T hey called him Old Man Eloquent, but he was more than that, more than eloquent; he was resolute, canny, cantankerous. And though he liked to quote the Bible and Shakespeare and to frame an irrefutable argument, he could also be eloquently brusque. In fact, he had just uttered one unwavering word that day in the House. No , he had said, and no summarized how John Quincy Adams had spent his long lifeand where, in a sense, his country was heading: to a series of negatives, for good and for ill, that brooked no compromise or conversation.

No: No is the wildest word we consign to the language, as Emily Dickinson would say. The sixth president of the United States, eighty-one years old and a crusty member of the House of Representatives, had spoken loud and clear. It was the early afternoon on Monday, February 21, 1848. With his bald head fringed with a crown of white hair and a permanent scowl carved deep into his broad face, Adams struck his colleagues as the same as everhale, hearty, forthrightdespite of course the minor stroke he had suffered not too long ago. Yet he still could pursue an objective with unrelenting, single-minded focus. His grandson Henry Adams long remembered the summer day when he had been about six or seven and had rebelled against going to school until his grandfather, having emerged from his study, appeared at the top of the steps, descended the stairs, put on his hat, took the boys hand, and silently walked Henry the mile or so to the schoolhouse, whereupon Henry took his seat and his grandfather let go his hand and returned home, never having said a word.

A New England Puritan who loved scribbling in his colossal diary and arguing on behalf of his country, John Quincy Adams was never eclipsed by his own brass or mahogany, as another outspoken man, the radical Reverend Theodore Parker, would say. Known as wild or, at best, contentious in his views, according to Parker, he had encountered more political opposition than any other man in the nation. Persistently, he had battled for public education, improved transportation, civil rights, freedom of expressionand against the extension of slavery. Morally austere, without humor, glacially scrupulous, the bleak Old Man frequently reread his Cicero, and just the day before, he had twice attended church. In the evening he had read a sermon by the Reverend William Wilberforce, the British antislavery evangelical, for pleasure. It was about the passing of time.

The Old Mans habits had been unchanged for years. On Monday morning Adams woke early and rode by carriage from his home on F Street to the House of Representatives, where he represented Massachusetts, his cherished state. He adored Washington too, that rough and ready townthe city of magnificent intentions, Charles Dickens had called itand a work in progress to which Adams was devoted. Mud might clog the streets, if thats what you could call those unpaved passageways and lanes, pigs rooted for garbage, and summers were unbearable, what with the brackish swamps breeding disease and the city reeking with the bittersweet smell of horse manure. Neither the Washington Monument nor the Capitol was finished; they stood undressed, symbolic of the city and country that were to come. Public buildings that need but a public to complete, Dickens observed.

It was winter now, crisp and clear and not at all malarial or murky. At the House, Adams chatted with a few colleagues, nothing more. In the early afternoon, Speaker of the House Robert C. Winthrop (a friend) called the question of whether or not to suspend the rules in order to vote to award gold medals to various generals for their gallant action in what Adams, unequivocally, considered an unrighteous warthe war with Mexico. So Adams said no.

His face reddened. He had evidently muttered something else, too. Look to Mr. Adams! Look to Mr. Adams! several representatives cried. Adams grabbed for the corner of his desk and then slumped to the left of his chair. David Fisher of Ohio, seated next to him, caught Adams in his arms, and another quick-acting colleague ran for ice water and a compress.

Mr. Adams is dying! House members rushed forward to lift the elderly statesman to the space in front of the clerks table before several others brought in a sofa. Carefully lifted onto it, Adams was carried into the Rotunda. Winthrop adjourned the session.

As the members of the House dashed here and there, several senators, on hearing that Adams was stricken, thronged around the old man. So too did anxious visitors to the House, who had come to witness the days roll calls. They had not expected this. The thickening crowd prompted one of the House members to recommend that the sofa be removed to the East Portico, which might be better for the ex-president because a fresh east wind was blowing there. The physicians who were members of the House thought the place too damp. Winthrop suggested they go to the speakers room, where they would have more privacy. They bled Adams and applied mustard plasters, which seemed to give the poor man some relief even though his entire right side was paralyzed.

