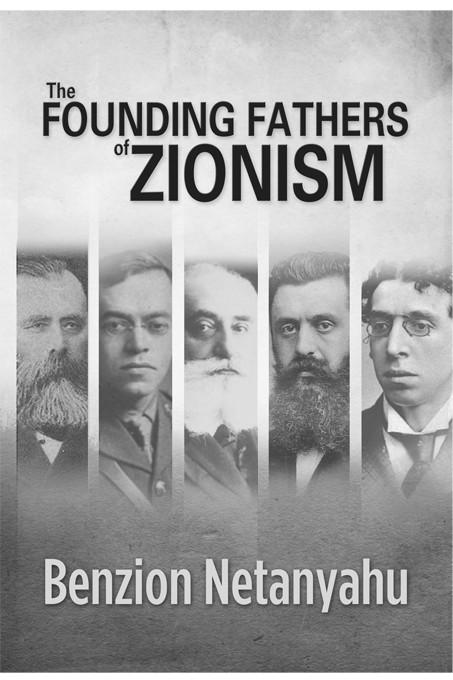

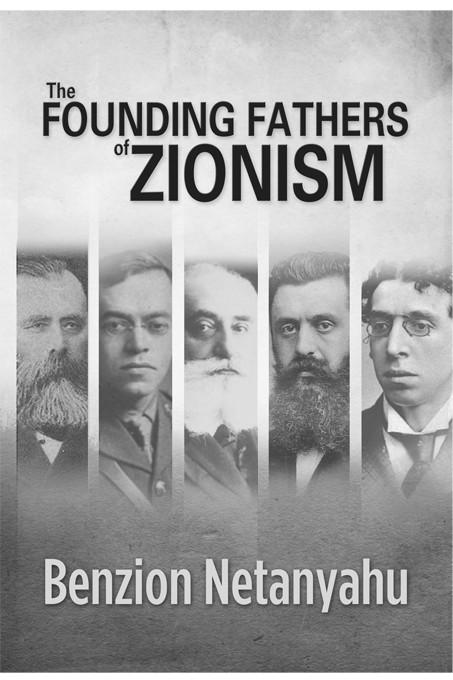

A brilliant, elegantly written work, highly original and personal in its portrayal of five of the most important of Zionist theorists, from Pinsker to Jabotinsky. The author is not only a renowned scholar, especially of the Inquisition in Fifteenth Century Spain, but also was himself an activist in the Revisionist Zionist movement and an aide to one the founders about whom he writes. The book helps understanding of the diverse political views in Israel today. Michael Curtis distinguished professor emeritus

of political science at Rutgers University

Benzion Netanyahu

First printing: March 2012

Copyright 2012 by Benzion Netanyahu. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations in articles and reviews.

Balfour Books

P.O. Box 2180

Noble, OK 73068

1 877 887 0222

www.balfourtitles.com

Co-published with:

Gefen Publishing house Ltd.

6 Hatzvi St

Jerusalem, 94386

Israel

011-972-2-5380-247

www.gefenpublishing.com

ISBN: 978-1-933267-15-9

Cover and Interior by Brent Spurlock, Green Forest, AR

For my beloved son

JONATHAN

Who sacrificed his life in

defense of his people at

Entebbe on July 4, 1976

Contents

Foreword to the English Edition

M odern Israel was built on the intellectual foundations laid by Zionisms founding fathers, much as the United States was built on the principles formulated by Americas founding fathers.

The historical, moral and political arguments developed by Leo Pinsker, Theodore Herzl, Max Nordau, Israel Zangwill and Zeev Jabotinsky changed Jewish history.

They argued that the Jewish state would save the Jewish people and serve, in the words of the great English writer George Elliott, as a beacon of freedom amidst the despotisms of the East.

These ideas have withstood the test of time. As the founding fathers predicted, without a Jewish state European Jewry was doomed. Equally, they argued that once the Jews would gather their exiles in the Promised Land and reestablish their sovereignty, they would show remarkable recuperative powers. The founding fathers of Zionism did not think antisemitic attacks would necessarily disappear once the Jews had a state of their own, but they argued presciently that a state would give them the power to defend themselves against such assaults.

