An hour of freedom is worth a barrel of slops.

A law has to be fair to everybody.

Safety is all well and good: I prefer freedom.

To hold America in ones thoughts is like holding a love letter in ones handit has so special a meaning.

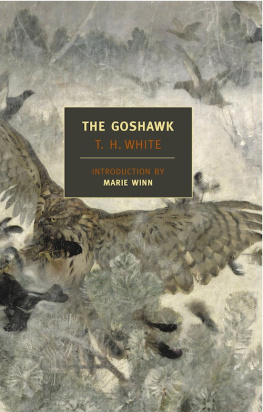

E. B. WHITE

Franklin D. Roosevelt couldnt get enough of the piece. At the suggestion of his advisor Harry Hopkins, the New Dealer turned wartime consigliere, the president of the United States took a moment away from the pressures of global war to read a July 3, 1943, Notes and Comment essay from The New Yorker. Occasioned by a letter from the Writers War Board, a group of authors devoted to shaping public opinion about the Allied effort in World War IIthe board was led by the mystery novelist Rex Stout, the creator of Nero Wolfe, the orchid-loving New York City detectivethe small item tackled the largest of subjects. Speaking in the magazines omniscient vernacular, the New Yorker author wrote, We received a letter from the Writers War Board the other day asking for a statement on The Meaning of Democracy, continuing:

Surely the Board knows what democracy is. It is the line that forms on the right. It is the dont in dont shove. It is the hole in the stuffed shirt through which the sawdust slowly trickles; it is the dent in the high hat. Democracy is the recurrent suspicion that more than half of the people are right more than half of the time. It is the feeling of privacy in the voting booths, the feeling of communion in the libraries, the feeling of vitality everywhere. Democracy is a letter to the editor. Democracy is the score at the beginning of the ninth. It is an idea which hasnt been disproved yet, a song the words of which have not gone bad. Its the mustard on the hot dog and the cream in rationed coffee.

FDR thought it brilliant. I LOVE IT! he said, with a sort of rising inflection on the word love, according to the Hopkins biographer and playwright Robert E. Sherwood. The president read the piece to different gatherings, punctuating his recitation with a homey coda (or at least as homey as the squire of Hyde Park ever got): Thems my sentiments exactly.

They were, importantly, the sentiments of the author of the Notes and Comment, the longtime New Yorker contributor E. B. White, whose writings on freedom and democracy, collected here by his granddaughter Martha White, captivate us still, all these years distant. Few things are as perishable as prose written for magazines (sermons come close, as do the great majority of political speeches), but White, arguably the finest occasional essayist of the twentieth century, endures because he wrote plainly and honestly about the things that matter the most, from life on his farm in Maine to the lives of nations and of peoples. Known popularly more for his books for children (Charlottes Web and Stuart Little) than for his corpus of essays, White is that rarest of figures, a writer whose ordinary run of work is so extraordinary that it repays our attention decades after his death.

Hence the value of the collection you are holding in your hands. White lived and wrote through several of the most contentious hours in our history, ones in which America itself felt at best in the dock and at worst on the scaffold. The Great Depression, World War II, the McCarthyite Red Scare, the Cold War, the civil rights movementall unfolded under Whites watchful eye as he composed pieces for The New Yorker and for Harpers. He was especially gifted at evoking the universal through the exploration of the particular, which is one of the cardinal tasks of the essayist. His work touched on politics but was not, in the popular sense, political, and the writings here underscore the role of the quiet observer in the great dramas of history. For White was not a charismatic speakerhe avoided the platform all his lifenor was he an activist or even a partisan in the way we think of the terms. He was, rather, a wry but profound voice in the large chorus of American life.

In the first days of World War II, in the lovely American September of 1939, after Nazi Germany launched the invasion of Poland, plunging Europe into a war that would last nearly six years, White described a day spent on the waters in Maine. It struck me as we worked our way homeward up the rough bay with our catch of lobsters and a fresh breeze in our teeth that this was what the fight was all about, he wrote. This was it. Either we would continue to have it or we wouldnt, this right to speak our own minds, haul our own traps, mind our own business, and wallow in the wide, wide sea.

That fight seems to be unfolding still in the first decades of the twenty-first century, a time when an opportunistic real estate and reality TV showman from Whites beloved New York has risen to the pinnacle of American politics by marshaling and, in some cases, manufacturing fears about changing demography and identity in the life of the Republic. We cant know for certain what White would have made of Trump or of Twitter, but we can safely say that E. B. Whites America, the one described in this collection, is a better, fairer, and more congenial place than the forty-fifth presidents. Reflecting on the Munich Pact of 1938, the agreement, negotiated by British prime minister Neville Chamberlain, that emboldened Adolf Hitler to press on with his campaign to build a thousand-year Reich, White wrote, Old England, eating swastika for breakfast instead of kipper, is a sight I had as lief not lived to see. And though Im no warrior, I would gladly fight for the things which Nazism seeks to destroy. Reading him now, at a time when so many Americans live with sights we would have lief not lived to see, is at once reassuring and challenging, for Whites America, which should be our America, is worth a glad fight.

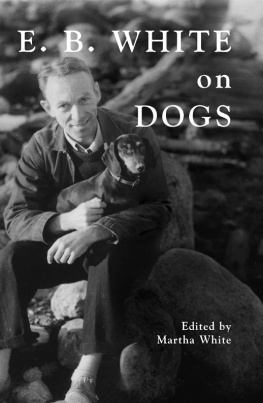

Born in Mount Vernon, New York, in 1899, Elwyn Brooks White, the youngest of six children, grew up in comfort. If an unhappy childhood is indispensable for a writer, I am ill-equipped: I missed out on all that and was neither deprived nor unloved, he recalled. His father was a successful businessman who created a secure enclave for his family in Westchester County, just twenty-five minutes from New York City. Our big house at 101 Summit Avenue was my castle, E. B. White, who was nicknamed En, wrote. From it I emerged to do battle, and into it I retreated when I was frightened or in trouble. There were summers in Maine, public school in Westchester, the warmth of a sprawling family. He was sensitive, too, from an early age. The normal fears and worries of every child were in me developed to a high degree; every day was an awesome prospect. I was uneasy about practically everything: the uncertainty of the future, the dark of the attic, the panoply and discipline of school, the transitoriness of life, the mystery of the church and of God, the frailty of the body, the sadness of afternoon, the shadow of sex, the distant challenge of love and marriage, the far-off problem of a livelihood. I brooded about them all, lived with them day by day.

Whites father, Samuel Tilly White, perhaps sensing something of his youngest childs anxious nature, wrote the lad a cheerful birthday note in 1911. All hail! With joy and gladness we salute you on your natal day, the senior White wrote. May each recurring anniversary bring you earths best gifts and heavens choicest blessings. Think today on your mercies. You have been born in the greatest and best land on the face of the globe under the best government known to men. Be thankful then that you are an American. Moreover you are the youngest child of a large family and have profited by the companionship of older brothers and sisters.... [W]hen you are fretted by the small things of life remember that on this your birthday you heard a voice telling you to look up and out on the great things of life and beholding them saysurely they all are mine.