther King Jr.,

Eight White Religious Leaders, and

the Letter from Birmingham Jail

S. JONATHAN BASS

UPDATED EDITION

With a New Foreword by PAUL HARVEY

and a New Afterword by JAMES. C. COBB

Louisiana State University Press

Baton Rouge

Published by Louisiana State University Press

www.lsupress.org

Copyright 2001, 2021 by Louisiana State University Press

All rights reserved. Except in the case of brief quotations used in articles or reviews, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any format or by any means without written permission of Louisiana State University Press.

Louisiana Paperback Edition, 2002

Updated Edition, 2021

Designer: Barbara Neely Bourgoyne

Typeface: Sabon

Typesetter: Coghill Composition, Inc.

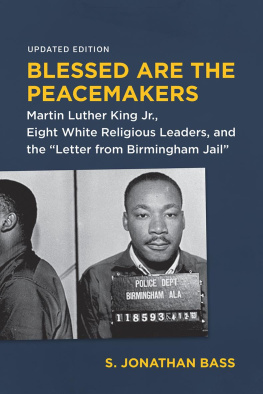

Cover photo: Martin Luther Kings police mug shot from Friday, April 12, 1963. Courtesy of the Birmingham Police Department.

Martin Luther King Jr.s Letter from Birmingham Jail is reprinted by arrangement with The Heirs to the Estate of Martin Luther King Jr., c/o Writers House as agent for the proprietor New York, NY. Copyright 1963 by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Renewed 1991 by Coretta Scott King.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bass, S. Jonathan, author. | Cobb, James C. (James Charles), 1947 writer of afterword. | King, Martin Luther, Jr., 19291968. Letter from Birmingham Jail.

Title: Blessed are the peacemakers : Martin Luther King Jr., eight white religious leaders, and the Letter from Birmingham Jail / S. Jonathan Bass.

Description: Updated edition / with a new foreword by Paul Harvey and a new afterword by James C. Cobb. | Baton Rouge : Louisiana State University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020048964 (print) | LCCN 2020048965 (ebook) | ISBN 978-0-8071-7478-4 (updated edition) | ISBN 978-0-8071-7591-0 (pdf) | ISBN 978-0-8071-7592-7 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: King, Martin Luther, Jr., 19291968. Letter from Birmingham Jail. | Civil disobedienceAlabamaBirminghamHistory20th century. | Civil rights movementsAlabamaBirminghamHistory20th century. | African AmericansCivil rightsAlabamaBirminghamHistory20th century. | ClergyPolitical activityAlabamaBirminghamHistory20th century. | ClergyAlabamaBirminghamBiography. | Birmingham (Ala.)Race relations.

Classification: LCC F334.B69 N415 2021 (print) | LCC F334.B69 (ebook) | DDC 323.092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020048964

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020048965

To Jennifer

for her unfailing

love, support,

and confidence

Contents

by Paul Harvey

by James C. Cobb

Illustrations

Foreword

PAUL HARVEY

Years before Nolan Harmon appeared as one of eight Birmingham clerics who served as targets and foils for Martin Luther King Jr.s 1963 public letter masterpiece, Letter from a Birmingham Jail, the lifelong Methodist stalwart ran a publishing house associated with the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. One of Harmons projects during that time was the publication of a book that became a central influence on the thought of King and is now considered a sort of early classic of black liberation theology: Howard Thurmans Jesus and the Disinherited, originally published in 1949. During the days of the Montgomery bus boycott, King reportedly carried around copies of Thurmans short but powerful text in his coat pocket.

Abingdon-Cokesbury Press had first rights of refusal on the book, and Thurman assumed the southern bias of the press would lessen or eliminate its interest in the manuscript. But, in one of the many ironies surrounding the publication of the text, that was not the case. The editor of the press, Nolan Bailey Harmon Jr., hailed from Meridian, Mississippi. He served for years as a circuit-riding minister, then journal editor, then bishop for southern Methodists. And, as is detailed in S. Jonathan Basss tremendous work of historical research, Harmon had a long history of racial paternalism. He immersed himself in versions of a Lost Cause theology extolling the virtues of Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee.

Most notably, Harmon was one of the eight southern moderate clergy men who fell under withering condemnation in Kings Letter, which actually declared southern moderates to be a greater enemy to racial progress than the Ku Klux Klansmen. Harmon had joined in a letter to King urging that civil rights protestors observe the principles of law and order and common sense. Harmon himself thought racial progress would come only after the slow, slow, slow processes of time. Thus, he was the perfect exemplar of the attitude King so memorably lacerated in the letterthe idea that, somehow, time would heal the wounds. As King responded, time was neutral and by itself would solve nothing.

But fifteen years earlier, Harmon was closely involved in marking up the first draft of Thurmans manuscript for what became Jesus and the Disinherited. Thurman was not one to wait for the slow processes of time. During those years, in fact, he served as the pastor of the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples, an interracial congregation in San Francisco that might have been the worst nightmare for any southern segregationist, and probably uncomfortable for a southern white moderate like Harmon. But Harmon served effectively as an editor for Thurmans manuscript, demanding more changes of the proud African-American minister and intellectual than he was accustomed to accepting from others. Jesus and the Disinherited was Thurmans most succinct, and in many ways grittiest, expression of many of the fundamental ideas he pursued throughout his career: that the meaning of Jesus could be found in his status as a poor disinherited Jew living under an oppressive Roman regime.

Harmons backstory is one of many ironies brought to mind in reading Basss indispensable text of southern religious history, Blessed Are the Peacemakers. Bass tells multiple stories here related to this central document in American religion. One involves the writing of the letter itself, a process that bears some, but only some, relationship to the mythology that quickly grew up around (and was deliberately fostered and promoted about) it. Like many of Martin Luther Kings triumphs, the success of the letter (and of the Birmingham campaign) depended on a fragile but essential combination of intuitive genius, incredible personal commitment and bravery, religious faith, and carefully orchestrated media manipulation to produce the desired effect.

The other storyor rather, collection of storiesdetailed here in a manner not duplicated or even approached anywhere else, is the history of the eight signatories to the white clergymens Good Friday statement, April 12, 1963. Written and published by the Methodists Nolan Harmon and Paul Hardin Jr., the Episcopalians Charles Colcock Jones Carpenter and George Murray, the Catholic Joseph Durick, the Jewish Milton Grafman, the Presbyterian Edward Ramage, and the Baptist Earl Stallings, the letter reflected a common sentiment of the times that the problems in Birmingham could be worked out through goodwill and negotiations, without the intervention of civil rights demonstrations. We agree rather with certain local negro leadership which has called for honest and open negotiations of racial issues in our area, they said. They feared the demonstrations were unwise and untimely.