WALT WHITMAN SPEAKS

Introduction and volume compilation copyright 2019 by

Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Library of America.

www.loa.org

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without

the permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief

quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Distributed to the trade in the United States

by Penguin Random House Inc. and in Canada

by Penguin Random House Canada Ltd.

eISBN 9781598536157

Contents

Introduction

BY BRENDA WINEAPPLE

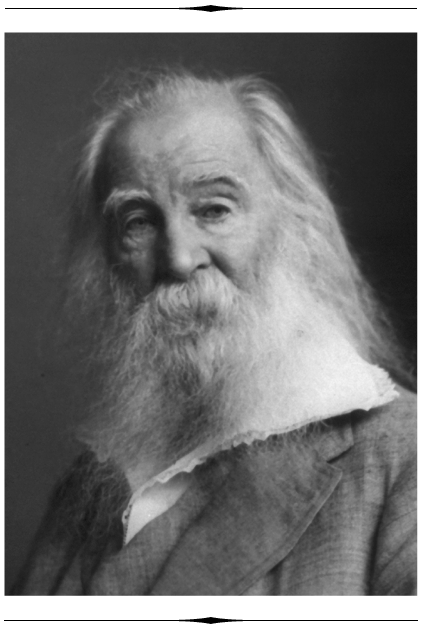

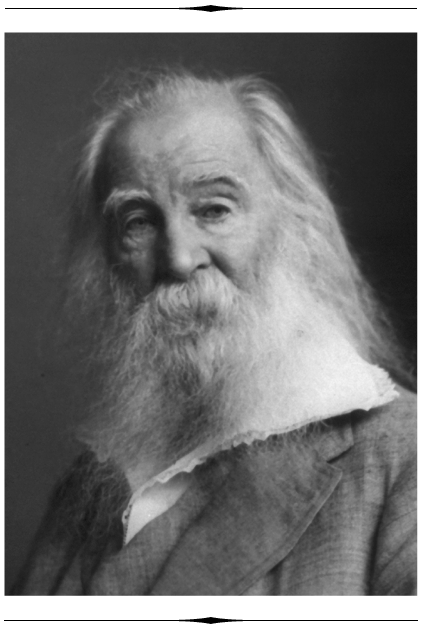

IN 1855 no one had yet heard anything like the raw, declamatory, and jubilant voice of the self-proclaimed American, one of the roughs, a kosmosthat is, Walt Whitman, who famously announced, I celebrate myself, / And what I assume you shall assume, / For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you. In his dazzling poetic debut, Leaves of Grass, published near the Fourth of July, Whitman was unequivocally declaring his own independence from poetic conventions and niceties. He didnt even include his name on the title page, although on the frontispiece there was a portrait of a bearded man, without cravat, his shirt open, with one hand on his hip, the other in his pocket, and his hat rakishly tipped back. Here was a poet of the people for the people, without pretension or pomp, who wrote in a verse form that captured everyday speech, both its fluency and its clank. The best writing, Whitman would say, has no lace on its sleeves.

And, now, in this volume, Whitman again speaks to us, this time from his home at 328 Mickle Street in Camden, New Jersey. I seem to be developing into a garrulous old mana talkera teller of stories, as he told his friend, Horace Traubel, the blue-eyed twenty-nine-year-old who was transcribing in shorthand most of what Whitman said to him during the last years of Whitmans life. By the time Whitman died in 1892, Traubel had accumulated about five thousand pages of these conversations, a monumental chronicle of Whitmans reflections, ruminations, analyses, and affirmations.

In many ways, Whitman and Traubel had been collaborating on a project begun in 1888. Although Whitman didnt know exactly what Traubel was jotting down, he understood that Traubel would write of their relationship one day, telling the trusted younger man, I want you to speak for me when I am dead. As Whitman further explained, you will be called on many a time in the future to bear witnessto quote these days, our work together, the talks, anxietiesthe victories, defeats. Whatever we do, we must let our history tell the truth: whatever becomes of us, tell the truth. For he didnt want to be mummified. Do not prettify me: include all the hells and damns, Whitman instructed. And when Traubel read back to Whitman some of what hed transcribed, as he sometimes did, Whitman replied with satisfaction, You do the thing just as I should wish it to be done. He had found his very own Boswell.

