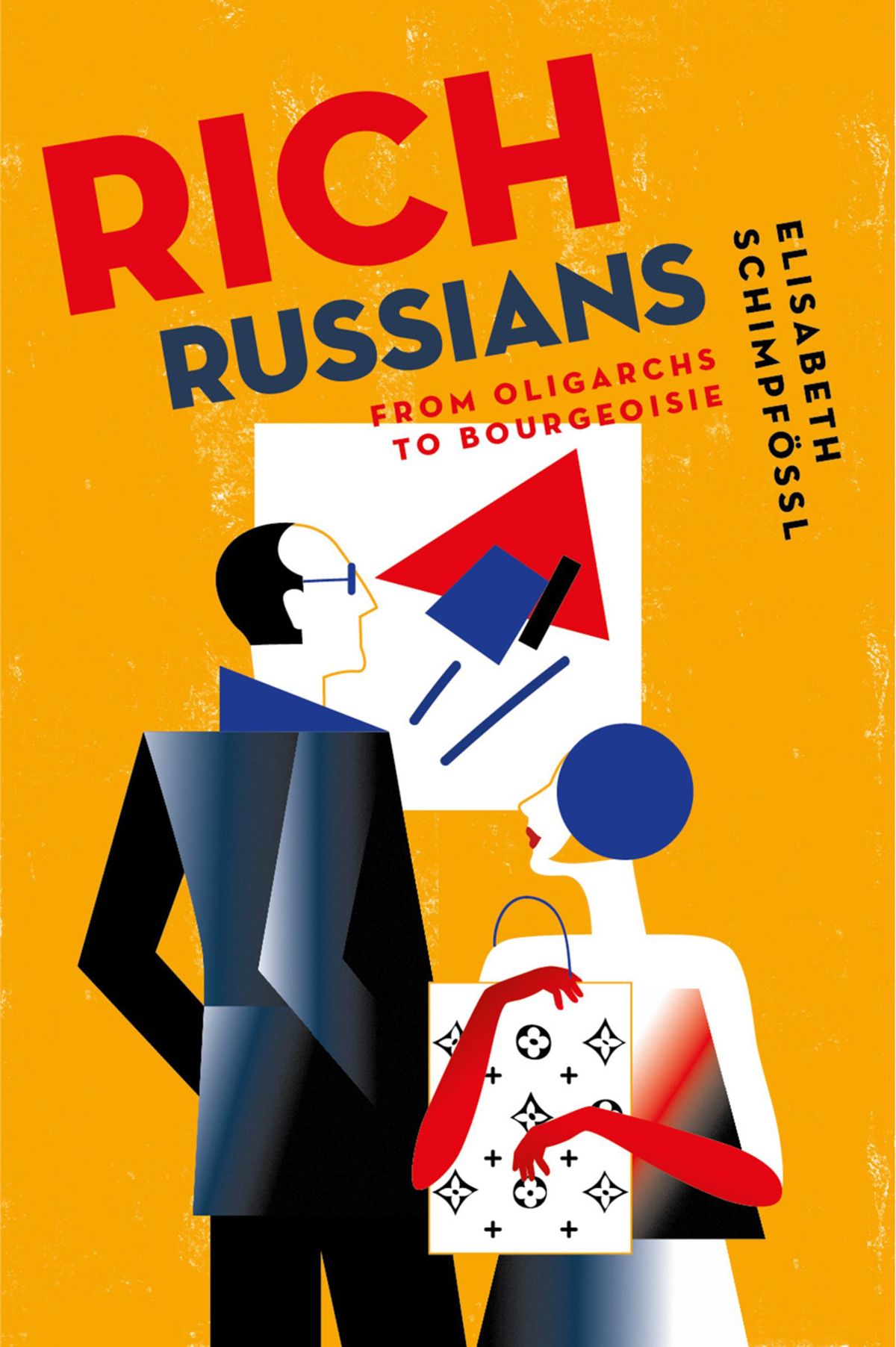

Rich Russians

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Schimpfssl, Elisabeth, author.

Title: Rich Russians : from oligarchs to bourgeoisie / Elisabeth Schimpfssl.

Description: New York : Oxford University Press, [2018] | Includes

bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017049314 (print) | LCCN 2018000033 (ebook) | ISBN

9780190677770 (Updf) | ISBN 9780190677787 (Epub) | ISBN 9780190677763

(hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Elite (Social sciences)Russia (Federation) | Social

classesRussia (Federation)

Classification: LCC HN530.2.Z9 (ebook) | LCC HN530.2.Z9 S45 2018 (print) |

DDC 305.5/20947dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017049314

Contents

THE SUMMER SUNSHINE that year was ideal for a day out at the Henley Royal Regatta, Britains most prestigious rowing competition. Well-dressed spectators who had not anticipated such a glorious day donned sunglasses with brightly colored frames handed out by people advertising The Daily Telegraph. It was hot too, and the Regatta officials fastidiously checked that the ladies had not broken the dress code by wearing dresses that did not cover their knees. In the jovial queue, people made final calls before their phones disappeared into their pockets for the rest of the day. Inside it was a quintessentially English event: impeccable riverside lawns and the Thames marked with straight rowing lanes. The races began. There was a Wimbledon-like atmosphere, but with industrial quantities of Pimms and cucumber sandwiches rather than champagne and strawberries.

