Published in 2018 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016

Copyright 2018 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

First Edition

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to Permissions, Cavendish Square Publishing, 243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016. Tel (877) 980-4450; fax (877) 980-4454.

Website: cavendishsq.com

This publication represents the opinions and views of the author based on his or her personal experience, knowledge, and research. The information in this book serves as a general guide only. The author and publisher have used their best efforts in preparing this book and disclaim liability rising directly or indirectly from the use and application of this book.

CPSIA Compliance Information: Batch #CS17CSQ

All websites were available and accurate when this book was sent to press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Small, Cathleen.

Title: Surveillance and your right to privacy / Cathleen Small.

Description: New York : Cavendish Square, 2018. | Series: Spying, surveillance, and privacy in the 21st-century | Includes index.

Identifiers: ISBN 9781502626769 (library bound) | ISBN 9781502626714 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Privacy, Right of--Juvenile literature. | Electronic surveillance--Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC JC596.S63 2018 | DDC 323.44820973--dc23

Editorial Director: David McNamara

Editor: Fletcher Doyle

Copy Editor: Nathan Heidelberger

Associate Art Director: Amy Greenan

Designer: Stephanie Flecha

Production Coordinator: Karol Szymczuk

Photo Research: J8 Media

The photographs in this book are used by permission and through the courtesy of:

Cover Bart Sadowski/Getty Images; p. Stephen Brashear/Getty Images.

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

Search for an Edge

Benefits of Surveillance

Surveillance Overreach

Current Surveillance and Looking Ahead

Timeline of US Surveillance

Glossary

Further Information

Bibliography

Index

About the Author

American spy Nathan Hale was executed by the British during the Revolutionary War.

CHAPTER 1

Search for an Edge

G overnment surveillance is not a new issuenot by any means. In The Art of War, a Chinese military treatise dating back to the fifth century BCE, general Sun Tzu stated, Enlightened rulers and good generals who are able to obtain intelligent agents as spies are certain for great achievements. Indeed, surveillance in the form of spying and intercepted letters and communications has been going on for centuries. Today, surveillance is obviously much more sophisticated than it used to be, involving hacking and breaches of government security. But the act of surveillance itself is not new, and a look into its history is fascinating. off about the planned assassination ahead of time, and Caesar chose to appear at the Senate anyway.

Surveillance in the Ancient World

Ancient Rome was a hotbed of surveillance activity. Politician and general Julius Caesar, for example, had a network of spies that reported to him about plots against him. He was ultimately assassinated by members of the Roman Senate, but there is speculation that his spies may have tipped him

In those days, surveillance often involved intercepted letters, given that letters were the main form of communication. Cicero, another Roman politician and a famed orator, knew that his communications were being surveyed and wrote to a friend, I cannot find a faithful message-bearer. How few are they who are able to carry a rather weighty letter without reading it.

Surveillance in the Middle Ages

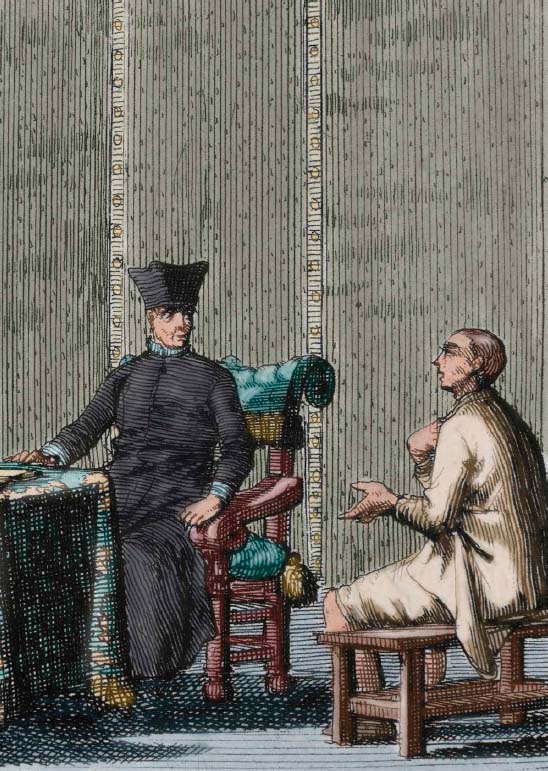

When the Roman Empire fell and the world moved into the Middle Ages, surveillance continued. The Roman Catholic Church was incredibly powerful at this point in history, and its incredibly powerful surveillance strategy supported, among other things, the Inquisition.

The goal of the Inquisition was to weed out Christian heretics . It began in France in the twelfth century, but it spread to other countries in Europe as well, notably Spain and Portugal. From there, it spread to European empires in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Inquisitors surveyed citizens they suspected of heresy and gathered information that they then used to interrogate, torture, and even sometimes execute suspects.

The Inquisition lasted until the 1820s, except in the Papal States, where it ended in the middle of the nineteenth century, and it is thought to be one of the foundations of modern surveillance. Cullen Murphy, editor of Vanity Fair and author of Gods Jury: The Inquisition and the Making of the Modern World, says that the interrogation techniques used by the inquisitorswhich at their base are similar to those used by law enforcement todayrelied on methods of surveillance to support suspicions. The Inquisition didnt, of course, have the tools that we have today for surveillance, but they had pretty good ones and they collected a lot of information. In fact, Murphy argues that the inquisitors pioneered surveillance, censorship, and interrogation, though evidence of surveillance techniques from centuries earlier would dispute that claim.

Intelligence-gathering techniques developed during the Inquisition are still used today.

Murphy acknowledges that surveillance techniques have changed, but at the core, the method remains the same. All of those things are much more advanced right now by an order of magnitude than they were centuries ago. Nowadays [surveillance] is done almost automaticallyevery time you hit the keyboard on your computer or every time you walk by a camera on the street. Surveillance is used to support suspicions and, often, interrogation. As Murphy states, An inquisitionany inquisitionreally is a set of disciplinary procedures targeting specific groups, codified in law enforced by surveillance backed by institutional power.

Surveillance in the Early Modern Era

When the Middle Ages ended around the close of the fifteenth century, the world moved into the early modern era. In England, Elizabeth I ascended to the throne in 1558, in a time of unrest in the country. England was in the midst of the English Reformation, in which the Church of England broke from the Roman Catholic Church (under the rule of Henry VIII, who wanted his marriage to his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, annulled due to her inability to produce a male heir to the throne, a request denied by Pope Clement VII in 1527), then rejoined the Catholic Church under the reign of Mary I in 1553. When Elizabeth I took the throne, she was titled Supreme Governor of the Church of England and reintroduced Protestantism into the Church of England.

Naturally, all of this back and forth with the Catholic Church created some unrest in England, which was split between Catholics and Protestants. Many Catholics considered Mary, Queen of Scots, the rightful heir to the throne of England, given that Elizabeth I had technically been declared an illegitimate daughter of Henry VIII when Henry VIIIs marriage to Anne Boleyn (Elizabeths mother) was annulled. Given Elizabeths Protestant ties, its not surprising that Catholics lobbied to have Mary take the throne. Elizabeth and Mary were first cousins once removed, and when Mary was essentially cast out of Scotland (due to her marrying a man thought to be the murderer of her second husband), she came to live with Elizabeth in England.