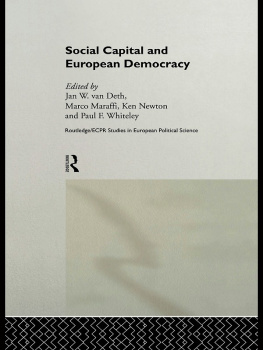

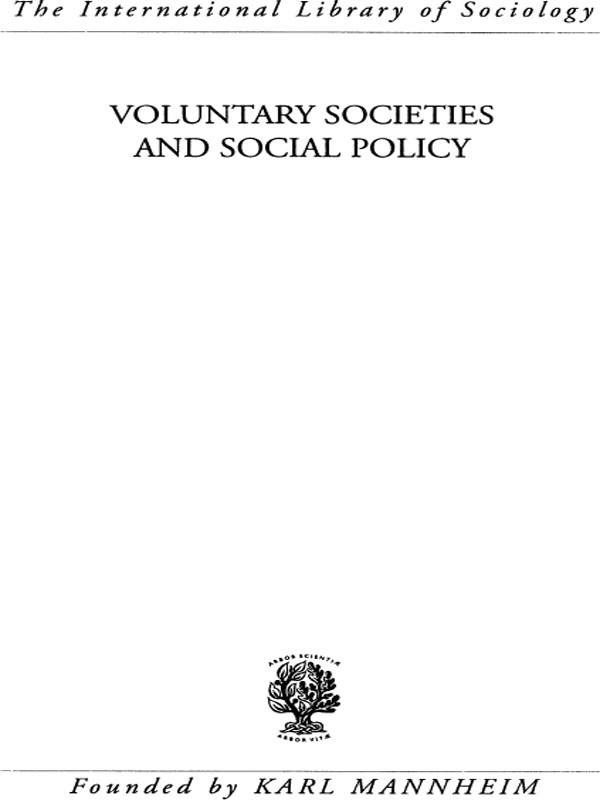

First published in 1957 by

Routledge

Reprinted 1998, 1999 (Twice) by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, 0X14 4RN

Transferred to Digital Printing 2007

1957 Madeline Rooff

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

The publishers have made every effort to contact authors/copyright holders of the works reprinted in The International Library of Sociology. This has not been possible in every case, however, and we would welcome correspondence from those individuals/companies we have been unable to trace.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

Voluntary Societies and Social Policy

ISBN 0-415-17728-6

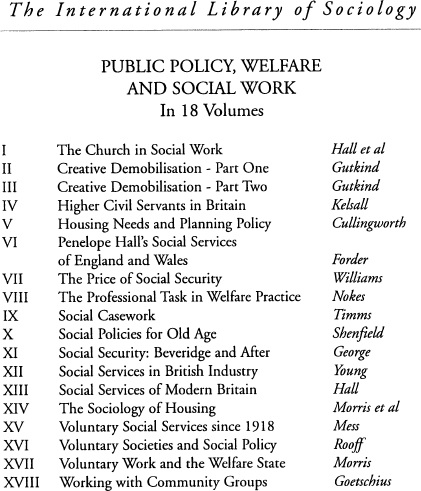

Public Policy, Welfare and Social Work: 18 Volumes

ISBN 0-415-17831-2

The International Library of Sociology: 274 Volumes

ISBN 0-415-17838-X

ISBN 978-1-136-26392-7 (ePub)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original may be apparent

TABLES

I am greatly indebted to the many voluntary and statutory bodies without whose help this study would have been impossible. I should like in particular to thank the senior officers of voluntary societies who not only lent reports and journals and discussed problems with me, but who also read the relevant sections of the manuscript: they include members of the staff of the National Association for Mental Health, the Royal National Institute for the Blind, the National Association for Maternal and Child Welfare, the Family Welfare Association and the National Council of Social Service. The secretaries of the Mental After-Care Association, of the National Baby Welfare Council and of the Southern Regional Association for the Blind also gave most helpful interviews and lent documentary material. I received valuable suggestions from officers of the Ministry of Health in the Departments of Maternity and Child Welfare, Mental Health and the Welfare of the Blind, who read parts of the manuscript and discussed questions arising, and from officers in the Department of the Comptroller of the London County Council who supplied statistics not generally available and took great trouble in checking figures submitted to them.

