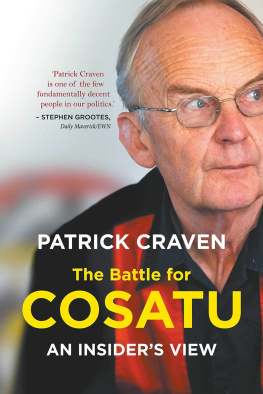

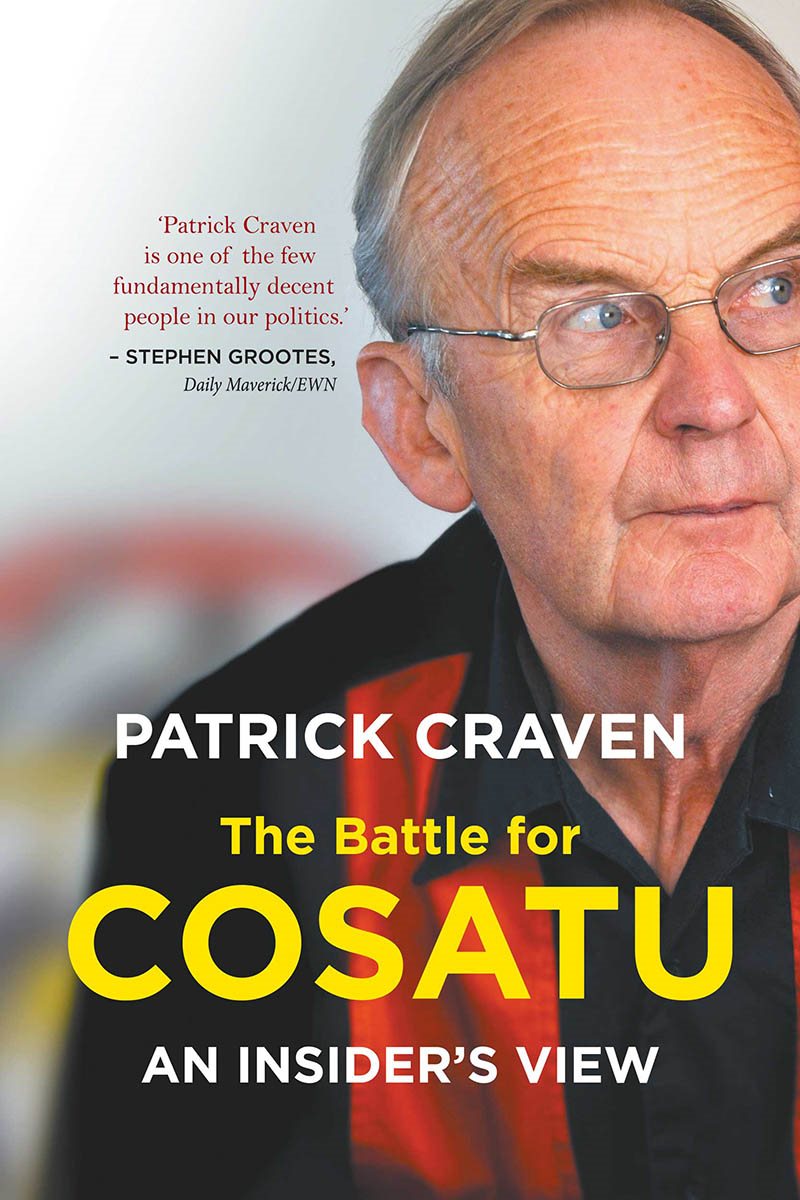

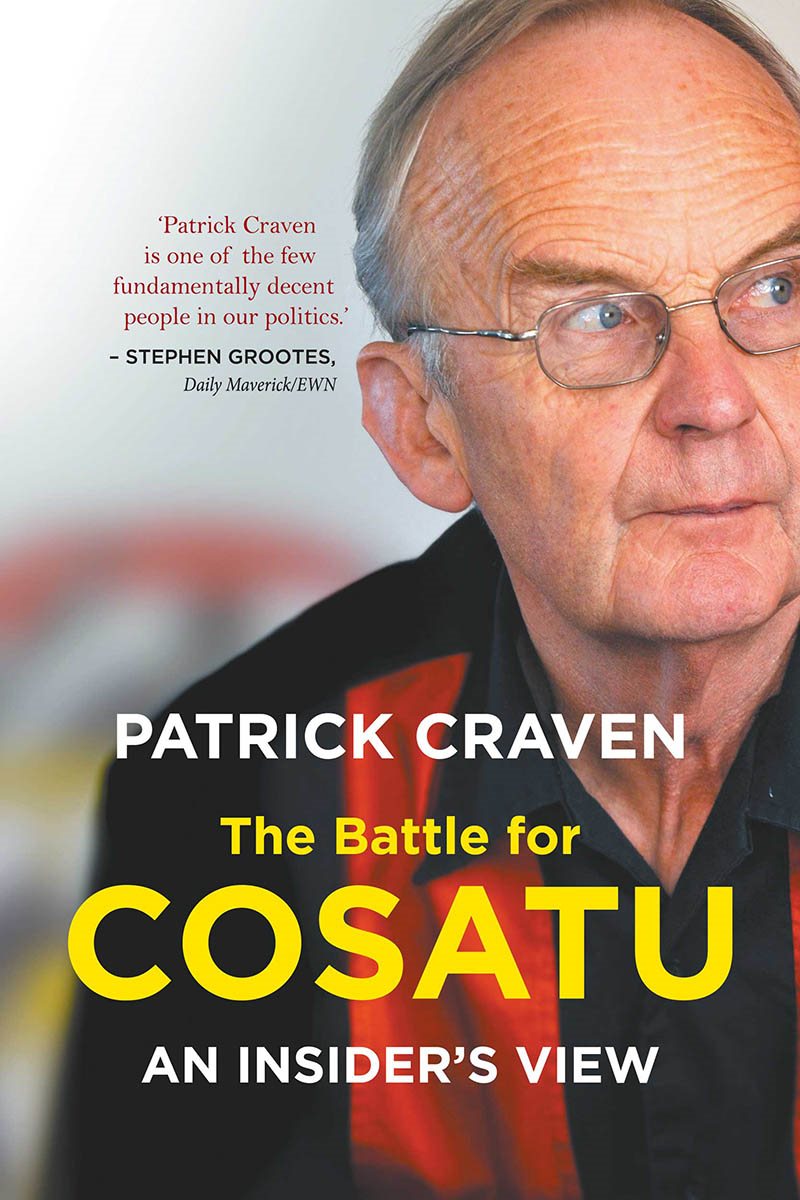

THE BATTLE FOR COSATU

An Insiders View

PATRICK CRAVEN

Patrick Craven, 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission from the copyright holder.

ISBN: 978-1-928257-19-6

e-ISBN: 978-1-928257-20-2

Published by Bookstorm (Pty) Ltd

PO Box 4532

Northcliff 2115

Johannesburg

South Africa

www.bookstorm.co.za

Edited by Tracey Hawthorne

Proofread by Kelly Norwood-Young

Cover design by publicide

Cover image by Gallo Images- Financial Mail -Robert Tshabalala

Book design and typesetting by Triple M Design

Ebook by Liquid Type Publishing Services

CONTENTS

Annexures

INTRODUCTION

This story begins in the run-up to the 11th National Congress of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) in September 2012, though it has its roots much further back before the genesis of South African democracy in 1994, and even before the federations birth in December 1985. It ends with the expulsion of the federations biggest affiliate, the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (Numsa), and Cosatus general-secretary Zwelinzima Vavi.

I was born in England in 1943. My interest in the South African liberation struggle goes back a long time, to when I was at the University of Sussex in the United Kingdom (UK) between 1961 and 1964, where one of my fellow students was Thabo Mbeki. I was involved in setting up an anti-apartheid society; and on 13 June 1964 we organised a march from Brighton to London after the Rivonia Trialists, including Thabos father Govan, were found guilty of high treason and were expected to be sentenced to death. The march of 52 miles (84 kilometres) took place in pouring rain. A petition signed by 664 staff and students from the university was handed to the British prime minister, after which we held a demonstration outside South Africa House in Trafalgar Square.

For the next three decades I was embroiled in British revolutionary politics as a member of the Revolutionary Socialist League, commonly known as the Militant Tendency (today the Socialist Party), first in London, then for 11 years in Scotland (where I met and married my wife Norma from Dundee), then back in London for a further six years.