The antisemitism which the founding fathers warned against, and which ultimately culminated in the Nazi horrors, has been replaced by the current onslaught of militant Islam on Israel and the West. Then, as now, the supporters of the Jewish people, and all free peoples, have much to gain from studying the insights of these prophetic men of genius. Ideas matter in the battle for freedom. They were crucial to the success of Zionism, the Jewish national movement. And they are crucial today.

In the current struggle of Israel and the West against a violent and intolerant creed, the ideals of Zionisms founders matter more than ever. They retain their pivotal importance for securing the Jewish future, and thus the future of Judeo-Christian civilization as a whole.

These five essays, three of which were originally written in Hebrew, were intermittently published over several decadessome before the Holocaust, others after the establishment of the State. Only minor editorial changes were made since. Readers will judge for themselves the merit of the analyses and the accuracy of the predictions contained in these essays, and especially the timeless relevance of the teachings of the Founding Fathers of Zionism.

B. Netanyahu

Jerusalem

Leo Pinsker

Chapter 1

A Russian physician and writer, Pinsker was born in 1821. He was the founder of Hovevei Zion (Lovers of Zion), a Jewish national movement which was the precursor of Herzls Zionist Organization. Pinsker died in 1891. (the following was originally published in Road to Freedom, Introduction, Scopus Publishing Co., New York, 1944)

I

T he national movement in modern Jewry was born both in an inopportune time and an inappropriate place. All other movements of modern European nationalism arose between 1815 and 1878, between the Congress of Vienna and the Congress of Berlin. Had the Jewish national movement emerged in this interim, it would have probably benefited from the mutual support of all other movements of national liberation. In 1881, however, when Jewish nationalism finally sprang forth, the heyday of the national idea was over and a rampant Imperialism had set in. Holding in check the remaining irredenta pockets, this Imperialism coincided with another development which further enervated the movements for self determination. The colonial expansion, with its widening spheres of trade, was paralleled by an ever-growing industrialism, and the latter gave rise to the cosmopolitan socialist creed, with its anti-national bias. It was the ill fate of Jewish nationalism to be born at a time of an ascending imperialism. It was its double misfortune that it had to rise in the shadow of the anti-national world movement of Marxism.

The development of the Jewish national movement was even more hampered by the fact that it was initiated and centered in Russia. Russia exemplified both the trends of Imperialism and Marxian Socialism. No other Imperialism of the 19 th century was involved in such bitter conflicts with the principles of nationalism as was that of Russia. Whereas the colonial aspirations of the western powers were directed toward extra-European territories, where nationalism was still inchoate and primitive, the established policy of the Russian empire was one of expansion westward on the continent, where the national feeling was mature and predominant. Moreover, in the path of Russias expansion there were people of racial affinity to the Russians, and the idea of Pan-Slavism, promulgated by the Slavophiles, had struck deep roots in Russian national psychology and tinted Russian Imperialism with a national color. Herzen, the inspiring liberal publicist, and for decades the leading figure of the Russian Intelligentsia, lost his influence when he declared his support for the national revolution in Poland. It was largely on account of this aversion to all separatist national aspirations on the part of the Russians that the public national movements in Russia were brought to a standstill after the Polish insurrection of 1863.

While the Slavophiles, the right wing of the Russian Intelligentsia, gave popular backing to the ideology of Imperialist Russia, the left wing, represented by the revolutionary elements, was equally set against the nationalist viewpoint. Russian revolutionary thought, which began with the advocacy of constitutional democracy and continued with the repudiation of every form of government, finally took a sharp turn toward Marxian philosophy with its anti-national outlook. Nevertheless, it was Russian Marxism to which the subjected national elements turned their eyes. Since the Russians did not help the oppressed nations to overthrow the Czarist yoke in the name of Nationalism, these nations attempted to help the Russians overthrow that yoke in the name of Socialism. Russian Socialism gathered, like a vast river, all the streams of revolutionary energy that flowed toward it from the subjugated peoples. It was this development that made Russian Socialism more powerful and determined than any other socialist movement in Europe; but the same development also contributed to the weakening of the national fronts.

Next page