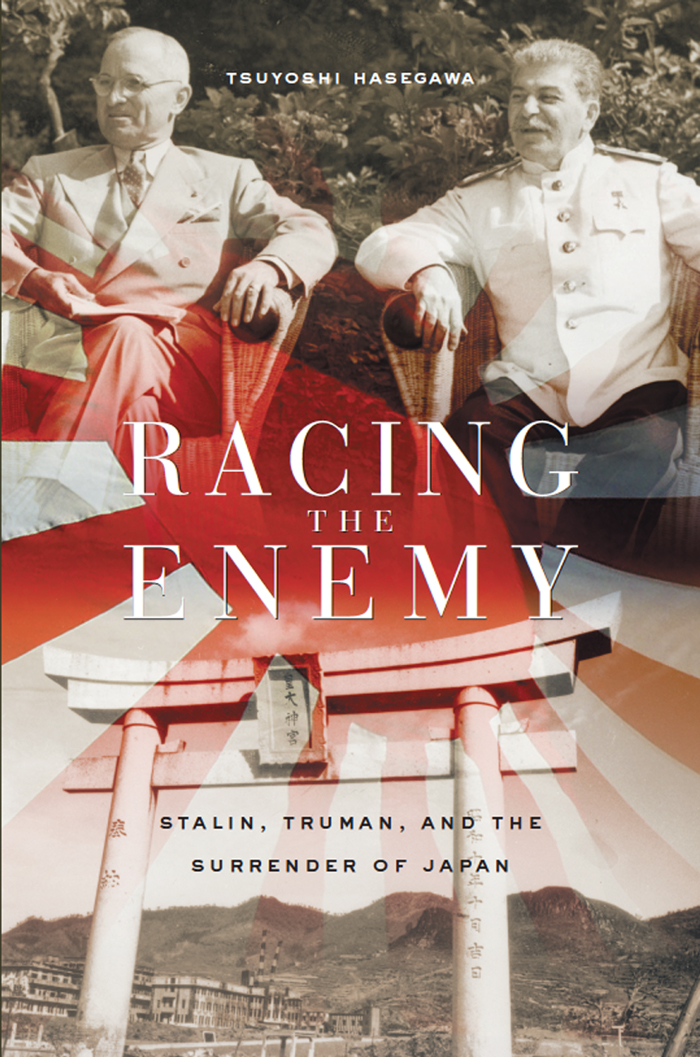

RACING

THE

ENEMY

RACING

THE

ENEMY

STALIN, TRUMAN, AND THE SURRENDER OF JAPAN

TSUYOSHI HASEGAWA

THE BELKNAP PRESS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England

Copyright 2005 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2006

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hasegawa, Tsuyoshi, 1941

Racing the enemy : Stalin, Truman, and the surrender

of Japan / Tsuyoshi Hasegawa.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13 978-0-674-01693-4 (cloth)

ISBN-10 0-674-01693-9 (cloth)

ISBN-13 978-0-674-02241-6 (pbk.)

ISBN-10 0-674-02241-6 (pbk.)

1. World War, 19391945Armistices. 2. World War, 19391945Japan.

3. World War, 19391945Soviet Union. 4. World War, 19391945

United States. 5. World politics19331945. I. Title.

D813.J3H37 2005

940.532452dc22 2004059786

In memory of

BORIS NIKOLAEVICH SLAVINSKY,

my friend and colleague,

who did not see the fruit of our collaboration

Contents

For Russian words, I have used the Library of Congress transliteration system except for well-known terms such as Yalta and Mikoyan when they appear in the text; in the citations, I retain Ialtinskaia konferentsiia and Mikoian. Soft signs in proper nouns are omitted in the text but retained in the notes; hence Komsomolsk instead of Komsomolsk. I employ the strict Library of Congress transliteration system for the ending ii rather than the more popular ending y; hence Maiskii instead of Maisky and Lozovskii instead of Lozovsky.

For Japanese words, I use the Hepburn transliteration system with some modifications; hence Konoe instead of the more commonly used Konoye. But I use nenpyo instead of the strict Hepburn rendering nempyo. In addition, I use an apostrophe in some cases for ease of reading; for instance, Shunichi instead of Shunichi, to separate shun and ichi. Macrons in Japanese names and terms are omitted.

Japanese given names come before surnames in the text, but the order of surnames and given names follows the Japanese custom in the endnotes, except for Japanese authors of English- or Russian-language books and articles. For instance, Sadao Asadas Japanese article is cited as Asada Sadao, but his English article is cited as Sadao Asada.

