Published in 2019 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016

Copyright 2019 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC First Edition

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to Permissions, Cavendish Square Publishing, 243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016. Tel (877) 980-4450; fax (877) 980-4454.

Website: cavendishsq.com

This publication represents the opinions and views of the author based on his or her personal experience, knowledge, and research. The information in this book serves as a general guide only. The author and publisher have used their best efforts in preparing this book and disclaim liability rising directly or indirectly from the use and application of this book.

All websites were available and accurate when this book was sent to press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Small, Cathleen, author.

Title: Cloning / Cathleen Small.

Description: First edition. | New York : Cavendish Square, 2019. | Series:

Great discoveries in science | Audience: Grades 9-12. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018008861 (print) | LCCN 2018011728 (ebook) |

ISBN 9781502643759 (ebook) | ISBN 9781502643858 (library bound) | ISBN 9781502643971 (pbk.) Subjects: LCSH: CloningJuvenile literature. | CloningHistoryJuvenile literature. | Molecular cloningJuvenile literature. Classification: LCC QH442.2 (ebook) | LCC QH442.2 .S63 2019 (print) | DDC 660.6/5dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018008861

Editorial Director: David McNamara Editor: Jodyanne Benson Copy Editor: Michele Suchomel-Casey Associate Art Director: Alan Sliwinski Designer: Christina Shults Production Coordinator: Karol Szymczuk Photo Research: J8 Media

The photographs in this book are used by permission and through the courtesy of:

Cover Obeastsofierce/Shutterstock.com; p. 4 Look and Learn/Bridgeman Images; p. 9 Juan Gaertner/Shutterstock.com; p. 10 The Print Collector/Getty Images; p. 13 Mirko Sobotta/Shutterstock.com; p. 16 Yuri Smityuk/TASS/Getty Images; p. 19 Michael Smith/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; p. 21 Kim Jae-Hwan/AFP/Getty Images; p. 26 Lukiyanova Natalia Frenta/ Shutterstock.com; p. 29 KY Tan/Shutterstock.com; p. 33 KT Design/Shutterstock.com; p. 37 Designua/Shuterstock.com; p. 41 Rinaldofr/Shutterstock.com; p. 46 Imagno/Getty Images; p. 48 Natalie Jean/Shutterstock.com; p. 51 SPL/Science Source; p. 53 Shevs/Shutterstock.com; p. 59 Paul Clements/AP Images; p. 60 Jose Miguel Pintor Ortego /Wikimedia Commons/ File:Celia la ultima bucardo.JPG/CC BY SA 4.0; p. 64 Jiang Baocheng/VCG/Getty Images; p. 66 Kevin Horan/Aurora Photos/Alamy Stock Photo; p. 68 Wikimedia Commons/File:DNA gel.jpg/Public Domain; p. 71 Fuse Bulb/Shutterstock.

com; p. 78 Elena Pavlovich/Shutterstock.com; p. 81 Jin Liwang/Xinhua/Getty Images; p. 83 Jeffrey Markowitz/Sygma/ Getty Images; p. 86 Rosenfeld Images Ltd./Science Source; p. 88 Dominic Lipinski/PA Images/Getty Images; p. 92 Amelie-Benoist/BSIP/Alamy Stock Photo; p. 94 Noah Berger/Bloomberg/Getty Images; p. 95 Nissim Benvenisty/Wikimedia Commons/File:Human embryonic stem cells only A.png/CC BY 2,5; p. 100 Colin McPherson/Alamy Stock Photo.