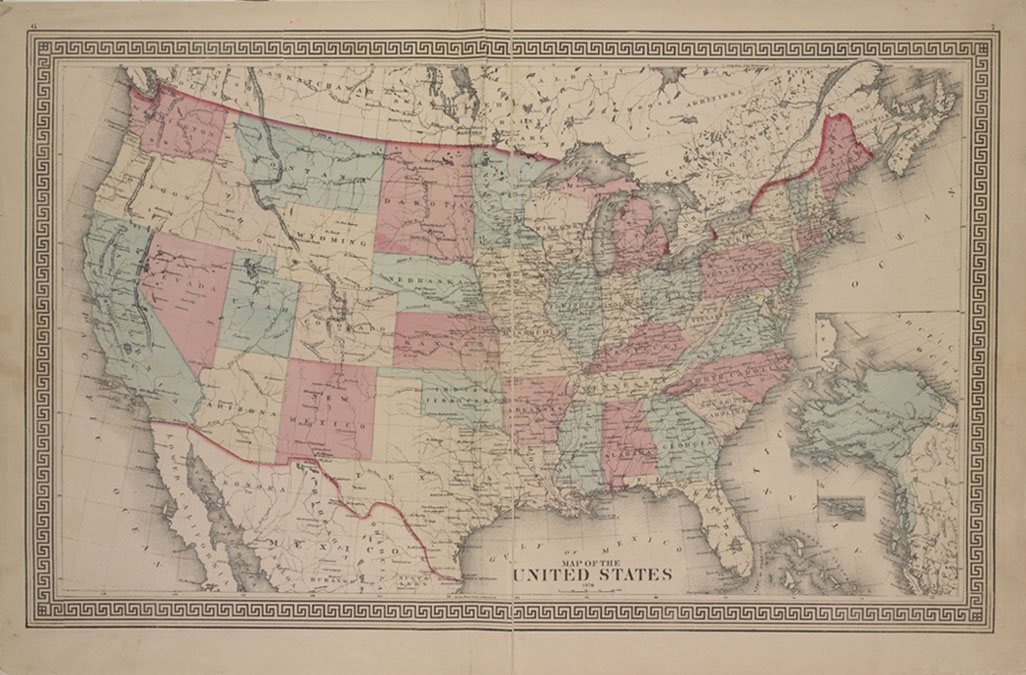

Adams asked for Henry Clay, who had been his secretary of state. Old Harry had also helped engineer what was known as the Missouri Compromise of 1820 (admitting Maine to the Union as a free state and Missouri as a slave state while pledging that the territory north of 36 degrees, 30 minutes latitude, would be forever free). Like Adams, Clay had run for president more than once and as recently as four years ago. He dashed out of the Senate chamber, tears streaming down his face.

This is the end of earth, Adams was heard to say. But I am composed.

Louisa Adams hurried in to see her husband, who by that time could not recognize her. Distraught, she left the room. Joshua Giddings, the passionate antislavery representative from Ohio, felt Adamss pulse and wiped the sweat from his brow.

All business in the hushed Capitol was suspended through the next day and the next day and the next. The celebration of Washingtons birthday was canceled. On the evening of February 23, 1848, after sixty years of public service, John Quincy died as he lay, fittingly, in the Capitol building. The electric telegraph madly tapped out the news.

N EWSPAPERS THROUGHOUT THE country chronicled the funerals every detail. The Stars and Stripes flew at half-mast while statesmen from the South as well as the North paid homage to the tough old contrarian as he lay in his glass-covered coffin in the House of Representatives. Thousands of people filed by, even those who had hated him during his long years as their public servant.

Had he died much earlier, Old Man Eloquent would not have been remembered with the outpourings of love and praise that accompanied his funeral train all the way to his ancestral home in Quincy, Massachusetts. For whatever his failures as president, whatever his want of judgment, whatever his intransigence, this was the man who had subsequently fought with all his might for the right of free speech when the House of Representatives passed a series of gag rules tabling all petitions or propositions related to slavery and its abolition. This was the man who had tried to establish relations with the independent state of Haiti and who, in 1841, when he was seventy-three, had successfully argued the Amistad case before the Supreme Court on behalf of freedom for a boatload of black men kidnapped from their African homes to be sold into slavery in Cuba. This was the man once called the Madman of Massachusetts whom irate representatives from the South had unsuccessfully tried to censure; this was the man who had hunkered down and won, over sectional dissensions, the right of slaves to petition Congress. This was the son of a president and a president himself, who, after he left the executive office, had broadened. He had possessed a capacity for growth, and he had loved a good fight, and his constituents loved him for that, all the more so after he was gone. When a motion was proposed in the House that a committee escort his body back to Massachusetts, a Southern representative objected. Whats the use of sending him home? he asked a fellow member. His people think more of his corpse than they do of any man living and will reelect it, and send it back. He put sulfuric acid, Ralph Waldo Emerson said, in his tea. And he bequeathed to his son Charles Francis Adams the words that he believed he and the country should live by: a stout heart and a clear conscience, and never despair.