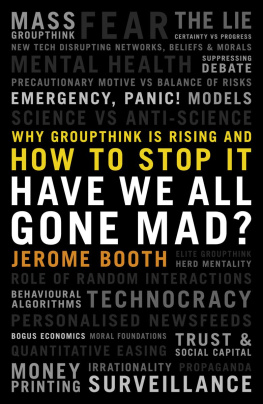

T his is a book about mass groupthink, which is a type of mass moral thinking. It is about the impact new technology is having not only on how we communicate but on how we think and self-identify, on our mutual toleration and on our politics. It is a defence of reason and science and history. It is a wake-up call for us to protect our liberal democracy.

Even before Covid-19 and lockdown, it seemed that we were living in an increasingly irrational and anxious world in which mental illness was worsening. This is odd because it follows widespread peace and clear improvements in global health, well-being and economic prosperity. Global inequality has massively reduced in my lifetime and agricultural technology means we can now amply feed the worlds projected population using less land than currently.

We have faced a series of crises which we have poorly prepared for and then dealt with badly on their arrival. Why? There seems to be some dysfunction in our politics and a lack of engagement with electorates. Our political elites and media sometimes appear to be in bubbles of their own, cut off from the majority of public opinion. viii

Have we all gone mad? Can we identify the patterns and causes of what is happening and try to stop it?

Why did the policy reaction to Covid-19 not take into account the side effects of lockdown? Why did the financial crisis of 2008 occur, and will another one happen? What is behind the recent surge in political correctness? Is net zero sensible or affordable? Why are people becoming disillusioned with democracy?

I have written this book as an attempt to explain what is going on. I argue that the less than satisfactory responses to these and other recent questions have at least one commonality. Mass groupthink is on the rise. I argue that the current heightened confusion and dissatisfaction within society, including an alienation of many from the ideas and interpretations emanating from political elites and the mainstream media, can best be understood in the context of what we know about psychology and some vicious postmodern memes (a meme here meaning a sort of intellectual virus, a sticky idea which self-replicates across society). Also, recent changes in communication technology (especially the internet and social media) have had a profound impact on the way we communicate and interact with others. They have affected our networks and communities, our sense of identity, the groups we belong to, our values and moral systems and our tolerance for others. Our Stone-Age brains have not yet adjusted to all this, and our societies and political systems havent either.

That our brains have evolved slowly compared to our technology is nothing new. Neither is great complexity in our environment and our need to depend on shortcuts in our thinking. Such shortcuts include norms of behaviour but also standard patterns of thought, ix association of ideas and concepts of right and wrong. Shortcuts in thinking are common and inevitable, and immensely useful, but can also get us into deep water. When we dont have the same ideas and values, they may be constructively challenged. When we do, the result can be collective irrationality. Our common ideas and shortcuts can seriously let us down when we face particularly marked changes in our environment. We may also find it difficult to cope if these shortcuts for whatever reason change rapidly. Yet they are fashioned by rapidly changing networks and interactions, and this is particularly worrying where such change is non-random but rather orchestrated by others for profit or control.

Of the various forms of collective irrationality, groupthink is particularly dangerous. It occurs where a partially or completely false set of beliefs is sustained through lack of effective challenge. It thrives unnoticed by those captured by it. At worst, groupthink becomes moral and binary, good versus evil; one either believes wholeheartedly or is a heretic, with no room for doubt. Transgressors can be bullied, ostracised, punished, and vigorous efforts are made to stop any challenge or debate.

Avoidance of criticism and refusal to consider alternatives, consciously or unconsciously, has led to momentous mistakes throughout history. Irving Janis, who popularised the term groupthink, which is deliberately resonant with Orwells doublethink, used as an example the uncritical thinking in the John F. Kennedy Cabinet that led to the abortive 1961 US invasion of Cuba known as the Bay of Pigs disaster. In considering the military strategy, they did not give sufficient attention to the flaws in the plan or its alternatives. Discussion was limited within unquestioned parameters. The group x assumed the President backed the invasion and nobody publicly questioned the overall wisdom of it, only the details. Afterwards, Kennedy recognised the faulty planning and adopted an approach to avoid repeats. This was then successfully deployed in the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, when it seemed the world was on the brink of nuclear war. In responding to the threat posed by the deployment of Soviet nuclear weapons in Cuba, just off the US coast, Kennedy formed groups to consider different strategic options and stayed out of them so they would not be overly influenced by his preliminary views. There was a process of rigorous challenge and consideration of different policy options. Unlike with the Bay of Pigs fiasco, good choices were made and a successful result achieved.

Janiss concept of groupthink has been used by management consultants advising on how to make better board decisions ever since. He highlighted eight groupthink symptoms: (a) an illusion of invulnerability; (b) collective rationalisation; (c) belief in the inherent morality of the group; (d) the stereotyping of those disagreeing as being deliberately opposed to the group, as well as morally weak or evil; (e) exercise of pressure on dissenters within the group to conform or leave; (f) self-censorship; (g) illusions of unanimity; and (h) self-appointed mind guards to squash heretical thinking within the group.

Although Janiss emphasis was on small-group decision-making, groupthink can be society-wide. In large-scale groupthink, as fear of transgression builds, particularly amongst elites, so too does acquiescence. Self-censorship takes hold and public discourse suffers. The very sense of the improbability that so many people could be wrong in itself sustains the lie. Indeed, there is a term for this: the Big Lie. xi

THE STRUCTURE OF THE BOOK

In Chapter 1, I look at the psychology behind groupthink. We like to think of ourselves as rational, but human beings are irrational. Rationality is something we have evolved to justify our actions to ourselves and to others after the event. Moreover, the more intelligent, educated and erudite, the more convincing we are in this task. And so elite bubbles are formed, impervious to outside reality. Our politicians and media elites are often more collectively blind than those around them.

We have different moral foundations and different groups and identities. As patterns of thought are repeated within groups and are less challenged from outside, they become stronger and help define group cohesiveness, but this also creates intolerance for the beliefs of others. Loyalty to shared values and care for those inside the group helps explain how groupthink develops.

I also discuss risk and uncertainty and criticise the widespread adoption of the precautionary motive in place of more comprehensive costbenefit analysis. By focusing on only one problem, the precautionary motive can lead to reckless disregard to side effects and other problems.