Published by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

1998 by Stuart A. Schlegel

All rights reserved

Designed by Erin Kirk New

Set in 12 on 15 Centaur by G&S Typesetters

Printed and bound by Maple-Vail

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for

permanence and durability of the Committee on

Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the

Council on Library Resources.

Printed in the United States of America

02 01 00 99 98 C 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Schlegel, Stuart A.

Wisdom from a rainforest : the spiritual journey of an anthropologist / Stuart A. Schlegel.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8203-2057-9 (alk. paper)

ISBN for digital edition: 978-0-8203-4958-9

1. Tiruray (Philippine people)Social conditions. 2. Tiruray (Philippine people)Psychology. 3. Tiruray (Philippine peopleEthnic identity. 4. DeforestationPhilippinesMindanao Island. 5. Rain forest ecologyPhilippinesMindanao Island. 6. Rain forest conservationPhilippinesMindanao Island. 7. Mindanao Island (Philippines)Politics and government. I. Title.

DS666.t6S36 1998

959.97dc21 98-7608

This book is dedicated to

Len,

who lived so well and died so young.

And to

Will,

who taught us all to be strong.

Things fall apart; the center cannot hold:

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world...

Surely some revelation is at hand...

William Butler Yeats, The Second Coming

Prologue

This book is a love story.

In the middle of a dark night in July 1967, deep in a Philippine rainforest, I realized that my son Len, sleeping beside me on the bamboo slat floor of my tiny house, was sick. The heat of his feverish body had awakened me. Rain, which had begun the day before, pounded loudly against the grass roof, but I could still hear him moaning. Len was only six years old, and his motherwho knew much more than I did about sick childrenwas far away. But I knew that he was too hot. I woke him up and gave him an aspirin with a little water I kept by the sleeping mat. As the night went on he became hotter and hotter. I lit a kerosene lamp, climbed out of the mosquito net we were sharing, and poured more cool water. I sponged off his arms and legs, hoping that by cooling them I might bring down the fever. Perhaps it helped; I couldnt tell. Len kept moaning and I waited impatiently for morning, my mind filled with dark apprehension.

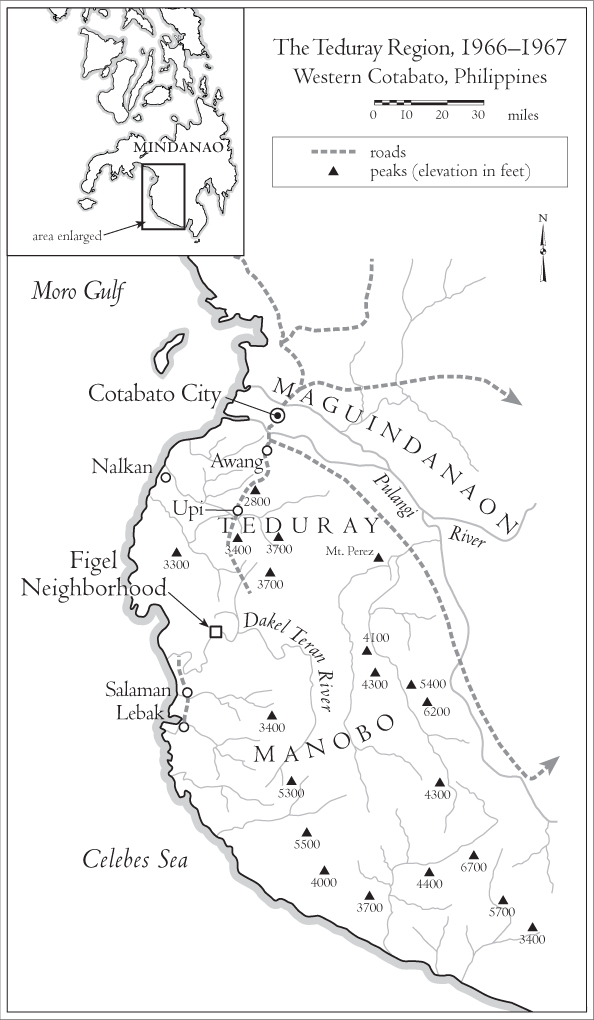

We were in a place called Figel, a small Teduray settlement alongside the Dakel Teran River on the island of Mindanao. Len and I had walked in the day before, wading across the wide river numerous times. It was a long, hard, full days trek into the heart of the forest.

