RAINFOREST

RAINFOREST

DISPATCHES FROM EARTHS MOST VITAL FRONTLINES

TONY JUNIPER

COLOUR IMAGES BY

THOMAS MARENT

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

Profile Books:

3 Holford Yard, Bevin Way

London WC1X 9HD

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright Tony Juniper 2018

Views expressed in this book are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the policies or perspectives of any organisations that he is or has been affiliated with, including the WWF.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

e-ISBN 978-178-283249-2

Set in Adobe Garamond Pro and BentonSans to a design by Henry Iles

Cover photo: Danum Valley, Sabah, Borneo Thomas Marent

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

RAINFOREST MATTERS

In the spring of 1990 Friends of the Earth placed an advertisement in New Scientist magazine inviting applications to lead the organisations tropical rainforests campaign. Id done some campaign work with the International Council for Bird Preservation (now BirdLife International) trying to save the worlds most threatened parrots from extinction, had a couple of science degrees and a passion since childhood for wildlife. It seemed like the job me, so I applied. To my delight I was offered the role and six weeks later reported for duty.

Friends of the Earth operated out of a shabby office building in a then run-down part of Shoreditch, close to the City of London. It was a 1950s building, built on a V2 bombsite amid a row of Victorian warehouses. It struck me as a fitting location from which to wage the campaign for these wonderful ecosystems. First thing that Monday morning I met my new team to talk about strategy and where we needed to focus our efforts. There were boxes of papers everywhere, covering every conceivable subject linked with tropical forests. I was told how the archive was organised and how it was maintained. Then my new boss, Campaigns Director Andrew Lees, took me up onto the roof to tell me roughly what he had in mind.

Andrew was a charismatic and gritty figure, oozing fighting spirit. He smoked cigarettes and consumed a large mug of sweet black coffee while giving me a precis of the campaign to date, and where he thought it should head next. He wanted to raise political pressure for more action and that would come from a combination of research, media coverage, lobbying and public backing for our goals. These included ending unsustainable tropical timber imports to Europe, changing the policies of the World Bank (which had funded a lot of tropical forest destruction) and altering the practices of multinational companies, such as those in the oil and gas sector that were entering indigenous territories in the Amazon. There was also an ongoing campaign on Third World debt, which had been identified as one of the underlying economic drivers of the problem.

Wed need to raise the money to do all this, he explained, and build up the capacity of the Friends of the Earth International network, so that campaigners in the rainforest countries were better equipped for the epic struggle that lay ahead.

Is that all? I said. No, replied Lees. But its enough to be getting on with. Id better get started then, I said, and so began my career as a campaigner for the tropical rainforests.

Ive been at it ever since.

* * *

Back in 1990 awareness about the plight of the tropical rainforests was growing fast in relation to the threats to indigenous people and wildlife, especially across the Amazon. There, native societies were being driven into oblivion, their languages, culture and ways of life being lost forever, and so too were many species of animals and plants, including untold numbers still to be described, haemorrhaging into extinction right before our eyes.

There was far more limited awareness of the rainforests hugely important role in combatting climate change (a phrase then yet to reach general currency), through the absorption of carbon dioxide. A few months after I joined the team we issued a report on the scale of climate-changing emissions caused by deforestation. Having worked with leading climate change and deforestation experts, our estimate was that about a fifth of emissions were then being caused by tropical rainforest destruction a figure confirmed later by better-resourced research agencies. The report got hardly a mention in the media.

And there was even less popular knowledge or indeed much available scientific research of the role of the forests in replenishing oxygen, or driving the circulation of fresh water, and how deforestation in South America might impact on the frequency and intensity of droughts in places as far afield as North Americas Great Plains, Africa and Europe. In short, we didnt know the half of it. Rainforests were far more important than we had imagined.

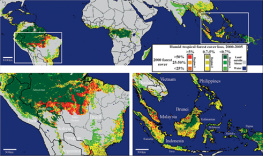

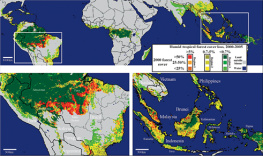

What we did know, though, was that rainforests were already in crisis. The scale of forest loss in some regions was already extreme, in south-eastern Brazil and West Africa, for example, and was indicative of what could soon lie ahead for other tropical rainforest regions. During the 1970s scientists had for the first time begun to compile comprehensive data sets on forest losses and in 1981 the UN published its findings in its first Tropical Forest Resources Assessment Project, detailing the huge scale of forest loss then taking place. In 1990 a more sophisticated analysis using satellite data estimated that the compound rate of tropical forest loss was running at nearly 1 per cent per year.

That trend, if it remained static, would see the disappearance of all of the tropical forests within a century. There was a real sense of urgency, increasingly high stakes, and with that a huge responsibility to succeed. In the way of success, however, lay some very deep challenges. Not least of these were the rapidly growing populations of many rainforest countries and the related need, as many political and business leaders saw it, to expand economic growth so as to help ensure the expanding numbers of people didnt live in poverty.

Against this backdrop my Friends of the Earth predecessor Charles Secrett had in 1984 launched the worlds first campaign to slow down and halt the destruction. In the pages that follow I tell the story of the battle for the rainforests, what I have seen at the frontlines, what has worked and how progress has sometimes been made. We start, though, with more on why these rainforest ecosystems are so important and extraordinary, and the crucial roles they play in the rise of truly twenty-first-century challenges water security, climate change and conserving the Earths staggering natural diversity.

Tony Juniper, Cambridge, 2018

RAINFOREST A CLUE IN THE NAME

How tropical rainforests make clouds and recycle water, sustaining farming far away from where they stand