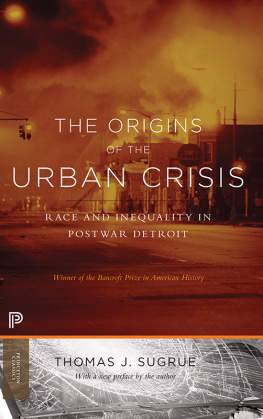

Death of a Suburban Dream

POLITICS AND CULTURE IN MODERN AMERICA

Series Editors: Margot Canaday, Glenda Gilmore,

Michael Kazin, and Thomas J. Sugrue

Volumes in the series narrate and analyze political and social change in the broadest dimensions from 1865 to the present, including ideas about the ways people have sought and wielded power in the public sphere and the language and institutions of politics at all levelslocal, national, and transnational. The series is motivated by a desire to reverse the fragmentation of modern U.S. history and to encourage synthetic perspectives on social movements and the state, on gender, race, and labor, and on intellectual history and popular culture.

Copyright 2014 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A Cataloging-in-Publication Record is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-8122-4598-1

Introduction

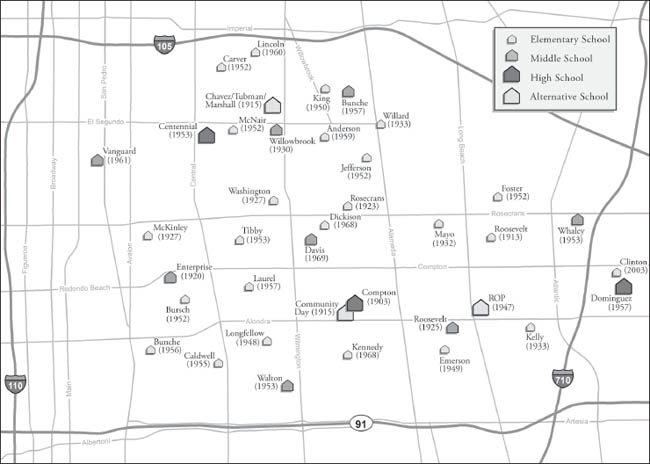

Marlene Romero watched as her son struggled in school. In his five years at McKinley Elementary in Compton, California, her child had worked hard to master basic math but, according to Romero, he had received no extra help from his teachers. In fact, by her count, her son has had just one effective teacher in his five years at McKinley.

The groups efforts bore fruit. In December 2010, 61 percent of the parents at McKinley voted no confidence in their neighborhood elementary school, activating Californias new parent trigger law. According to the state statute, when a majority of parents signed a petition to define their school as failing, the district had three options: replace staff or teachers, close the school, or give the school over to an independent organization to establish a charter school. In this case, the parents of 275 of McKinleys 442 students demanded a charter school. It became the first use of such a law in the United States.

