Table of Contents

Landmarks

A Tragic Fate: Law and Ethics in the Battle Over Nazi-Looted Art

Nicholas M. ODonnell

Table of Contents

Copyright

Cover design by Elmarie Jara/ABA Design

The materials contained herein represent the opinions of the authors and/or the editors, and should not be construed to be the views or opinions of the law firms or companies with whom such persons are in partnership with, associated with, or employed by, nor of the American Bar Association unless adopted pursuant to the bylaws of the Association. Nothing contained in this book is to be considered as the rendering of legal advice for specific cases, and readers are responsible for obtaining such advice from their own legal counsel. This book is intended for educational and informational purposes only.

2017 by Nicholas M. ODonnell. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For permission contact the ABA Copyrights & Contracts Department, copyright@americanbar.org, or complete the online form at http://www.americanbar.org/utility/reprint.html.

Printed in the United States of America.

21 20 19 18 17 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN: 978-1-63425-733-6

e-ISBN: 978-1-63425-734-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: ODonnell, Nicholas M., author.

Title: A tragic fate : law and ethics in the battle over Nazi-looted art /

Nicholas M. ODonnell.

Description: Chicago : American Bar Association, 2017. | Includes

bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017015050 (print) | LCCN 2017015164 (ebook) | ISBN

9781634257343 (e-book) | ISBN 9781634257336 (hardcover : alk. paper)

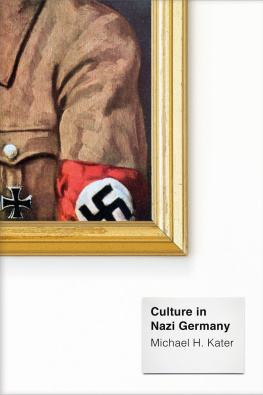

Subjects: LCSH: Art thefts. | Art theftsEuropeHistory20th century. |

RestitutionEuropeHistory20th century. | Cultural

propertyRepatriationEurope. | World War, 1939-1945Claims. | National

socialism and art. | World War, 1939-1945Confiscations and

contributionsEurope. | World War, 1939-1945Destruction and

pillageEurope. | Jewish propertyEuropeHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC K5219 (ebook) | LCC K5219 .O36 2017 (print) | DDC

940.53/18144dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017015050

Discounts are available for books ordered in bulk. Special consideration is given to state bars, CLE programs, and other bar-related organizations. Inquire at Book Publishing, ABA Publishing, American Bar Association, 321 N. Clark Street, Chicago, Illinois 60654-7598.

www.ShopABA.org

Dedication

FOR AMY

Introduction

Rue Saint-Honor, aprs-midi, effet de pluie (Rue Saint Honor, Afternoon, Rain Effect) was painted by Camille Pissarro in 1892. It shows the new Paris of Georges-Eugne Haussmanns design, with a sharp angular perspective rushing to the top left. The soft focus and muted colors mirror the subject: the wide boulevards on a rainy day. Carriages and pedestrians tread the cobblestones amidst leafless trees. It is a depiction of an ordinary day that would normally merit no commemoration. In this way, Pissarros technique also reflects the history of the painting since World War II. On the surface, the dispute is similar to many others, but digging deeper one finds a multilayered puzzle that embodies the competing narratives often at play in restitution cases: persecution, obfuscation, the murky environment of the art market after the war, and the basic tension between legal systems and who should bear the burden of resolving the competing claims.

The painting once belonged to Fritz and Lilly Cassirer, members of a family that achieved monetary success in electrical component manufacturing and later in the collection and sale of art. The Cassirers were

second-generation Jews, integrated members of the Germany of which they were citizens and supporters. They assembled a collection including numerous great works of Western art.

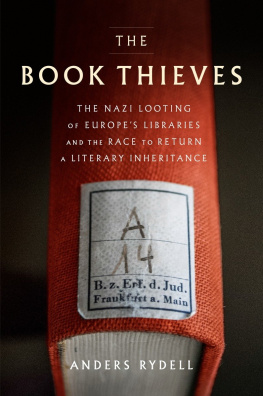

However, the Pissarro is no longer in their collection. Lilly Cassirer was targeted by a Nazi opportunist, and she sold the painting for a fraction of its value before escaping her home country. After a series of sales and donations, the painting hangs today in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, a state-run institution that exhibits a world-class collection. One wonders why the painting is in Madrid and not with the Cassirer heirs. One also wonders why the question of who ought to have the artwork only came to a head in the 1990s.

Lilly Cassirers painting met the same tragic fate as so much of the art that was stolen or purchased under duress during the Nazi occupation. The paintings murky history echoes its former owners fate and the quiet beauty of the room where it once hung. Its current possessor, the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, is a complicated figure in its own right and like many others that will be discussed below, it is a public museum whose mission is dedicated to the display of and access to great art. Unfortunately, the museums lofty mission only exists in a vacuum because the painting is in a foreign country that had no hand in the repression of the Cassirers and theft of Lillys property. The case underscores the central paradox posed by disputes in the last twenty years: It is a painting that no one disputes was stolen by the Nazis, yet it has not been, and may never be, returned to the family who owned it.

Litigation is a last resort when there is no agreement to be made. Even to consider how to array the parties and issues in litigation about Nazi-looted art is a dizzying prospect. There are items of movable personal property around the world with heirs in Europe and the United States. The countries of continental Europe and the United States take very different approaches to the varying legal issues from the procedures of dispute resolutions to the substantive laws of property. There is no easy way to reconcile the different perspectives that these myriad jurisdictions offer, and rather than unifying the dispute resolution process, what has instead emerged is a fitful lurching from one victory or defeat to the next.

How did we arrive here? The victorious Allies, the United States in particular, committed massive amounts of energy to the restitution of stolen art after the war ended. The government announced legal principles in the sight of the great tragedy that had just unfolded governing the occupation in the first instance to try to dictate who should bear the burden of proof and who held some sort of presumptive right to restitution of the thousands and thousands of dislocated objects. While those principlessome of which turned into laws, some of which guided judicial interpretationscast a long shadow into the future, actual private party disputes were relatively rare for the better part of fifty years. After the war, the world was putting itself back together but was becoming entrenched in the new Cold War. It was not until the collapse of the Soviet Union and the breathing room created by that development in world affairs which afforded the various countries a look backwards with fresh eyes and slowly began a comprehensive effort to assess how stolen art ought to be restituted or not.

This book will address comprehensively those cases that have ended in litigation in U.S. courts. While the impact of dispute resolutions in other countries is of critical importance and relevance, this is not a treatise on those foreign processes. Litigation in the United States is based on neutral principles that are not necessarily related to the Holocaust, but the process does reveal a great deal about the policies that the United States has wrestled with for more than seventy years, policies that are interesting to compare with those of other affected countries. To try to recover personal property requires bringing common-law claims such as conversion (the unauthorized control over anothers property), replevin (a legal action to compel the return of property in ones possession, often in tandem with a conversion claim), or arguments about bailment (the conditions under which one holds property for another). However, these torts usually have statutes of limitations of three years or so. Sometimes there are conditions under which those deadlines can be delayed and sometimes not.