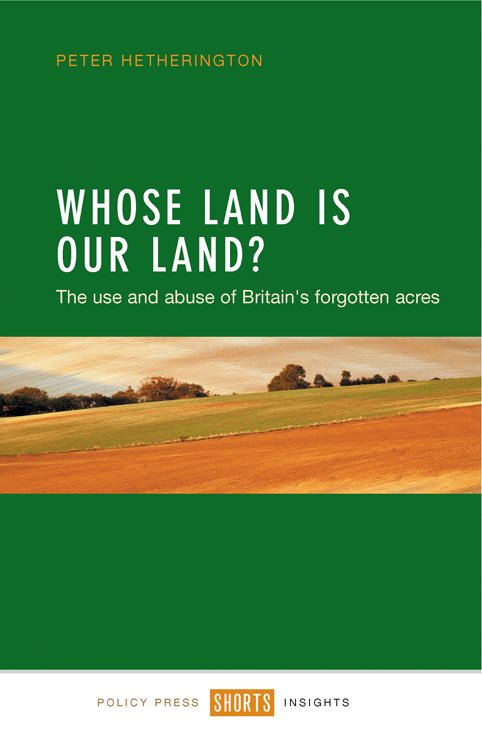

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

Policy Press University of Bristol 1-9 Old Park Hill Bristol BS2 8BB UK Tel +44 (0)117 954 5940 e-mail

North American office: Policy Press c/o The University of Chicago Press 1427 East 60th Street Chicago, IL 60637, USA t: +1 773 702 7700 f: +1 773-702-9756 e:

Policy Press 2015

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested.

ISBN 978-1-4473-2532-1 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-4473-2534-5 (ePub)

ISBN 978-1-4473-2535-2 (Mobi)

The rights of Peter Hetherington to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved: no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission of Policy Press.

The statements and opinions contained within this publication are solely those of the author and not of the University of Bristol or Policy Press. The University of Bristol and Policy Press disclaim responsibility for any injury to persons or property resulting from any material published in this publication.

Policy Press works to counter discrimination on grounds of gender, race, disability, age and sexuality.

Cover design by Andrew Corbett

Front cover: image kindly supplied by Getty

This book has been optimised for PDA.

Tables may have been presented to accommodate this devices limitations.

Image presentation is limited by this devices limitations.

Contents

Sometime in the 1970s, the late chairman of the former Highlands and Islands Development Board railed against the unacceptable face of feudalism. It was a time of great uncertainty for people whose livelihood depended on estates in northern Scotland. Ownership was sometimes hotly contested as holdings were broken up and assets stripped, with little, if any, consideration for the inhabitants. As Scottish correspondent for The Guardian , reporting these events, it led to a growing fascination with our land. On long car journeys up north from our (then) Edinburgh home, our daughters Laura and Mairi would point towards hill, loch or distant island and ask: Who owns all that? I would make an attempt to answer. It became a game.

So began a longer journey, writing occasionally about land, plodging across moorland and mountain to record the vagaries of ownership. Moving south, the fascination grew. However, journalists depend on the knowledge and guidance of others to turn ideas into hopefully something readable. So, grateful thanks to Professor Philip Lowe, of Newcastle Universitys Centre for Rural Economy, for his encouragement, support and wise counsel. Kate Henderson and Hugh Ellis, Chief Executive and Policy Director of the Town and Country Planning Association, respectively, deserve special thanks for their valuable insights. George Dunn, Chief Executive of the Tenant Farmers Association, has been a font of considerable knowledge. Ditto many others. In addition, the late Professor Sir Peter Hall was immensely generous with his time, and wisdom. Special thanks to the estimable Murdo Macleod, photographer extraordinary, for permission to use his superb Highlands and Islands photographs. Andrew Farrell proved invaluable with photographic help.

Many thanks also to Policy Press Emily Watt, Laura Vickers and others for their enthusiasm and support.

Thanks and love, most of all, to Christine for both putting up with me and joining me on the journey. Much love to Laura, Mairi, Andrew and Craig and to Dominic, Hamish, Wilbur and Edie as they discover our glorious land.

ONE

Land for all?

