NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2019 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

ISBN : 978-1-4798-9499-4 (hardback)

ISBN : 978-1-4798-0811-3 (paperback)

For Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data, please contact the Library of Congress.

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

This project is dedicated to Ena A. Austin and Pearl Shelby Sharpe, two everyday women who inspired and encouraged me to tell (historicized) stories. I miss you and hope you are proud of this. And to Nasia, Ari, and Jordan who, early on, created in me an appreciation for the intellectual capacity of young people.

There is a dearth of traditional records for the thoughts and experiences of black poor and working-class folks and this has informed their presence, their absence, and their misrepresentation in the historical record. As historian Cheryl Hicks notes, ordinary people rarely [leave] personal documents attesting to their lives and [are] often under-represented in organizations and the press. This, of course, is even truer in the study of marginalized poor and working-class (urban) African American youth, who are simultaneously seen as at risk and prone to criminality and deviance because of the ghettos influences.

But this historical manifestation, or lack thereof, is not solely a result of the scarcity of sources. Even in the revisionist period of the late twentieth century, scholars generally avoided the daily lives, the consciousness, and the intellectual production of common folks in an effort to render a portrait of racial progress. Black intellectual histories have spotlighted the ideological framings of black elites, many of whom had very conflicted feelings and ideas about black folk.

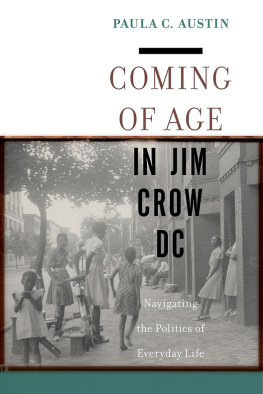

Coming of Age in Jim Crow DC offers alternative, complicated narratives of black young people who lived in Washington, DC, during the interwar period. Some were native Washingtonians, some were recent newcomers from parts south and east. Most lived in tight, overcrowded, and generally impoverished conditions. All were coming of age in the segregated US capital. This project listens to black poor and working-class young people as thinkers, theorists, critics, and commentators as they reckoned with, reconciled, and even played with material and rhetorical lines of demarcation set about them both as young people controlled by their parents and other adults and as African Americans in the racially, spatially, economically, and politically restricted city that was also the United States emblem of equality.

The racial protocol for how black lives could be represented in scholarship reduce[d] African American experiences to racial politics [and] racial struggle; it paid little attention to private life, individual subjectivity, and interiority. It created a two-dimensionality and a homogeneity of black life. And as both historian Anastasia Curwood and literary scholar Kevin Quashie note, hiding black interiority from public view can lead to the belief that Black people lack interior lives altogether. Coming of Age in Jim Crow DC uses sociological investigations and community and individual interviews that were conducted in the late Progressive and interwar era to highlight the inner and everyday lives, the self-aware and self-reflective analytic frameworks cultivated and articulated by poor and working-class black young people in an urban and social history of Jim Crow Washington, DC.

Social science literature of this era has generally portrayed marginalized black folks as socially and culturally homogeneous in the aggregatewhether represented as in need of rehabilitation or as proletarianized. These studies have rightfully been criticized for reinscribing conventional frameworks of racial and class identities and for reifying social formations steeped in middle-class norms and values. But because of their intrusiveness into communities and peoples personal lives, these materials also give us some access to inner life, to the life of the mind.

The meaning and force of Claras words inspire and animate this book.

Here I borrow the concepts of interiority and infra-ordinary from poets and literary theorists. Interiority refers to a consciousness of depth and space within; a sensibility; human inwardness;

By foregrounding interiority and the infra-ordinary, the narratives at the center of this book provide a different understanding of black urban life in the early twentieth century, a period most scholars identify as both the Great Migration and inclusive of the New Negro Movement and the origins of black ghetto formation. We have come to see urbanization But what comes through in these narratives are the ways in which black young working-class and poor people were expertly aware of the economic, spatial, social, and political limitations imposed by the District of Columbias racially segregationist policies and customs, and their critiques of the juxtaposition of those limitations with the emblematic meanings of the nations capital.

Young peoples answers to social science questions make clear the cultivation and mobilization of their own analytic categories and frames, even for the youngest subject. Sometimes these conceptual frames were in tune with and sometimes they diverged from mainstream middle-class mores as promoted by black and white reformers alike. Individuals articulated spatial, racial, class, and gender identities, complex social relations, and a deep consciousness of selfhood with which they negotiated the contradictions of living in the urbanizing and racially segregated US capital. These musings map onto the history of Washington, DC, just as DC planners worked to create a landscape to establish the city on a global stage, and just as the federal governments physical presence invaded historically black and poor spaces.

DC histories have addressed both its racial segregationist past and the origins of its black urban ghettoes. This includes the early Federal Writers Project 1937 DC guidebook and its 1942 edition.

Coming of Age in Jim Crow DC is indebted to three publications that take note of DCs poor and working-class African Americans, and address the juxtaposition of DCs imagined and experienced landscapes. DC is a national space, a celebrated and for some a sacred space of commemoration. And it was and continues to be a contested space, a space of confrontation and politics.

Two other publications on the history of Washington, DC, specifically center the lives and experiences of black poor and working people. The first, James Borcherts Alley Life in Washington, traced the survival and continuity of southern rural folkways within DCs black and poor alley communities. Borchert used materials produced by social scientists