2015 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jones, J. B. (John Beauchamp), 18101866.

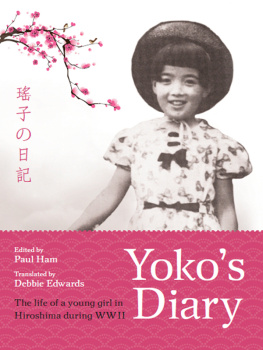

A rebel war clerks diary : at the Confederate States capital / J. B. Jones ; edited by

James I. Robertson Jr.

pages cm. (Modern war studies)

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-7006-2123-1 (cloth, volume 1 : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-7006-2155-2 (ebook, volume 1)

ISBN 978-0-7006-2124-8 (cloth, volume 2 : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-7006-2156-9 (ebook, volume 2)

1. Jones, J. B. (John Beauchamp), 18101866Diaries. 2. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Personal narratives, Confederate. 3. Confederate States of America. War DepartmentOfficials and employeesDiaries. 4. Richmond (Va.)HistoryCivil War, 18611865Sources. I. Robertson, James I., editor. II. Title.

E487.J732 2015

973.782dc23

2015016628

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10987654321

The paper used in this publication is recycled and contains 30 percent postconsumer waste. It is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1992.

Contents

Editors Preface

This volume concludes the epic diary of John Beauchamp Jones (18101866)the longest and most useful work of its kind in the annals of Civil War historiography. Although it is largely unknown outside a rather circumscribed group of Civil War scholars and buffs, Joness incredibly detailed chronicle (originally published in 1866) remains one of the top dozen printed primary sources on the Southern nation: its government, military affairs, politics, society, economics, and fluctuating morale.

A native of Maryland and a resident of Philadelphia at the outbreak of war, Jones was a journalist and novelist by trade and a strong advocate for the Confederacy. He spent the entire war as a senior clerk in the War Departments Passport Office in Richmondthe heart of the Confederacy and the principal target of Union military might. As a high-level clerk at the center of military planning, Jones was a constant spectator to men and events in the capital and enjoyed an extraordinary perspective from which to view the Southern nation in action. The position also gave him access to confidential files and command-level conversations that he regularly leaked into his meticulously kept diary. Jones quoted scores of dispatches and reports by both military and civilian authorities (including letters from Robert E. Lee not printed elsewhere). Inside the War Departments beehive of activity, Joness attentive eyes and ears missed nothing. Biases sometimes warped his judgment, but they also kept the tendency toward hero worship in check, even as they sharpened his gaze on the pretentious, selfish, incompetent, and corrupt. Jones did not respect individuals for the offices they held, and he freely heaped scorn upon those he considered deserving of criticism, including President Jefferson Davis and James A. Seddon, the secretary of war and Joness superior.

Volume II picks up where volume I left off: in midsummer 1863 and the crushing twin defeats at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. The months that followed altered the geographic and psychological landscapes for both J. B. Jones and his fellow citizens throughout the Confederacy. The expressions of hope, optimism, and surging patriotism that marked the first two years of the conflict began to fade. Events have succeeded another with disastrous rapidity, Jones wrote. Now, he concluded, the Confederacy totters to destruction. As morale slid, Southerners weaknesses appeared like a pox. Inflation, limited supplies, black markets, and extortion took a heavy toll on the population. Growing friction between the president and Congress and between the president and his generals, as well as states rights surging against a weak central government, increased the political instability. And all the while, Union might was slowly enveloping and crushing one Southern state after another.

This second volume begins on Saturday, August 1, 1863. A persistent drought and high humidity added to the discomforts of war. By then, Richmond bore little resemblance to the glowing capital of the prewar years. With a population ten times that of 1860, Richmond was shabby, besieged by refugees and convalescing soldiers, crippled by ever-rising prices charged by merchants whose shelves were half empty. Bitterness increased with hunger. In mid-July 1863 Jones had stated, We are in a half starving condition. I have lost 20 pounds, and my wife and children are emaciated to some extent. The situation did not improve. Near the end of that year, Jones wrote blandly: Such is the scarcity of provisions that rats and mice have mostly disappeared, and the cats can hardly be kept off the table. He asked his journal: When will this years calamities end? Still, he viewed the start of 1864 with hope. We look for a healthy year, everything being so cleanly consumed that no garbage or filth can accumulate. We are all good scavengers now, and there is no need of buzzards in the streets. Joness diary entries reflect the growing unrest and despair. A year later he stated succinctly, What I fear most now is starvation. Rats in the kitchen ate crumbs from his daughters hand. Perhaps we shall have to eat them! the war clerk exclaimed.

The long, climactic siege of Richmond began in the summer of 1864. Jones wrote, Valor alone is relied upon now for our salvation. Even that seemed to evaporate as the months passed. Many of the privates in our armies. he noted, are fast becoming what is termed machine soldiers, and will ere long cease to fight wellhave nothing to fight for. Jones kept up to the end his incisive comments on civilian attitudes toward Confederate military strategy. He fired steady salvos at the ineffectual national government and the shortsightedness of state governors. Through it all, Jones saw himself as a helpless pawn caught in a conflagration he could only witness and record. In his final entry, still with a journalists eye, he wrote: I never swore allegiance to the Confederate States Government, but was true to it.

The sheer scope and size of what Jones produced attest to his dedication and success. The result is the only continuous record of the Civil War from beginning to end as seen from Richmond. In the words of one historian, Joness diary is a microscopic view of the Confederacy; of alternating waves of hope and despair; of privation and suffering among civilians; of bickering between Jefferson Davis and the military figures; of discord between Davis and Congress; of the destructive conflict between state and central government. The American heritage and our comprehension of the Civil War are much richer because of Joness remarkable devotion to history.

James I. Robertson Jr.