I was with four young British men: George, Dave, Matt, and Harry. They were Oxbridge graduates and now worked in the corporate world. All of them were sporting their respective college rowing-club ties and blazers. We were in Leander Club, one of the worlds oldest rowing clubs, on a terrace overlooking the Thames. The water was quietly lapping against the rivers banks, its sparkle fading as the sun slowly set behind the charming houses of Henley-on-Thames. When we realized that we had been drinking for nine hours, a change of scene was suggested. Dave, a tall, cocky Old Etonian of Scottish aristocratic descent (the prominence of which he tends to inflate), remembered that a financier friend of his owns Henleys only nightclub. The strip club in the basement was a must, he said, and he sent his friend a text.

While we were waiting for the friend to reply, the four young men started swapping table-dancing stories. Many of their tales involved being ravished by high quality girls in Russia. Matt, whose physique marks him out neither as a rower nor a cox, but who is confident and brash and can be charming when required, lived in Moscow more than a decade ago. He fondly recalled those halcyon days, when pretty girls would throw themselves at him, despite his receding hairline and expanding waistline. That was just before the oil boom of the 2000s. Later, pragmatic young Russian females switched their focus from modestly well-off Western expats to extravagantly rich Russian businessmen and bureaucrats. Now married and with a good job in a large pharmaceutical company, Matt still visits Moscow as often as he can arrange for his work to send him there.

Turning the discussion to rich Russians, Matt laughingly recounted a business meeting in New York, which took place in a suite at The Pierre hotel overlooking Central Park. The billionaire host, with his sleek, slim businessman looks, could have been mistaken for a visiting Englishman, were it not for his manners. Bring me Dover sole! he ordered briskly, Matt told us. The room service waiter apologized for not having any Dover sole and suggested alternatives. The billionaire raised his voice and repeated angrily: Bring me fucking Dover sole and bring it now! He then added a long list of side dishes and the poor waiter crawled off to comply with the guests orders. As one of the top thousand richest men in the world, this pharmaceutical billionaire loves expensive cars, beautiful girlsand good food. There are some things one never gets tired of, Matt remarked.

With a glass of pink champagne in one hand and ros in the other, Dave recalled a rather peculiar RussoHenley link. Through his work, he had met the man who bought Britains most expensive house, the $180 million, 300-year-old grade II listed mansion Park Place Estate, just down the road from where we were still (just about) standing. The buyer, Andrey Borodin, is a Russian banker billionaire, who was granted political asylum in the United Kingdom in 2013 so that he could not be extradited to Russia on charges of corruption, charges which he has denied. Everybody in our corner of the terrace at Leander Club agreed that everything about the house and its owner sounded intriguing. In any event, theyre terribly nice people, Dave assured us.

George thought he might be a little out of his depth in his dealings with Polonsky; he was not sure he could fulfill his brief of helping his client save at least some of his money from Russian bureaucrats. George had never been to Russia and found it all rather too much for him. Are they all like Polonsky, he wondered?

The public perception of rich Russians in the United Kingdom is not flattering, and it is little wonder that the Western media love sensationalizing the decadence of uncouth Russian nouveaux riches: sugar daddies who splash out $2 to $3 million in an evening at Mayfair clubs; paparazzi scoops about their young mistresses shopping for diamond-encrusted Bentleys, and sometimes even mysterious deaths. Nevertheless, in answer to Georges question, they are not all like Polonsky. Harry, the fourth member of this group, from a solid middle-class background and the first in his family to make proper money, has considerable experience of working with Russians and has done business with Len Blavatnik, who was ranked number one in Britains 2015 Sunday Times Rich List.

Born in 1957 in the Soviet Union, Blavatnik emigrated to the United States in 1978 and now lives in London, from where he controls an estimated fortune of $17 billion. Blavatnik got rich on Russian oil during the privatization in the 1990s. He later pulled all of his assets out of Russia and now engages in safer activities, including philanthropy. He has funded Oxford Universitys School of Government and a new wing of Londons Tate Modern, both of which bear his name. Harry mused that if the funds had come from any number of other Russians, the university and the museum might one day have cause to regret this choice of benefactor. However, our Leander Club group agreed that Blavatnik could not really be compared to the normal Russian rich. What exactly is a normal Russian rich, I asked, but nobody was listening. Blavatnik was in a different league entirely, they said, waving away my interjection.