This land is your land

This land is my land

From the Downs to the Western Highlands

From the oak wood forest to the Lakeland waters

This land was made for you and me.

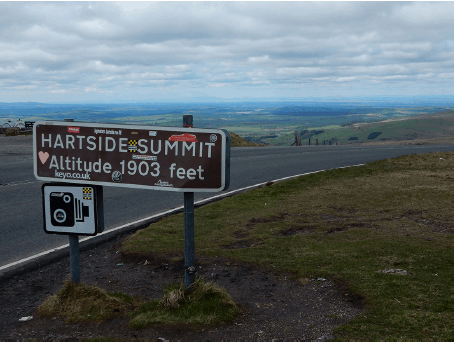

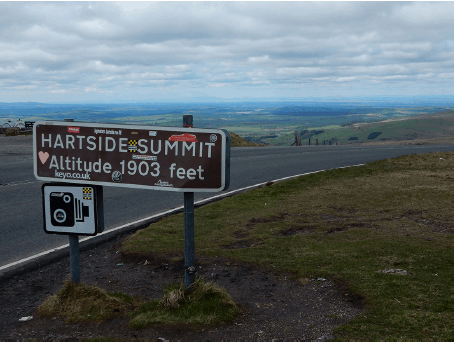

To reach the summit of the Hartside Pass, high in the North Pennines, is to marvel at the rich tapestry that is the British landscape: our land. From this Cumbrian vantage point, you can view prime pasture, marginal upland, mountain top and forested fell-side, moorland, wide estuary, and adjoining coastal plains on the English and Scottish sides of the Solway Firth. The spirits can be lifted, the inner soul replenished, by the infinite variety on offer in this slice of our land to which we can surely claim a moral, if not a legal, right as UK citizens.

No other place in a small island offers such a panoramic sweep across England and into Scotland: two nations broadly sharing a system of ownership that, in some areas, has remained relatively unchanged for centuries. But for how much longer?

Below the immediate summit of Hartside, one of the highest roads in England, the rich dairy farmland of the Eden valley rolls into the extensive holdings of one of the countrys oldest aristocracies the Lowthers stretching back to the 11th century and the subsequent largesse of Edward I. It provides a lush, pastoral foreground to the majestic peaks of the Lake District westwards, the ultimate summit of England, which incorporates the biggest single chunk of land owned by the UKs largest conservation and membership charity, the National Trust.

Hartside ... our varied land in microcosm England and Scotland below the summit (Source: Andrew Farrell)

The spectacular view from the Hartside summit for me, the most varied, breathtaking vista in Britain reveals not only our island in microcosm, but also the concentrated pattern of landownership that has long characterised Britain, briefly disturbed by an English civil war in the 17th century. It provides a starting point to raise several questions about our land, and the true value we place upon it beyond the sometimes obscene monetary gain from either trading it or using it as a shelter from taxation (of which more later).

When our island particularly England faces the challenges of sustaining a growing population, it is surely reasonable to ask why the UK government has no active land policy to address the pressures of feeding, watering and housing the population as climate change, and rising sea levels, threaten our most productive acres. with little, if any, fiscal measures to curb current trading excesses and, hopefully, bring down the cost of land for housing and for farming.

So obsessed are governments with the whims of the free market (free for whom?) that we seem to have lost any sense of proportion. We are, at best assuming we even consider the pressures on our land locked into a cycle of despair, of inevitability, a Why bother? mentality that precludes any sensible intervention in the interests of all the people. It was not always like this.

Beyond the moral, if not the legal, interest (stake?) that we all have in our land as citizens of the UKs diverse nations, it is useful to ponder one glaring contradiction: while society has changed immeasurably during the 20th century and into the 21st, the ownership of our land remains remarkably concentrated. This, as we shall see, is in spite of a transfer in ownership from the big landed estates to former tenant farmers in the 1920s and 1930s, heavy taxation viewed as penal by the aristocracy during that period, and the vague post-war commitment never realised for the public ownership of our land. As the geographer Professor Richard Munton has noted, of the 80+ per cent of rural land owned by private individuals, family trusts and corporations, a significant proportion remains in the hands of a few owners.

Next page