Table of contents

Pages

Landmarks

An introduction

to the European

Convention

on Human Rights

Martyn Bond

Council of Europe

Facebook.com/CouncilOfEuropePublications

Human rights in Europe

Human rights for our time

This book offers a guide for the general reader to someof the key issues of human rights in Europe. If you areinterested in knowing more about human rights yourrights and how the Council of Europe protects andpromotes them, read on. You will find a first section thatlists the rights in the European Convention on HumanRights (the Convention) and its various protocols, thena section describing some of the cases that illuminatehow these rights affect people in practice. A furthersection briefly describes how the European Court ofHuman Rights (the Court) functions, another describeshow the Council of Europe tries in other ways to protect and promote human rights across the continent,and finally there are some comments on how humanrights in Europe may expand and be strengthened inthe near future.

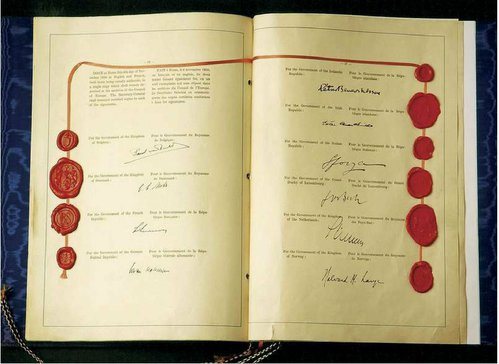

The 10 initial signatories of theConvention in 1950 were Belgium,Denmark, France, Ireland, Italy,Luxembourg, the Netherlands,Norway, Sweden and the UnitedKingdom. Since then all statesjoining the Council of Europe havesigned and ratified the Convention.

In these pages you will find a simple description ofwhat is a complex system. The Council of Europe is anumbrella organisation that brings together 47 states topromote democracy, human rights and the rule of law.It works by setting standards for the whole continentthrough conventions agreed and then signed andratified by as many of the member states as possible.Being a central concern, the European Convention onHuman Rights was the very first convention agreedby the states that set up the Council of Europe over65 years ago, and it has been signed and ratified byall states that have since then joined the Council ofEurope.

The Convention for the Protection of Human Rightsand Fundamental Freedoms the full title of theEuropean Convention on Human Rights was signed in1950 and came into force in 1953. The Convention didnot come out of thin air. Like the Universal Declarationof Human Rights, promulgated by the United Nations(UN) in December 1948, it was the product of itstime, the years immediately following the SecondWorld War. The UN declaration was and remains adocument of great moral value and authority, but itdoes not establish mechanisms for implementing therights it proclaims for individuals. The UN InternationalCourt of Justice, also known as the World Court, hearscases brought by states, not individuals, and likewisethe International Criminal Court, dealing with cases ofgenocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes.

It does not put the member governments in the dockif they break the Universal Declarations lofty aspirations. The Convention went further and establishedthe European Court of Human Rights, setting uplegal mechanisms to enforce meaningful respect forhuman rights in Europe.

In the opening declaration of the Convention theinitial 10 states declared their resolution as governments of European countries which are like-mindedand have a common heritage of political traditions,ideals, freedom and the rule of law, to take the firststeps for the collective enforcement of certain of therights stated in the Universal Declaration.

NEVER AGAIN!

It was the devastating experience of the Second WorldWar that led European statesmen to strengthen theprotection of the rights of individuals vis--vis thestate. Arbitrary arrests, deportations and executions,imprisonment without charge, concentration campsand genocide, torture and show trials were part of veryrecent experience across much of Europe. Europeanleaders wanted to protect future generations fromsuch experiences. Never again was their watchword.

Western Europe learnt from its past mistakes. Thosewho wrote the European Convention on Human Rightsdared to hope that there would never again be warin Europe and never again the abuse of human rightsthat it had brought with it. The Council of Europe,which was established in 1949, reflects a system ofinternational relations based on the values of humanrights, democracy and the rule of law values clearlydistinct from those underpinning either fascism orcommunism. The very first Convention of the newlyestablished Council of Europe was the EuropeanConvention on Human Rights.

It not only lists civil and political rights for individuals,it also gives everyone in Europe practical protectionfor their rights by imposing obligations on states. TheConvention ensures the right of individual petition,which allows any individual to bring a case to theCourt against his or her own state. It also providesfor collective enforcement of the judgments of theEuropean Court of Human Rights, with states exposedto peer pressure and review by their colleagues in theCommittee of Ministers, a body that sits in Strasbourgand reviews the Courts judgments to check thatmember states follow up what the Court decides.

The European Convention on Human Rights

Some of the most pressing political and ethical issuesof our day relate to human rights. Whether the focusis on the treatment of those detained in the waragainst terror, on abortion or assisted suicide, onthe freedom of the press or on the right to privacy,on gay marriage or on the restitution of property, allthese issues involve human rights as laid down inthe Convention. Although signed over 65 years ago,it is now more than ever a document for our times.

The European Convention on Human Rights andthe Court were created in the democratic states ofwestern Europe in the 1950s, largely as a reactionto the recent flagrant abuses of human rights underfascism. They were later strengthened to contrast withthe distortion of due legal process through one-partyrule in the eastern half of Europe that was then undercommunist domination.

Since then, growing numbers of people in Europe haveenjoyed legal protection for a long list of rights andfreedoms. They have at their disposal the EuropeanCourt of Human Rights before which they can demandredress if they think these rights have been abused.With the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the collapseof communism across central and eastern Europe,and the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991, manynew states joined the Council of Europe. Now all47 member states from Iceland to Armenia, fromPortugal to Russia accept the jurisdiction of theEuropean Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, andthe Convention must be ratified by each state whichjoins the Council of Europe. All now subscribe to theprotection and promotion of democracy, human rightsand the rule of law, and in one form or another all 47of them have built the Convention into their nationallaw. Their observation of it may be patchy and abusesof human rights certainly occur in Europe, but they canbe brought before a court where the individual canseek redress against the state that has abused his orher rights. Nowhere else in the world can you do that.

The Convention acts as anexample to other regions ofthe world. The Organisation ofAmerican States has established acourt for the protection of humanrights. The African Union has alsoadapted the European model.

But the Convention has not banished war from thecontinent of Europe. The invasion of Cyprus by Turkeyin the 1970s, the Balkan Wars of the 1990s, the Russo-Georgian war of 2008 and the more recent conflictbetween Russia and Ukraine involving the occupationof Crimea and incursions in Eastern Ukraine have givenrise to thousands of individual cases against the belligerents. They have also triggered cases by one stateagainst another, the historic ones now settled, butthe more recent ones still pending before the Court.