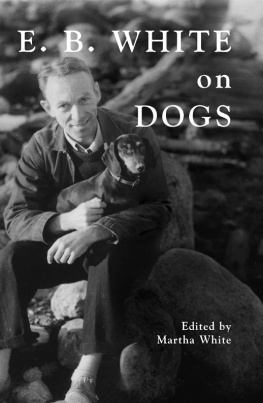

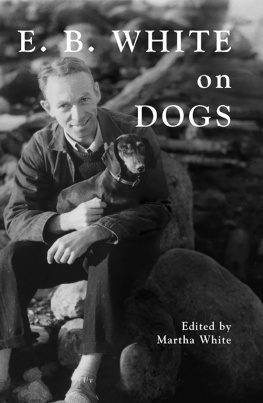

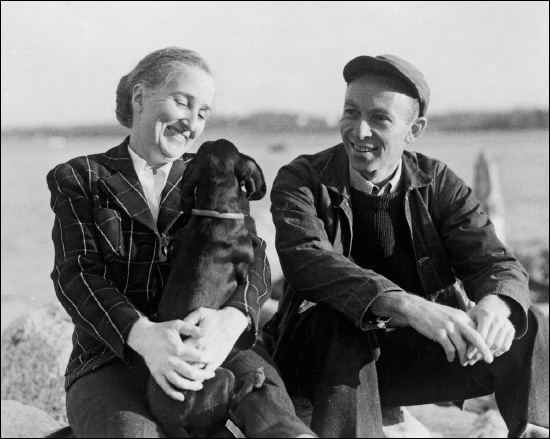

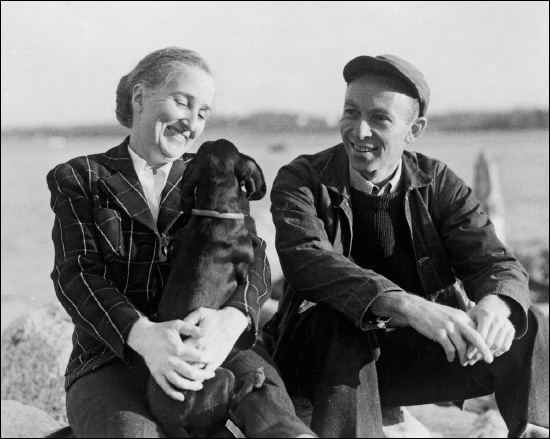

Katharine S. White, E. B. White, and Minnie in Maine

E. B. WHITE

on

DOGS

Edited by Martha White

Tilbury House, Publishers

103 Brunswick Avenue

Gardiner, Maine 04345

800-582-1899 www.tilburyhouse.com

First edition: May 2013

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Ebook: June 2013; ISBN 978-0-88448-346-5

Copyright 2013 by Martha White.

Permissions are printed on page 178.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

White, E. B. (Elwyn Brooks), 1899-1985.

[Works. Selections]

E. B. White on dogs / edited by Martha White. -- First hardcover edition.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-88448-341-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-0-88448-342-7 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. White, E. B. (Elwyn Brooks), 1899-1985 Knowledge--Dogs. 2. Dogs--Literary collections. 3. Human-animal relationships--Literary collections. I. White, Martha, 1954 Dec. 18 - II. Title.

PS3545.H5187A6 2013

818.5209--dc23

2012048622

All photographs are courtesy of the E. B. White Estate, unless otherwise noted.

Jacket front: E. B. White and Minnie, North Brooklin, Maine.

Jacket back: Minnie being interviewed in E. B. Whites New York office. Copyediting (as allowed ): Genie Dailey, Fine Points Editorial Services, Jefferson, Maine.

Photo scanning by Christine Olmstead, Before & After Photo, Brunswick, Maine.

Printed and bound by the Maple Press, York, Pennsylvania.

For my husband, Taylor Allen, with all my love

You have to watch out about dachshundssome of them are as delicately balanced as a watch.