For Chinese geographical names I use the Postal Atlas system. For Chinese personal names I follow contemporary style rather than the pinyin system; hence Chiang Kai-shek rather than Jiang Jieshi, and T.V. Soong rather than Song Ziwen.

For proper names in direct quotes from original documents I retain the usage in the original, although these renderings may not conform to the system I use in the text. Thus, the Kurils may appear as the Kuriles and Konoe as Konoye in direct quotes.

S IXTY YEARS AFTER the dropping of the atomic bomb and the Japanese surrender, we still lack a clear understanding of how the Pacific War ended. Historians in the United States, Japan, and the Soviet Union, the three crucial players in the drama of the wars end, have focused on a small piece of a large picture: Americans on the atomic bomb, Japanese on how Emperor Hirohito decided to end the war, and Russians on Soviet military actions in the Far East. But a complete story has not yet been told.

In the United States debate has continued as to whether the atomic bomb was directly responsible for Japans surrender. As the 1995 controversy over the Enola Gay exhibit at the Smithsonians National Air and Space Museum reveals, the atomic bombs used on Hiroshima and Nagasaki continue to strike Americas raw nerves. But this debate has been strangely parochial, concerned almost entirely with the American story.

The intense drama leading to Japans decision to surrender in the last days of the Pacific War has likewise fascinated the Japanese. Despite a continuous stream of publications on this subject, no serious scholarly work has critically analyzed Japans decision in the broader international context. Until now, Robert Butows study of Japans surrender has been the most complete scholarly analysis on the topic in both Japan and the United States.

The works of Soviet historians bear the marks of the ideological strait-jacket the Marxist-Leninist state imposed during the postwar period.

Significantly, American and Japanese historians have almost completely ignored the role of the Soviet Union in ending the Pacific War. To be sure, the issue of whether the Truman administration viewed the use of the bomb as a diplomatic weapon against the Soviets has created a sharp division between revisionist and orthodox historians in the United States. Yet even here, the focus remains on Washington, and the main point of contention is over American perceptions of Soviet intentions. Standard accounts of the end of the Pacific War depict Soviet actions as a sideshow and assign to Moscow a secondary role at best.

An International History

This book closely examines the end of the Pacific War from an international perspective. It considers the complex interactions among the three major actors: the United States, the Soviet Union, and Japan. The story consists of three subplots. The first is the combination of competition and cooperation that played out between Stalin and Truman in the war against Japan. Although the United States and the Soviet Union were allies, Stalin and Truman distrusted each other; each suspected that the other would be the first to violate the Yalta Agreement governing their relationship in the Far East. The Potsdam Conference, which met from July 17 to August 2, 1945, triggered a fierce race between the two leaders. While it became imperative for Truman to drop the atomic bomb to achieve Japans surrender before the Soviet entry into the war, it became equally essential for Stalin to invade Manchuria before Japan surrendered. This book examines how the Allies Potsdam Proclamation issued to Japan, the atomic bombs, and the Soviet entry into the war were intertwined to compel Japans acceptance of unconditional surrender.

The Soviet-American rivalry is carried beyond the emperors acceptance of unconditional surrender on August 14. Far from abating, Soviet military maneuvers in the Far East accelerated after Moscow learned of Japans intention to surrender, a point often missed in existing accounts of the wars end. It was only after Japans acceptance of the Potsdam surrender terms that Stalin ordered the Kuril and Hokkaido operations. While the Japanese were preparing to accept surrender, Stalin and Truman were engaged in an intense tug of war to gain an advantage in the postwar Far East.

The second subplot is the tangled relationship between Japan and the Soviet Union, characterized by Japanese courtship and Soviet betrayal. The more the military situation deteriorated, the more Japanese policymakers focused on the Soviet Union. For the army, determined to wage a last-ditch battle to defend the homeland, it became essential to keep the Soviet Union out of the war. For the peace party, the termination of the war through Moscows mediation seemed to offer the only alternative to unconditional surrender. At the same time, Japans overtures served Stalins interests by providing an opportunity to prolong the war long enough for the Soviets to join it. Even after the Potsdam Proclamation was issued, the Japanese clung to the hope that Moscow mediation would bring about more favorable surrender terms. Thus Soviet entry into the war shocked the Japanese even more than the atomic bombs because it meant the end of any hope of achieving a settlement short of unconditional surrender. Eventually, the fear of Soviet political influence in Japans occupation drove the emperor to accept unconditionally the Potsdam surrender terms.