But I never lost my interest in South Africa. At a Labour Party conference in the late 1960s, as a delegate from the Norwood Labour Party, I successfully moved a resolution on South Africa, which, among other things, called for a boycott of South African goods. This helped to build momentum for the later international sanctions campaign.

When we moved to London in 1984, Norma met members of the Marxist Workers Tendency (MWT) of the African National Congress (ANC) and became a committed member, organising solidarity support for workers struggling to overthrow apartheid and build the workers movement.

When Cosatu was born in 1985 we recognised this as a huge step forward in the struggle against apartheid, and for transforming workers lives and for socialism. We were soon proved right, when the new federation mobilised millions of workers on to the streets in massive stayaways.

Cosatu was always front and centre of the workers struggle. Apartheid was brought to its knees not by the business leaders who sat around tables and drank whisky with the exiled ANC leaders, but by the massed ranks of the working class, led by Cosatu. Their mass action on the streets left the capitalists with no alternative but to try to find a compromise with the ANC leaders and prevent what would otherwise have been a far bigger social upheaval and a greater threat to their profits.

When MWT members returned home to South Africa in the early 1990s, we were invited to join them. Norma and I left the UK for South Africa in August 1992. I had obtained permanent-resident status in South Africa, and employment managing a computer education centre in Springs.

We soon got involved in the Johannesburg East branch of the ANC, and for a few weeks leading up to South Africas first democratic general election on 27 April 1994 I was its election organiser. This involved potentially violent confrontations with Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) members from the hostels around Malvern, where we lived: we set up a table in Jules Street to distribute ANC pamphlets and were regularly confronted by aggressive IFP supporters. This even made headlines in Dundee, Scotland, where it was reported that former Dundonian Norma had been threatened with death on the streets of Johannesburg.

In that historic election, permanent residents like us were allowed to join the long queues to vote, and that was an experience we shall never forget.

After a brief spell helping to run the computer education centre in Springs from 1992 to 1994, I was employed to launch and become the director of the Workers Library and Museum, the inspiration of historian Luli Callinicos. It was in Newtown, in an old municipal workers hostel, part of which was furnished to show the shocking living conditions of workers under apartheid. I showed this to many visiting school groups, who were already becoming aware of the brutal circumstances in which many of their forbears had lived. We also held very popular Saturday afternoon workers discussion workshops on the big issues of the day.

Then, in 2000, at a time when the financial stability of the Workers Library and Museum was very uncertain, I saw an advertisement for the post of editor of Cosatus magazine, The Shopsteward . I immediately applied, thrilled at the prospect of working for the organisation that had played such a central role in the fight for liberation and which was still leading mass battles to take forward workers revolutionary struggles.

I was interviewed by General-Secretary Zwelinzima Vavi, but was not at first successful. However, the chosen candidate changed his mind and as the runner-up I was given the job. It was the start of a long and happy relationship, during which I moved from editor to acting spokesperson and then fully fledged national spokesperson. I also did all sorts of other work, such as drafting speeches and policy documents. I made numerous friends along the way. There was no evidence then of the battles that were to develop.

As this book shows, however, in the later years it became a much harder environment in which to work, and ultimately it became impossible.

Patrick Craven

Johannesburg, 2016

BACKGROUND TO THE BATTLES TO COME

Cosatu National Congress, 2012

Cosatu was launched in December 1985 after four years of unity talks between unions opposed to apartheid and committed to a non-racial, non-sexist and democratic South Africa. According to its website, www.cosatu.org.za, at its launch it represented less than half a million workers organised in 33 unions. We currently have more than two million workers, of whom at least 1,8 million are paid up, the website states, making it among the fastest-growing trade-union movements in the world.

Cosatus main broad strategic objectives were to improve the material conditions of its members and of the working people as a whole, to organise the unorganised, and to ensure worker participation in the struggle for peace and democracy.

Its core principles included non-racialism; worker control in order to keep the organisation vibrant and dynamic, and to maintain close links with the shop floor; paid-up membership in a bid for self-sufficiency; international worker solidarity, the lifeblood of trade unionism, particularly in the era of multinational companies; and one industry, one union; one country, one federation.

Next page