Printed in the United States of America

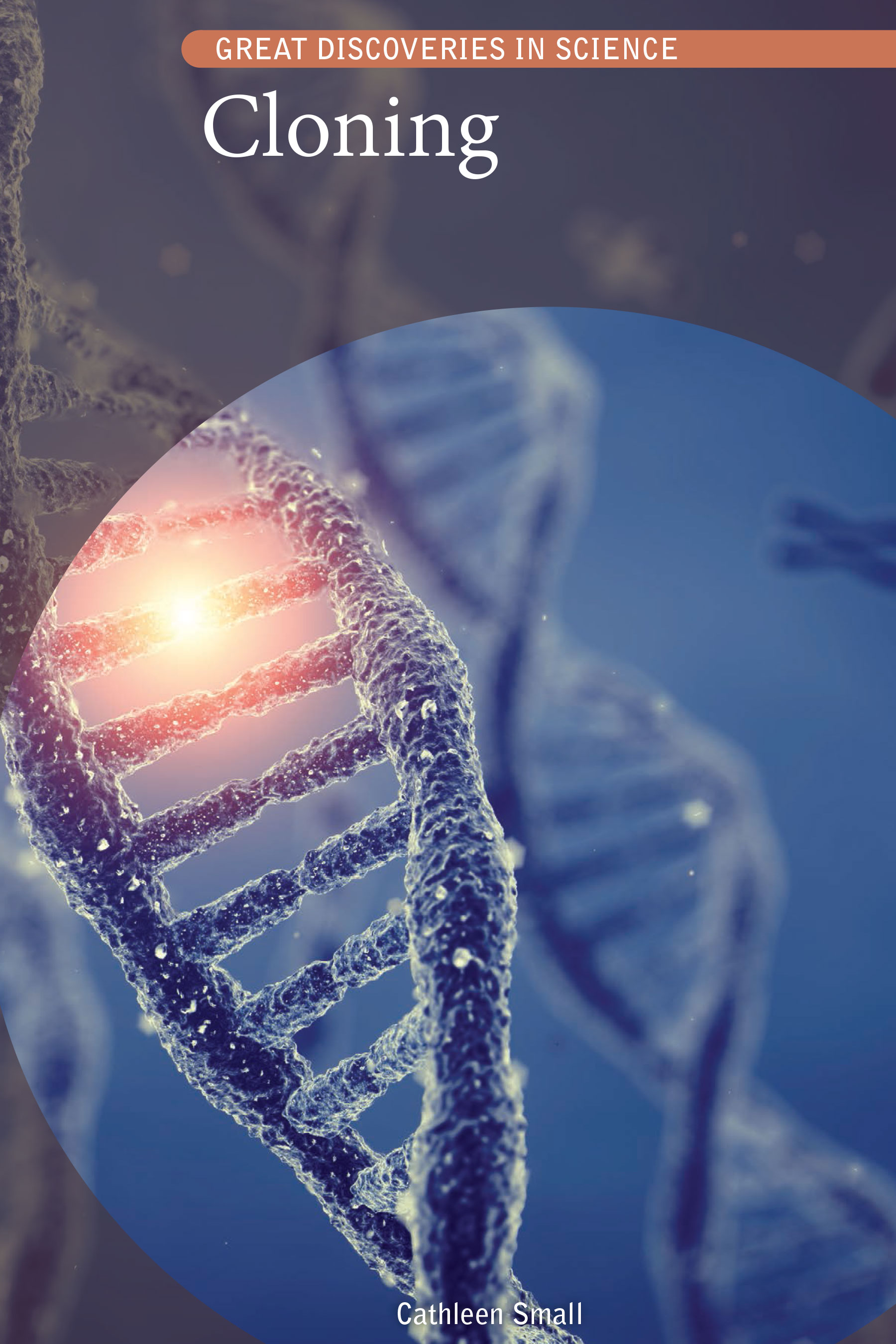

C loning used to be the stuff of science fiction. Fascinating books, television shows, and movies imagined worlds where humans were cloned sometimes for good, and sometimes for bad. In the popular book and subsequent film series Jurassic Park, for example, DNA recovered from dinosaurs is cloned and used to bring the dinosaurs back from extinction. In the books and the movies, the dinosaur cloning ends with disastrous results and becomes a cautionary tale that perhaps its not the best idea to interfere with nature without thinking about possible consequences. Cloning is also a subject in several of the Star Wars movies and spinoffs, as well as in the popular 2009 film Avatar .

But in the past century, cloning has become a realitynot necessarily in the way its depicted in movies, books, and television, but sometimes in similar ways. For example, reproductive cloning has been used to attempt to bring back extinct species, but not dinosaurs. (Scientists believe any dinosaur DNA they could recover would likely be too degraded to effectively create a clone. Also, reproductive cloning of animals requires a host mother to carry the animal and birth it, and its questionable what currently living animal would be a suitable host for a dinosaur embryo.)

Some uses of cloning actually would make for great science fiction! One of the primary areas of cloning research today is in cloning stem cells. The human body is made up of cells, but in an adult, nearly all the cells are differentiated, meaning they specialize in certain functions. For example, skin cells are differentiatedthat is, they function to create and maintain skin tissue. They do not do the job of, for example, stomach cells, which are differentiated to perform and maintain the functions of that part of the digestive tract.

Cells dont start out differentiated, though. In the very earliest stages of development, right after an egg is fertilized, the first cells that replicate in the embryo are stem cells. They are not yet differentiated, and thus, they can theoretically perform nearly any function. As the embryo develops, the cells begin to differentiate. The functions the cells do not need are turned off. For example, functions for anything other than creating and maintaining the skin are turned off in skin cells.

So, in theory, if scientists can harvest and clone stem cells, they can create stores of very versatile cells that can be used for many different functions. For example, if a person has some type of diseased tissue in his or her body, stem cells could be used to generate new, healthy tissue to repair the diseased tissue.

There are a couple of problems with this, though. First, unless the cells come from the person with the diseased tissue, the body may reject the new cells. Second, because the greatest number of stem cellsand the most versatile stem cellscome from embryos, there is an ethical debate about whether they should be used. Until recently, harvesting embryonic stem cells meant destroying the embryo, which many determined was the same as destroying a life. New developments in the field, though, have opened up possibilities for harvesting embryonic stem cells without destroying embryos.

Stem-cell cloning is at the forefront of medical research, and the possible therapeutic uses for stem cells are numerous. As research continues, scientists hope they will find ways to harvest and use stem cells that reduce the publics ethical concerns about stem-cell research and application.