Chang-tai Hung - Politics of Control: Creating Red Culture in the Early People’s Republic of China

Here you can read online Chang-tai Hung - Politics of Control: Creating Red Culture in the Early People’s Republic of China full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: University of Hawaii Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

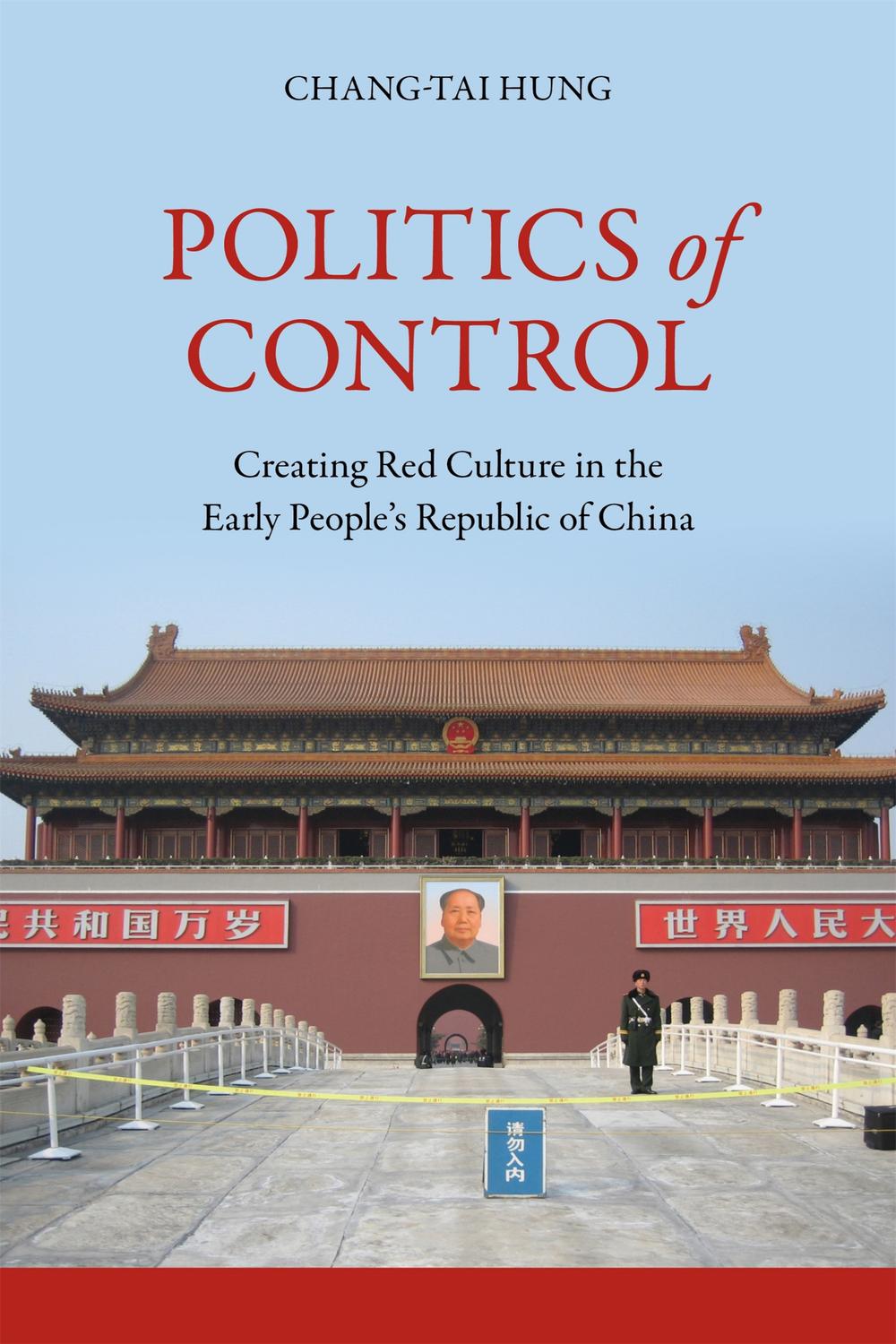

- Book:Politics of Control: Creating Red Culture in the Early People’s Republic of China

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Hawaii Press

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Politics of Control: Creating Red Culture in the Early People’s Republic of China: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Politics of Control: Creating Red Culture in the Early People’s Republic of China" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Using a unique interdisciplinary, cultural-institutional analysis, Politics of Control is the first comprehensive study of how, in the early decades of the Peoples Republic of China, the Chinese Communist Party reshaped peoples minds using multiple methods of control. With newly available archival material, internal circulars, memoirs, interviews, and site visits, the book explores the fascinating world of mass media, book publishing, education, religion, parks, museums, and architecture during the formative years of the republic.

When the Communists assumed power in 1949, they projected themselves as not only military victors but also as peace restorers and cultural protectors. Believing that they needed to manage culture in every arena, they created an interlocking system of agencies and regulations that was supervised at the center. Documents show, however, that there was internal conflict. Censors, introduced early at the Beijing Daily, operated under the twofold leadership of municipal-level editors but with final authorization from the Communist Party Propaganda Department. Politics of Control looks behind the office doors, where the ideological split between Party chairman Mao Zedong and head of state Liu Shaoqi made pragmatic editors bite their pencil erasers and hope for the best. Book publishing followed a similar multi-tier system, preventing undesirable texts from getting into the hands of the public.

In addition to designing a plan to nurture a new generation of Chinese revolutionaries, the party-state developed community centers that served as cultural propaganda stations. New urban parks were used to stage political rallies for major campaigns and public trials where threatening sects could be attacked. A fascinating part of the story is the way in which architecture and museums were used to promote ethnic unity under the Chinese party-state umbrella. Besides revealing how interlocking systems resulted in a pervasive method of control, Politics of Control also examines how this system was influenced by the Soviet Union and how, nevertheless, Chinese nationalism always took precedence. Chang-tai Hung convincingly argues that the PRCs formative period defined the nature of the Communist regime and its future development. The methods of cultural control have changed over time, but many continue to have relevance today.

Chang-tai Hung: author's other books

Who wrote Politics of Control: Creating Red Culture in the Early People’s Republic of China? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.