I may perhaps be allowed to mention two distinguished public servants by name since they are both retired: Dr. McCleary read the section on maternity and child welfare, and Miss Bramhall that on the welfare of the blind. Their friendly criticism was much appreciated.

I should like also to thank my colleagues at Bedford College, especially Dr. Wootton, who, with the help of a small research grant, started me off on this enterprise; Professor Lady Williams who took a continued interest in the progress of the study and encouraged me when circumstances seemed adverse; Dr. Pinchbeck who most kindly read the script in its later stages; Mrs. Jefferys who helped to prepare the tables and diagram; and the library staff for their co-operation at all times.

Finally I should like to record my gratitude to my friend, Miss Dorothy Trollope, who not only read the first drafts of the manuscript, but also volunteered to correct the proofs.

I must add that, although I received much valuable criticism and advice, those I have mentioned are in no way responsible for the use I have made of the material.

MADELINE ROOFF

Bedford College,

Regents Park, London, N.W.I.

September 1956

My main purpose is to throw some light on the changing role of voluntary organisations and their relation with statutory bodies in the provision of the British social services.

The great experiments in social welfare in the mid-20th century have stimulated interest in the social services. Overseas visitors are constantly enquiring 'how things began', while sociologists are aware of the need for more detailed research into origins and development if the problems of to-day are to be fully understood.

This country has built up a unique partnership of voluntary and statutory action but, so far, there has been little investigation into the nature of the relationship.1 An Official History1 may acclaim voluntary action as * characteristic of the British Social services', and social legislation may embody the principle of co-operation between statutory and voluntary agencies, but there is still some uncertainty about the function of voluntary organisations in a community which has achieved a reasonable measure of social security and welfare.

Co-operation and co-ordination have become vital issues in the complex society of to-day. The achievement of satisfactory relations between individuals and groups is one of the outstanding problems of social administration. It is not always easy to understand the varying attitudes of local authorities towards public and private enterprise in the provision of the social services. The rapidity with which changes have occurred in social policy and social structure have made it difficult to see the pattern as a whole. It is clear, however, that the influence of the past is still strong. For this reason special attention is paid, in this study, to origins and development, in the attempt to analyse the causes of friction and the conditions which make for co-operation, and to discover the reasons for persistence and change.

1 There have been several general studies of voluntary action, e.g. those by H. Mess, and by the Nuffield Foundation, and later, that by Lord Beveridge. The official report on Law and Practice Relating to Charitable Trusts has thrown light on important aspects of the question.

As my study was nearing completion an enquiry was undertaken by Mr. Mencher, a Fulbright scholar, into the relationship between voluntary and statutory agencies in a few selected areas. This has now been published as a pamphlet by the F.W.A. When my manuscript was completed a forthcoming publication by Young and Ashton on British Social Work in the 19th Century was announced.

2 See the official History of the Second World War: Civilian Health and Medical Services.

It has been decided to select a few services for intensive study, concentrating, for the most part, upon Mental Health, Maternity and Child Welfare, and the Welfare of the Blind. No attempt has been made to cover the whole range of services within each field: for the purpose of illustration, the main emphasis has been upon 'community care' as distinct from residential care, although it is recognised that voluntary organisations have done, and are still doing, valuable work in the provision of homes, hostels and other institutions. Even though most hospitals and some convalescent homes were taken over as a statutory service after the introduction of the National Health Service, voluntary bodies such as the British Red Cross Society and the W.V.S. continued to play a welcome part in the provision of many new welfare services, giving what officials liked to call the 'personal touch'.