This book is dedicated to the memory of the late

Fr Walter Forde, Castlebridge, County Wexford,

chairman of the Byrne-Perry Summer School

held annually in Gorey, for which these

papers were initially produced.

Conor McNamara is the 1916 Scholar in Residence at Moore Institute, NUI Galway, for 2015/17. His books include The Easter Rebellion 1916: A New Illustrated History (2015) and The West of Ireland in the Nineteenth Century: New Perspectives (2011).

Pdraig Yeates is a member of the 1913 Committee. He is a journalist, trade union activist and author whose books include Lockout: Dublin 1913 (2010), A City in Wartime: Dublin 19141918 (2011), A City in Turmoil: Dublin 19191921 (2012) and A City in Civil War: Dublin 19211924 (2015). He previously edited the Irish People and worked for The Irish Times as Community Affairs and as Industry and Employment Correspondent.

The

Dublin

Lockout, 1913

New Perspectives on Class War & its Legacy

Conor McNamara

& Pdraig Yeates

First published in 2017 by

Irish Academic Press

10 Georges Street

Newbridge

Co. Kildare

Ireland

www.iap.ie

2017, Conor McNamara & Pdraig Yeates; individual contributors

9781911024781 (paper)

9781911024798 (cloth)

9781911024811 (Kindle)

9781911024828 (epub)

9781911024804 (PDF)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

An entry can be found on request

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

An entry can be found on request

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved

alone, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or

introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any

means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise)

without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the

above publisher of this book.

Interior design by www.jminfotechindia.com

Typeset in Adobe Caslon Pro 11/14 pt

Cover design by www.phoenix-graphicdesign.com

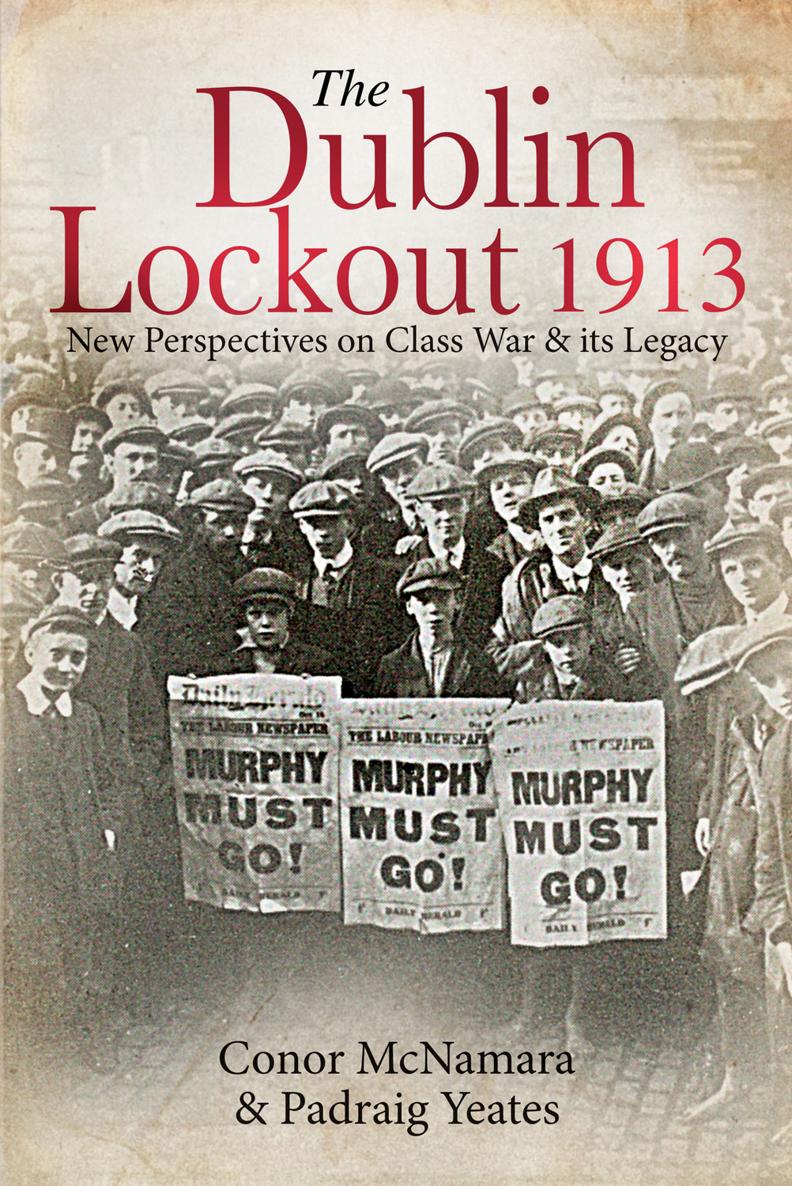

Cover/jacket front/back:

Murphy Must Go! (Image Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland)

Contents

Acknowledgements

T he authors would like to thank the organisers of the Byrne-Perry Summer School, particularly Patrick Brown and Eileen OLoughlin, for their steadfast endeavours. Sheila Fitzpatrick, Sen Mythen and Hazel Percival were central to the running of the conference.

