2018 University of South Carolina

Published by the University of South Carolina Press

Columbia, South Carolina 29208

www.sc.edu/uscpress

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data can be found at http://catalog.loc.gov/.

ISBN 978-1-61117-864-7 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-61117-865-4 (ebook)

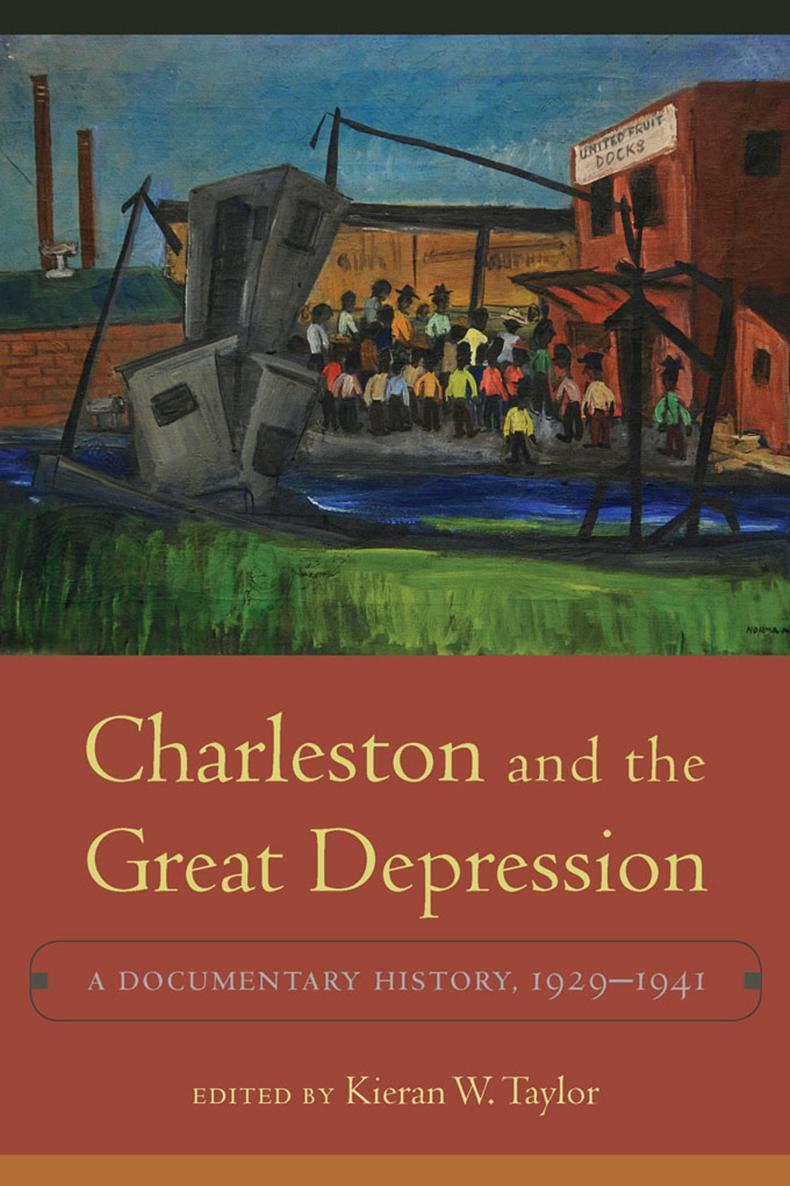

Front cover illustration: Norma Mazo, Payday, 1935

Acknowledgments

This volume is the product of a collaborative research project that began in two sections of Introduction to the Discipline of History, an undergraduate class that I taught at the Citadel in the fall of 2014. I designed the course assignments to provide students with the opportunity to work on a large, publishable historical research project. After selecting primary materials for the collection, I assigned each student one or two documents, which they transcribed, researched, and annotated. The course required both group work and intensive one-on-one tutorials, during which we discussed standard transcription practices, editorial principles, research methods, and historical writing. I wanted the students to learn the discipline of history through the practice of history. I chose Charleston and Great Depression as the project theme because of the lack of historical writing on the period and the easy accessibilty of local source material. I also did so as a political intervention. My idea was to expose my students to a period in U.S. history that would be both familiar and unfamiliar to them. The students have ideas about the Great Depression that are a part of our shared national memory. They may have even heard firsthand stories of the 1930s from grandparents or great-grandparents. Like their grandparents and great-grandparents, my students have lived through a period of tremendous economic upheaval and considerable hardshipthe recession of 20082009 and its aftermathand they continue to face an uncertain job market and troubling economic trends that include an unsustainable gap between the rich and poor. Unlike their elders, however, they live in a period of widespread cynicism regarding government and the political system. Despite their many differences and disagreements, the vast majority of Americans subscribed to Franklin D. Roosevelts New Deal. They believed in the idea that government power could and should be used to improve peoples lives. I wanted to immerse my students in those more hopeful politics of the 1930s, a period in which Americans believed that politics should serve as an expression of the commonweal. How successful was my intervention? I do not know. It will be up to them to draw their own lessons from the Great Depression. I do know that the following women and men were excellent colleagueshard working, cooperative, and patient: Preston Abernathy, Ryan Abts, Tjark Aldeborgh, Michael Bell, Sean Brennan, William Brown, Sophie-Leigh Clark, Gregory Copplin, William Denman, Taylor Evans, RaShaud Graham, Logan Higaki, Thomas Jordan, Anthony Kniffin, Dillon Luedtke, Derek Massey, William Maxwell, Joshua Park, Frost Parker, Monica Paulk, John Pferdmenges, Colin Poppert, William Richardson, Landon Rohrer, Matthew Russell, Joshua Scaife, Megan Sowell, Daniel Trimnal, Joseph Vicci, Maureen Wilkinson, and Justine Zukowski. They all made significant editorial contributions to this volume.

Additionally, several graduate assistants verified transcriptions and followed up on many vague research leads that I provided them. They include Orianna Baham, John Clark, and Matt Carroll, who also enlisted the help of Amanda Graves Carroll. The smart and unflappable Ariel Washington was a model research assistant in the earliest phases of this project. I look forward to working with her again when she finishes her doctoral studies in Chapel Hill.