Morning finally came andat lastI heard the playing of gongs which greeted each sunrise in Figel. I saw several Teduray friends up and stretching in the morning mist, their sleeping sarongs cowled over their heads against the damp coolness of the new day, and I called for them to come over and look at my son. By then he seemed to be much worse. He had lost control of his bowels and bladder, and he was obviously seriously ill.

Several women and men discussed the situation among themselves. They saw my fear and concern, and some of the men said that they would leave immediately and carry Len out to the coastal town of Lebak, where there was a large plywood factory that had my kind of doctor. Normally the trail to Lebak involved fording the winding river about a dozen times as it snaked its way to the sea. But I knew that would be impossible now: the nights hard rain had swollen the river, removing any hope of crossing it. It was strong and swift and twice its usual armpit depth. People never tried to go to town under such conditions. But my Teduray companions saw that I desperately wanted my son to see the coastal doctor, and knowing this touched a deep chord in them, in their understanding of how life should be lived. The Teduray I knew in Figel never ever took someones wants or needs lightly. They were willing to risk their lives to take him there.

They would attempt this unimaginably dangerous trip even though they were certain that Lens illness was due to his having unintentionally angered a spirit. The Figel people had no concept whatsoever of germs, or even any awareness of what my kind of doctor did, and although no one said anything, I knew they had informed one of the Figel shamans, who would litigate with the offended spirit as soon as possible to effect a cure.

One of the men quickly cut down two six-foot lengths of bamboo from a nearby grove and hung a sarong between them. We then put Len, who seemed to me barely conscious, in this makeshift stretcher. The trek would be agonizingly slow with the river so treacherous; no one would ever attempt it unless forced to by an emergency. But within twenty minutes of the gongs announcement of the dawn, we were off. Our little groupsix Teduray men, Len, and memade its way, deliberately and torturously, along the full length of the flooded, furious river, clinging to its banks. Fear for myself and my friends safety now joined my anxiety about Lens condition. In many places the men carrying Len had no firm footing and, their muscles taut and glistening with sweat, were forced to grasp exposed tree roots or shrubs as the river crashed by just below them. The going was slow. Although we stopped for very few breaks, the day passed all too quickly and we were still far from the coast.

After sundown darkness filled the forest, but our little band struggled on. There was a half-moon for part of the night, but not much of its light penetrated the canopy of high trees to reach us on the forest floor. When the night became too dim and the darkness too dangerous we paused and made torches of tree resin applied to the end of short sticks. As we continued along the river banks, we held the torches high with our free hands so that we could see where to put our feet and grasp for firm handholds.

I stumbled alongside my sick and frightened son trying to comfort him, awkwardly keeping up as best I could with these men who had spent their whole lives on this river and in this forest. I put cool cloths on his forehead and spoke to him whenever we stopped for a break or to switch litter bearers.

The trip was a twenty-hour nightmare of physical exertion and danger. We crawled along the river through most of the night, resting only occasionally for a few short momentswhich seemed to refresh the Teduray but which did little for my fear and heartache. I knew the breaks in the pace were necessaryit was incredible that these men didnt need more of thembut Len seemed to be getting hotter and weaker, and the horrible possibility that he might not make it weighed on me.

Just as morning was about to dawn we finally dragged ourselves out of the forest and reached the road that led to Lebak. I found someone who had a jeep, and he agreed to take Len and me into town, while my Teduray friends rested a few hours before starting back to Figel. At the plywood factory, the doctor checked Len carefully and told me that my son was not really all that critical, that he had a kind of viral flu that produced nasty symptoms but was not actually life-threatening. My feeling of relief at that welcome news soaked into every cell of my weary mind and body. I remember the moment clearly still today.