Whitman had first encountered Horace Traubel about fifteen years earlier, shortly after the poet had arrived in Camden in 1873. Traubel was carrying a large stack of library books, and Whitman had joked about a boy reading too much. They quickly formed a friendship and together they sat on the front stoop to discuss what theyd been reading, or theyd watch baseball games together on the Camden common. Initially, a number of people complained to Traubels mother that her son shouldnt associate with such an old lecher, but Traubel, who greatly admired the poet and his work, volunteered to run errands for an increasingly infirm Whitman.

Whitman had moved into his brothers home in Camden after suffering a stroke, and though he regained some strength and mobility, he continued staying with his brothers family, where his mother was also then living. After her death, when the rest of the Whitmans left Camden, the poet purchased a small, two-story row house on Mickle Street. By 1888, Traubel was stopping by every day, usually on his way home from nearby Philadelphia, where he worked as a bank clerk. As Whitmans unofficial amanuensis, he answered Whitmans letters, scoured Philadelphia for the kind of pens that Whitman liked, and was soon marshaling Whitmans friends together to help pay for his caregivers and nurses. Traubel arranged benefit lectures to defray their expense, and he organized the birthday dinners and iced champagne that delighted Whitman. Efficient and methodical, Traubel also acted as liaison to several editors when Whitman was preparing his volume, November Boughs. For the invaluable Traubel was proficient in matters of manuscript preparation, from printers and binders to publicity and promotion. Whitman entirely trusted him, and with Traubels able assistance, Whitman published such late volumes as a pocket edition of Leaves of Grass, a Complete Poems and Prose, the volume Good-bye My Fancy, and the deathbed edition of Leaves of Grass.

Traubel thus brought Whitman light, hope, encouragement, and love. I wonder whether you understand at all the functions you have come to fulfil here! that youre the only thing between me and death? Whitman exclaimed in 1889. That but for your readiness to abet me Id be stranded beyond rescue? As the biographer of Whitman, which is essentially what Traubel had become, he also sifted through the heap of manuscripts, letters, books, envelopes, magazines, and slips of paper strewn in apparently willy-nilly fashion all over Whitmans second-floor bedroom. I live here in a ruin of debrisa ruin of ruins, Whitman sheepishly admitted. If he proposed to burn or tear up a letter, Traubel intervened, often successfully, and whenever the young man asked for some document, Whitman handed it over without protest.

Their routine continued with rare exceptions, and by 1891, Traubel felt so close to the poet that he was married in Whitmans home. Utterly comfortable with one another, Traubel and Whitman could sit together in silence for long periods, but then Traubel might make a remark to encourage Whitman, trying nonetheless to not trespass and not to ply him too closely with questions necessary or unnecessary, as Traubel later said. But he pushed back against some of Whitmans biases, both men enjoying the give-and-take. For Traubel was a committed socialist, which Whitman decidedly was not. How much have you looked into the subject of the economic origin of things we call vices, evils, sins? Traubel gently needled his friend. Smiling, Whitman replied with good humor, You know how I shy at problems, duties, consciences: you seem to like to trip me with your pertinent impertinences.

In turn, Whitman would tease Traubel, promising him revelations that he never delivered, such as the secret Whitman described as the one big factor, entanglement (I may almost say tragedy) of my life about which I have not so far talked freely with you. Prodded, Whitman demurred. Some day the right day will comethen well have a big pow-wow about it, he temporized. The right day never came. There is something furtive in my nature, Whitman once told a friend, like an old hen. If Whitman did in fact reveal a secret, Traubel didnt record it, although he seems to have recorded everything faithfully and to have fulfilled his promise not to sanitize or to censor.