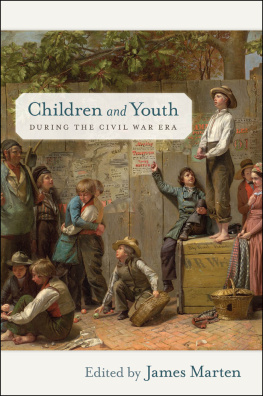

Children and Youth during the Civil War Era

CHILDREN AND YOUTH IN AMERICA

General Editor: James Marten

Children in Colonial America

Edited by James Marten

Children and Youth in a New Nation

Edited by James Marten

Children and Youth during the Civil War Era

Edited by James Marten

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York and London

www.nyupress.org

2012 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing.

Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs

that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Children and youth during the Civil War era / [edited by] James Marten.

p. cm.

ISBN 9780814796078 (hardback)

ISBN 9780814796085 (pb)

ISBN 9780814763391 (ebook)

1. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Children.

2. Children and warUnited StatesHistory19th century.

3. Children and warConfederate States of America.

I. Marten, James Alan.

E540.C47C45 2012

973.7083dc23 2011028196

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

c 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

p 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Acknowledgments

My greatest thanks go to Steve Mintz for his kind foreword and to the authors for their timely responses to what must have seemed an endless string of demands, suggestions, and queries. The anonymous readers provided helpful comments that strengthened the individual essays as well as the editors introductions. The Children and Youth in America series has found a friendly home at NYU Press, thanks to Eric Zinner and the rest of the staff, especially Ciara McLaughlin and Despina Papazoglou Gimbel, and Susan Ecklund, who copyedited the manuscript.

The authors and I also thank the following repositories for granting permission to publish texts and images from their collections: the American Antiquarian Society for The Early Development of Southern Chivalry; the Atlanta History Center for excerpts from the Carrie Berry Diary; the Dartmouth College Library for A Few Words to the Trustees; the Library Company of Philadelphia for Maltreatment of Inmates of the Schools for Soldiers Orphans; the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division for The Four Seasons of Life: Youth; the Missouri History Museum for the ambrotype of H. E. Hayward and Slave Nurse Louisa; the New Jersey Historical Society for excerpts and images from the Newark High School Atheneum; and the State Archives of Florida for the photograph of Magby Peterson and His Nanny.

Foreword

STEVEN MINTZ

Unlike other books on the Civil War era that focus on key events, epic political controversies, and great menpresidents, members of Congress, and generalsthis volume places another cast of characters center stage: children and youth. At the time of the Civil War, fully half of the nations population was under sixteen, and the young, like their elders, found themselves caught up in the major developments of the era: the growth of sectionalism, the moral debates over slavery, and the transformation of the sectional struggle into the first modern total war. More than mere bystanders or victims, a surprising number of young people participated directly in the eras upheavals and carried the impact of the Civil War into the succeeding decades. Viewing this era through childrens ordinary eyes yields extraordinary insights.

Children and youth were anything but bit players in the periods dramas. Like their parents, young people fashioned their own opinions about slavery and the sectional conflict in the decades preceding the Civil War. Many became highly politicized before or during the war, arguing the issues of the day in debating societies, joining juvenile affiliates of antislavery organizations, and publishing their own newspapers. In an essay on New England college students, Kanisorn Wongsrichanalai shows the extent to which these young men developed an intense anti-Southern ideology, expressing profound contempt for white Southerners and Southern society.

Meanwhile, images of childhood colored the political debates preceding the Civil War. The abolitionists single most devastating critique of slavery lay in its impact on children: how the institution separated families and undermined parents ability to protect their children and stripped the young of a childhoodmaking the early years a time of harsh labor and cruel punishment rather than a time of play and wonder. Indeed, as Rebecca de Schweinitz demonstrates, the slavery controversy led many Northern adults to think about childhood in a new way, as a stage of life that should, ideally, be free of work responsibilities and devoted to schooling and play. In the South, in contrast, as Elizabeth Kuebler-Wolf shows, apologists for slavery presented highly idealized portraits of the lives of children in bondage and of the supposedly close relations between black and white children in their defenses of the slave system.

During the Civil War, some young people found themselves on the front lines. A surprising number of young people participated in the war, as drummer boys and boy soldiers. Perhaps 5 percent of the soldiers were under the age of eighteen. Yet far from the battlefield, the war also made itself felt. It proved impossible to insulate children and youth from the wars impact. Boys played soldiers, and girls, nurses. The young also participated in relief work and in fund-raising sanitary fairs. Schoolbooks, childrens literature, parades, panoramas, and fairs made the war a part of everyday life. As Paul Ringel reveals, the popular childrens magazine Youths Companion, which had scrupulously avoided sectional tensions before the war, began to feature incidents from the war and included stories emphasizing the themes of patriotism, duty, and sacrifice.

Children were the Civil Wars most vulnerable victims. Noncombatants saw horrific acts of violence. War disrupted food supplies, resulting in hunger and disease, and displaced and separated families. Many young people became refugees, including the thousands of slave children who made up the majority of the contrabands who fled plantations to find refuge behind Union lines. Many experienced anxiety, fear, family separation, and loss. Sean A. Scotts contribution to this volume explains how children coped with wartime death, finding consolation from a religion that emphasized the reunion of family members in heaven. Even courtship became politicized. As Victoria E. Ott demonstrates, during the Civil War many young white Southern women, eager to prove their loyalty to the Confederate cause, denounced men who failed to serve in the military and rebuffed advances from Union soldiers.