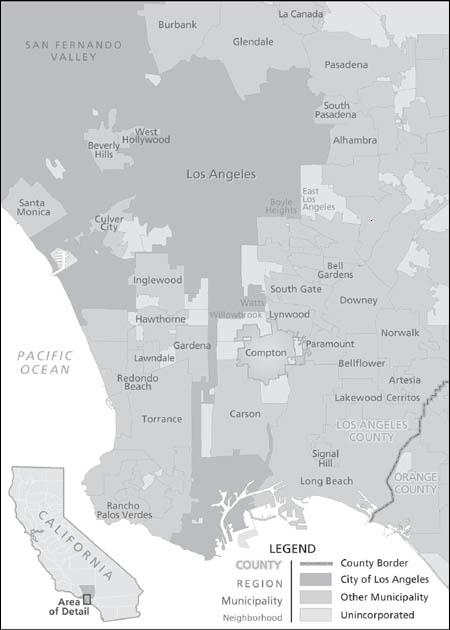

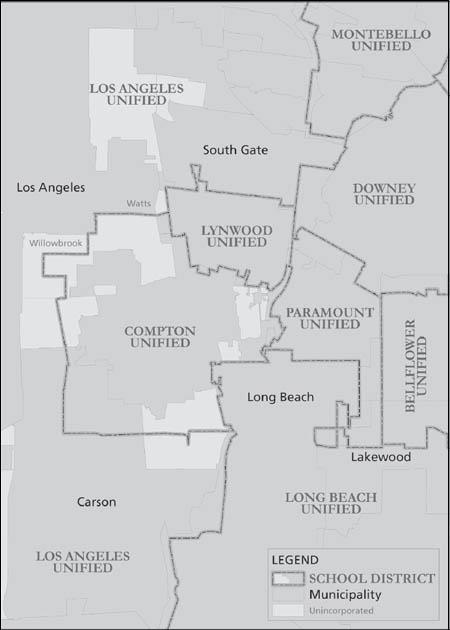

It is not surprising that this battle over school failure happened in Compton, a Los Angeles area suburb where public schools have a particularly abysmal history. Indeed, in many ways the districts schools have come to symbolize the larger national problem of educational bankruptcy. In 1993, seventeen years before the legislature enacted the trigger law, the district became the first in California to be taken over by the state for both financial and academic failure. After decades of neglect and corruption, the Compton Unified School District was left with dilapidated school plants and enormous debt. It had the worst test scores in the state and the lowest paid teachers in Los Angeles County.problems, and in many ways because of them, Compton could not attract the best teachers, retain many of the strong teachers it had, or replace those that left in any consistent manner.

Comptons debt became so overwhelming that, by March 1993, the district could neither pay its teachers for the rest of the school year nor afford to open the schools in the fall. Out of sheer desperation, the district requested a $20 million emergency loan from the state, opening the door to a takeover by the state government. California agreed to lend the district $10.5 million and took Compton Unified into receivership, seizing the powers of the districts elected board of trustees and relegating it to an advisory role. A few months later the state added to its charge improving the academic performance of Compton Unified students.

The presence of a state administrator in Compton prompted debate among local residents over who should hold power, as well as what constituted academic performance and what it meant to elevate it. Race played a central role in the debate over the takeover. Some residents deemed this involvement racist, claiming that the state seized power only because African Americans controlled the district of approximately 28,000 pupils, almost all of whom were black or Latino. Others in Comptons black community claimed state officials had ignored the corruption, neglect, and academic failure in Compton precisely because it was a minority-run district. Surely, they argued, if Compton were a white district, the state would have intervened earlier. The state takeover indeed highlighted a deep connection between racial discrimination and educational opportunity. Local district officials did not regain full control until eight years later, in December 2001, only to have residents request state intervention at McKinley again in 2010.

I first encountered Compton during the state receivership. On graduating from college in the mid-1990s, I joined Teach For America and was hired to teach middle school students in Compton Unified. During my time as a teacher in the district I came to know the students, parents, and educators. They not only opened a classroom to me but also entrusted me with their concerns about and desires for their children, schools, and community. Together we shared many hopes and frustrationsand there was much about which to be frustrated. Even under state control, problems still pervaded every aspect of the district. I felt this daily. Each of my classes had forty pre-teens, all of whom scored below the 35th percentile on statewide standardized tests and most of whom could neither read an early elementary school primer nor write a complete sentence. Along with these academic challenges, my students and I had to contend with a run-down physical plant that inhibited learning. The students sat in dilapidated furniture discarded by a private school. Our classroom ceiling had a gaping hole. On clear days we could see the sky, and on rainy days water streamed into the room.

Many of the questions that first arose for me as an educator in Compton have remained with me as a scholar. What caused the school crisis in Compton? And what was the relationship between the problems I witnessed within the schoolhouse walls, the challenges facing the community, and the problems in society at large? The answers lie at the heart of this book and call into question basic assumptions that many Americans hold about the urban-suburban divide, public school problems, and their potential solutions. Comptons school crisis was not created solely within schoolhouse walls; it was not simply about bad teachers, uncaring principals, or neglected students, though these were certainly part of it. Rather, the crisis evolved over time from the complex, intertwined relationships among racial inequality, economic opportunity, community culture, and educational policy. The educational crisis in Compton, as in so many places across the country, has deep and far-ranging historical roots, and while shifting control of McKinley Elementary School may help Marlene Romeros son with his math, individual school reform will not lead to sustained improvement. Instead, anyone concerned with the plight of American public schools must take a broader and longer view of the structural causes of the problem and use that history to make informed decisions about the present and the future.