CONTENTS

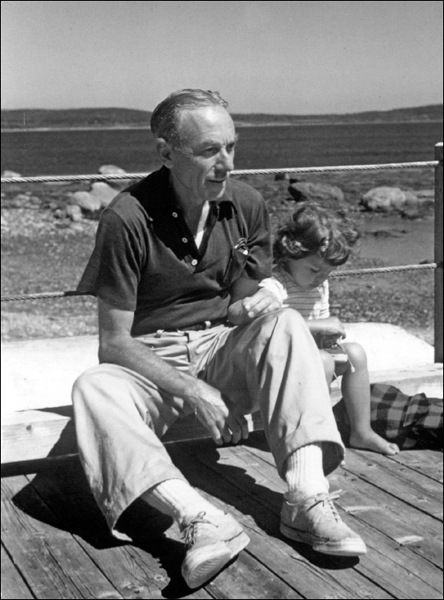

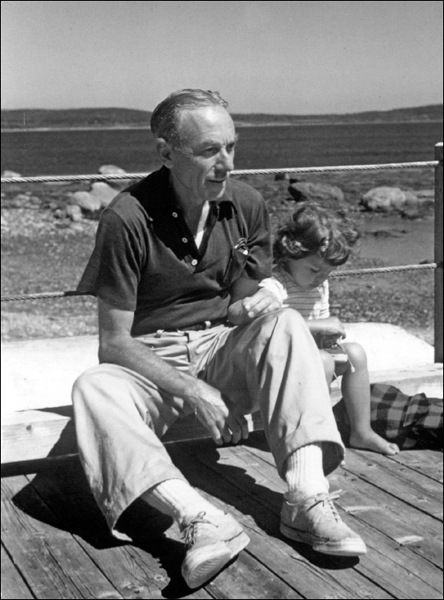

EBW and his granddaughter, Martha White

INTRODUCTION: A CHRONIC PERPLEXITY

When E. B. White wrote an obituary for a Scotty dog, an opinionated little bitch, and published it in The New Yorker in early 1932, few readers blinked an eye. They were accustomed to reading about Daisy, her likes (the iceman) and dislikes (doormen and horses), and her run-ins with the law. They already knew that her vet wore spats and called her Whitie (she was jet black), they had felt her humiliation when she was kicked out of Schraffts, and they had sympathized when she was arrested. After Daisy was run down by a Yellow Cab that had jumped the curb, Whites Obituary added his diagnosis of her curious habit of holding people firmly by the ankle without actually biting thema habit that gave her an immense personal advantage and won her many enemies. As he understood it, she suffered from a chronic perplexity, and it relieved her to take hold of something.

My grandfather also suffered from a chronic perplexity, I believe, and he spent his career trying to take hold of it, not infrequently through the literary device of his dogs. Daisy had been the sole attendant at my grandparents wedding in 1929. It was a very nice weddingnobody threw anything, and there was a dog fight, my grandfather later recalled. It was natural, then, that the same Scotty dog spoke for him, through a letter to his wife, when White wanted to tell her how happy he was that she was pregnant with his first child. He had been stewing around for two days now but was so beside himself, and hoppy that Daisy had decided to write to Katharine on his behalf.

Between E. B. Whites birth in Mount Vernon, New York, on July 11, 1899, and his own obituary in October 1985, he owned over a dozen dogs of various breedscollies, setters, lab retrievers, Scotties, terriers, dachshunds, and mongrel mixes. I was personally familiar with about half of them and I read about the others. Some appeared in his New Yorker Talk of the Town entries; Daisy and Fred (and also a goose) were interviewed on serious subjects of the day including space travel and Watergate; and many different breeds appeared in poems and sketches and even on the occasional Christmas card. In the early days of Whites comments for The New Yorker, the city dog shows were an annual topic for amusement and observations on changing styles and trends. In his Turtle Bay Diary, White wrote, The Dog Show is the only place I know of where you can watch a lady go down on her knees in public to show off the good points of a dog, thus obliterating her own.

Freds fraudulent reports from the country kept appearing long after that dachshund had died on New Years Eve, 1948 of his excesses and after a drink of brandy. He had been possessed of the vital spark for just thirteen years and four months, but his spark had a habit of rekindling whenever White was puzzling out some new perplexity. Freds dissenting nature and corrosive grin were brought to bear on Truman and Stevenson and Khruschev, and you can imagine that he had a lot to say, almost a decade posthumously, about the Russians sending a dog into space. Fred was the dishonorable pallbearer staggering along in the rear in the essay Death of a Pig, an ignoble old vigilante with a quest for truth. My grandfather often had to remind himself, He was also a plain damned nuisance.

Like my grandfather, Fred was a window gazer and a bird-watcher, peering from his vantage point on a high canopy bed on the second floor of the house in Maine. It was from that four-poster that Fred delivered his most memorable fraudulent report in the essay, Bedfellows.

I just saw an eagle go by, he would say. It was carrying a baby. My grandfather took care to explain, This was not precisely a lie. Fred was like a child in many ways.

I suspect these various dogs, in all their eccentricities, were part of what allowed my grandfather to observe and express his own childlike wonder at the natural world around him, whether in the city (Dog around the block, sniff ) or the country (I knew that as soon as the puppy reached home and got his sea legs he would switch to the supplement du joura flake of well-rotted cow manure from my boot, a dead crocus bulb from the lawn, a shingle from the kindling box, a bloody feather from the execution block behind the barn. I even introduced him to the tonic smell of coon). White also puzzled over dogs farther afield: The Russians, we understand, are planning to send a dog into outer space. The reason is plain enough: The little moon is incomplete without a dog to bay at it.

When I visited Tilbury House, Publishers, in Gardiner, Maine, to discuss this book project, it quickly became apparent that we had made a happy match. Tilbury House had taken in One Mans Meat some years ago, so they were already peddling Dog Training and A Boston Terrier and other essays with good results. Their publisher, Jennifer Bunting, had worked as my grandfathers Sunday Help for a couple of years, so she had gotten to know two of his dogs, and her offices in Gardiner were a welcome place for canines, as well. My own young golden retriever had come along for the ride. It was not until Jennifer took me around Tilbury House to introduce me to the rest of the team, howeverwhich, as it turned out, included a feisty young parrot-in-residence named Zimmy, lording it over a high filing cabinetthat the deal was sealed. As soon as I heard that parrots story, I thought, Just wait until Fred gets wind of this.

Next page