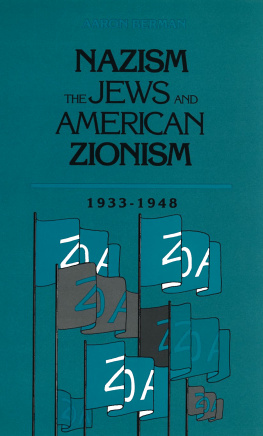

NAZISM

THE JEWS AND

AMERICAN

ZIONISM

1933-1948

AARON BERMAN

WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS DETROIT

Copyright 1990 by Wayne State University Press , Detroit , Michigan 48202. All material in this work, except as identified below, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/.

All material not licensed under a Creative Commons license is all rights reserved. Permission must be obtained from the copyright owner to use this material.

The publication of this volume in a freely accessible digital format has been made possible by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Mellon Foundation through their Humanities Open Book Program.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Berman, Aaron , 1952

Nazism, the Jews, and American Zionism, 19331948 / Aaron Berman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-8143-4404-0 (paperback); 978-0-8143-4403-3 (ebook)

1. JewsUnited StatesPolitics and government. 2. ZionismUnited States. 3. Holocaust , Jewish (19391945)Public opinion. 4. Public opinionUnited States 5. United StatesEthnic relations. 6. Public opinionJews. 1. Title.

E184.J5B492 1990

320.540956940973dc20

9011942

CIP

http://wsupress.wayne.edu/

CONTENTS

CHAPTER II A REORDERING OF PRIORITIES: THE HOMELAND UNDER SIEGE

CHAPTER III WAR AND STATEHOOD

CHAPTER IV AMERICAN ZIONISM AND THE HOLOCAUST

CHAPTER V THE AMERICAN ZIONIST LOBBY, 19431945: A SUMMARY AND A CASE STUDY

CHAPTER VI THE TRIUMPH OF AMERICAN ZIONISM

CONCLUSIONS

NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

FOR MY WIFE, AMY MITTELMAN, AND MY PARENTS, HARRY AND ROSE BERMAN

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I owe my thanks to the many people who have contributed to this book. I am particularly grateful to the librarians and archivists who patiently responded to my numerous requests. Sylvia Landress and her staff at the Zionist Archives and Library were especially helpful as was Miriam Leikind of the Abba Hillel Silver Memorial Archives. I also appreciate the efforts of the staffs of the American Jewish Historical Society, the Herbert H. Lehman Papers, the National Office of Hadassah, and the Jabotinsky Institute. Daniel Schnurr, the social science reference librarian of Hampshire College, generously provided me with references and support.

I owe a special debt to Professor Walter P. Metzger of Columbia University and Professor David S. Wyman, of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Professor Metzger was an excellent dissertation sponsor. His insightful comments and probing questions were numerous and his editorial suggestions invaluable. Professor Wyman, as a friend and mentor, was generous with his time and support. I can honestly say that this book would not have been completed without their help.

Professors James P. Shenton, Paula Hyman, and Rosalind N. Rosenberg read most of this manuscript and offered important suggestions. I would like to especially thank Professor Shenton and Professor Peter Onuf for their support and encouragement during my years as a graduate student at Columbia University. Professors Henry Feingold and Monty Penkower helped me understand the complex history of American Jewry during the 1930s and 1940s. Many colleagues at Hampshire College offered their encouragement and posed difficult and probing questions. Leonard Click was an important source of inspiration. I relied upon Penina Glazer, the Dean of the Faculty, for friendship, advice, and release time. I am also grateful for the support of Eqbal Ahmad, Nancy Fitch, Allen Hunter, Bob Rakoff, and Miriam and Paul Slater.

I have been lucky enough to be associated with a group of scholars who have been true comrades for many years. A special thanks to Elizabeth Capelle, Dan Richter, Diana Shaikh, and Herbert Sloan. Thanks also to Harriet Goldstein, Howard Berman, my late grandmother Sarah Feller, the late Leo Mittelman, Bea Mittelman, Midge Wyman, and Kirsten and Lia Meisinger who provided support and love for many years.

Both Ms. Anne Adamus and Dr. Robert R. Mandel of Wayne State University Press have been very helpful and unusually patient. I hope that this book will meet their expectations. As should be obvious, while many individuals have contributed to the appearance of this book, I am solely responsible for any errors of fact and judgment.

I cannot adequately express my gratitude to my parents, Rose and Harry Berman. All I can do is dedicate this book to them and to my wife, Amy Mittelman. To Amy I owe much. As a talented historian she set an example I tried to emulate and as a friend and companion she successfully got me through more crises than I care to remember. Finally, I thank my son, Louis, for the hearty laughs and big hugs which helped me keep the task of writing this book in perspective.

INTRODUCTION

I n 1943, the American Zionist leader Hayim Greenberg accused American Jewish organizations of moral bankruptcy for failing to mobilize to come to the aid of European Jewry. Greenberg, writing in the Yiddish press, marveled at the lack of a frenzied response on the part of a people who had learned that millions of their brethren were being brutally eliminated. His claim that the great number of competing organizations that made up the American Jewish community divided rather than united American Jewry, anticipated the judgment of historians. Greenberg and subsequent scholars, however, tended to ignore an intriguing fact: during the Holocaust era, American Zionist organizations experienced tremendous growth and Zionists became the leaders of the American Jewish community.

In 1933, the year Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany, Zionism was a weak movement struggling to survive within the American Jewish community. The major American Zionist organizations in 1933 claimed a combined membership of slightly over sixty-five thousand. In the midst of a major depression, Zionists vainly fought to convince American Jews to join a movement that seemed to be doing little to uplift the Jewish condition either at home or abroad. To make matters worse, within the United States powerful American Jewish organizations, such as the American Jewish Committee and the entire Reform Judaism establishment, refused even to accept the very concept of Jewish nationhood.

On the eve of the Nazi nightmare, Zionist leaders in the United States, like their counterparts in Palestine, did not expect to see the establishment of a Jewish state in their lifetimes. Instead, they looked forward to a slow but steady Jewish settlement of Palestine under the supervision of Great Britain, which held a League of Nations Mandate to prepare the Holy Land for eventual independence. While this strategy did not promise to immediately alleviate the Jewish problem in Europe, it would allow for social experimentation and, through the kibbutz movement, the establishment of a classless Jewish society in Palestine. Slow-paced development would also provide Zionists with time to forge a peaceful relationship with the Arab residents of Palestine. While Palestines Arab majority might be uncomfortable with Jewish settlement in 1933, most American Zionist leaders optimistically looked forward to the time when the Arabs would realize that the Zionist experiment in the Holy Land was serving their own best interests, as well as those of the Jews.