This publication would not have been possible without the generous support of the Diocese of Ferns and SIPTU. We are grateful to Bishop Brennan for providing a fitting preface in memory of the late Fr Forde and to SIPTU General Secretary Joe OFlynn for his introduction on the continuing relevance of the Lockout legacy.

We would like to thanks all of the team at Irish Academic Press whose professionalism has been most appreciated, in particular, Conor Graham and Fiona Dunne.

We would also like to acknowledge the support of Mary Harris and John Cunningham at the History Department and Dan Carey, Moore Institute, NUI Galway; Maire Kennedy and Enda Leaney for putting the invaluable resources of the Dublin City Library and Archive at our disposal; and Eibhlin Colgan for access to the Guinness Archive, Diageo Archives magnificent photographic section.

We are deeply grateful to the contributors for their professionalism, enthusiasm and perseverance.

Foreword

by Joe OFlynn, General Secretary, SIPTU

T he 1913 Lockout continues to resonate with everyone interested in Irish history and with the development of modern Ireland. The strike by Dublin tramway workers for better pay that began on 26 August that year quickly escalated into a major political crisis after Bloody Sunday, when hundreds of people were batoned by the Dublin Metropolitan Police and Royal Irish Constabulary five days later. It developed into a much broader struggle that embraced not just the right of workers to collectively bargain with their employer and seek union recognition, but battles over the rights to freedom of assembly, free speech, gender equality, access to decent and affordable housing, and even the right of parents to decide how their children were educated. It also raised questions about what it meant to be Irish and who could be included, and excluded, from society. Over one hundred years on these issues are still of vital concern today. They go to the very essence of what it is to be a citizen, or a denizen on this island, north and south.

Then as now there were powerful vested interests that defended the status quo and questioned the legitimacy of those who challenged it, such as Jim Larkin and James Connolly, children of the Irish diaspora who came in their very different ways to epitomise the hopes of those who sought social justice, and radical political and economic change. Many of those who aligned with them in that fight, people as diverse as Dr Kathleen Lynn, Sean OCasey, Francis and Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, Tom Clarke and Countess Markievicz, either did not survive the Irish revolution or were marginalised in its counter revolutionary aftermath.

And yet some of the revolutionary ideas that emerged during the 1913 Lockout survived in the 1916 Proclamation and the Democratic Programme of the First Dil, ensuring the survival of these subversive principles at the very heart of the modern states constitution; even though the Free State that emerged in 1922 was much closer to the claustrophobically parochial vision of the Home Rule movement, mirrored by its Unionist counterpart in Northern Ireland. The course of the 1913 Lockout is therefore of concern to everyone, not just trade unionists. The fact that many of the rights sought then are still denied affects us all. Notwithstanding recent legislation, the right to full collective bargaining, which is the most effective means of redistributing wealth after taxation in a capitalist society, remains an objective we must constantly strive to achieve, particularly on behalf of vulnerable workers in low-paid and precarious employment. When this right is eroded, or denied, the certainty of inequality increases. Erosion of incomes, in turn, affects long-term life choices, such as the possibility of further education and career development for our children, and limit the aspirations of the general working population, as well as causing immediate falls in living standards.

The richer those at the top of society become the greater their capacity to manipulate the world to suit their agendas. The individualisation and commercialisation of peoples rights are not just imperatives of the market. They pose fundamental challenges to the social solidarity values that manifested themselves when the trade union movement emerged as a force to be reckoned with in 1913. If the dominance of unfettered market forces is not constantly challenged they will continue to promote the agendas of a wealthy elite, who pose a serious threat to democracy itself as they find it easier to manipulate a fragmented society than one underpinned by mass democratic movements acting collectively to defend peoples rights. Without such movements society falls easy prey to fear and the manipulation of its purveyors, whatever guise they assume, to stoke hate and division in pursuit of their agendas.