The following Charleston-area archivists were very generous in helping me locate relevant documents, providing necessary publication permissions, and responding to my research queries: Barrye Brown, Karen Emmons, Mary Jo Fairchild, David Goble, Kathleen Gray, Harlan Greene, Susan Hoffius, Meg Moughan, Elaine Robbins, Dale Rosengarten, Rebecca Schultz, Aaron Spelbring, and Deborah Turkewitz. We are spoiled to have a group of such knowledgeable and generous archivists here in Charleston. I also relied on the generosity of a number of historians in producing the introduction and annotations. On short notice, Bruce Baker, Stephen Hoffius, and Bo Moore offered valuable feedback on the introduction; and several other scholars drew on their expertise to offer guidance on various aspects of the manuscript. They include Tenisha Armstrong, Clarissa Brown, Rachel Donaldson, Erik Gellman, S. T. Joshi, Keith Knapp, Alex Moore, and John Sacca. The Citadel Foundation has provided excellent research support for this project and all of my research efforts, as has the Department of History.

Finally, personal thanks are in order to colleagues and friends who have overlooked my neglect of various professional and community-organizing responsibilities, especially in this last month or two of manuscript preparation. They include Marina Lopez, Christine Nelson, and Leonard Riley Jr.. Kimberly Clifton has been similarly tolerant on the home front, and for her patience, love, and support I will always be grateful.

Editorial Principles and Practices

Each document selected for publication in this volume provides a window into events and themes related to life in Charleston in the 1930s. Their inclusion is intended to spotlight the rich body of primary source material available to scholars of the regions history and to encourage further study in related subject areas. The documents include correspondence, speech transcripts, photographs, artwork, oral histories, organizational reports, diaries, newspaper items, magazine articles, and court documents. Many of the themes they address will be familiar to students of the Great Depression, including stories of human suffering, public health challenges, and various New Deal initiatives. But there is much here that will be less familiar, even to specialists in local history.

A title, date, and place of origin introduce each document. The existing titles of documents are used when available and are designated by quotation marks or italics. For documents that are untitled in their original form, I have created descriptive titles that reflect their content (for example, Burnet R. Maybank to John L. M. Irby). When the date or place was not specified on the document but has been determined through research, it is enclosed in square brackets. In some instances, a date range is given when a specific date was not available.

The annotations are intended to enhance the readers understanding of the documents. Headnotes provide context for each documents creation; a brief summary may also be included for longer documents. Headnotes and editorial endnotes identify individuals, organizations, events, literary quotations, and other references in the source document. The annotations may also refer the reader to relevant correspondence and other related documents. The source note at the end of each document provides information regarding the characteristics of the original document as well as its provenance. The manuscript or archival collection from which each original document was obtained is also listed.