Published in 2003 by

Routledge

29 West 35th Street

New York, NY 10001

www.routledge-ny.com

Published in Great Britain by

Routledge

11 New Fetter Lane

London EC4P 4EE

www.routledge.co.uk

Copyright 2003 by Taylor & Francis Books, Inc.

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 0-415-92979-2 (hb)

ISBN 0-415-92980-6 (pb)

Foreword

When the People Lead

by David Helvarg

I was traveling through Guatemalas Alto Plano in the bloody winter of 1980. We had just hitched a ride on a truck out of the town of Nebaj, where three days earlier the army had killed eight Mayan Indians, shooting into a crowd of demonstrators in the town square. What did they want? I asked one of the troops whod opened fire on them. Who knows? he said in Spanish. They dont even speak our language.

As we drove along the dark switchbacks of the steep unpaved road we came upon a convoy of open trucks full of Indian campesinos guarded by army troops carrying Israeli assault rifles and wearing black woolen Balaklavas to hide their identities. Their recruits were the Mayan army of labor who would be used as seasonal pickers in the cotton fields of the Atlantic lowlands. They would have a months long reprieve from the brutal repression in the mountains only to face pesticide poisoning and back-breaking wage slavery harvesting an agro-export crop that at the same time was eroding and drying out what had once been lush coastal rainforest.

It was during the five years I covered civil and highly uncivil conflicts in Central America, amidst the bombs, bullets, mutilated death-squad victims, coffee fincas, DDT-scented cotton fields, crowded barrios, and burned-over forests, that I came to appreciate the close connections between issues of war, development, population, poverty, and natural resource management.

Trouble in Paradise , J. Timmons Roberts and Nikki Demetria Thanoss fast-paced, complex, challenging, and important work, takes me back to numerous scenes I encountered while covering Central Americas wars, the U.S. border region, and, more recently, environmental conflicts throughout Latin America.

Roberts and Thanos have traveled the muddy forest trails as well as the diesel- and dust-choked barrios of our hemisphere to track the issues and connections that link the impoverishment of many of Latin Americas people with the degradation of their environment. They provide social and historical context from the post-Columbian colonization and plunder of South America to the most recent conflicts over indigenous rights in the globalized Latin markets of the early twenty-first century. While not denying the possibility of change and betterment, neither do they insult us with easy answers to complex questions about resource development, democracy, and sustainability.

Mostly theirs is an exploration of biological and social complexity. In setting the scene they argue, To become sustainable, Latin America needs real democracy to create the leverage for its citizens to demand a cleaner environment and the services they need to survive.

The linkage between democracy and environmental protection is critical and dynamic. It could be argued that democracy is a precursor to significant environmental change and yet, in visits to places as diverse as Poland and South Korea, Ive also seen how militant environmental protests have set the stage for popular democratic uprisings.

Roberts and Thanos point out the contradictions between U.S. and other developed nations demands that Latin America protect its forests and biodiversity while at the same time, through multilateral lending agencies, imposing economic austerity that denies Latin American governments the means to pursue these goals. The North demands repayment of huge debts built up under a generation of (U.S.-backed) military dictatorships while ignoring how debt repayment has become a driver of the short-term liquidation of Latin Americas natural resource base.

In expanding on these and other themes, the authors take us on a bottom-up tour of the post-NAFTA free-trade environment along the United StatesMexico border. They guide us into the war-ravaged and deforested heartland of Central Americas chemically dependent green revolution and Cubas forced shift to organic farming. They explore the urban heat of a continent 75 percent of whose people are now city-bound and take us across the vast Amazon basin, whose diversity is both human and biological and whose problems are as convoluted as a mating ball of anacondas. They explain the Fourth World of indigenous peoples who are using every available tool from arrows to the Internet to reclaim their power as users and protectors of the natural environments that sustain them. And finally they give us a practical vision of an engaged civil society at the local, regional, and global level that must come to fruition if the eco-crisis of Latin America is to be reversed.

Its an expansive but well-documented journey that frequently recalled my own moments and memories and confirmed many of their key observations. After describing the state of pollution and poverty along the border the authors quote a UN report that suggests that the maquiladora assembly industry that defines NAFTA production on La Frontiera specializes in cheap labor and does not constitute a motor for sustainable growth with more social equity. I recall a visit to a computer chip assembly plant in Tijuana that had a production line made up entirely of maquila girls, young women in industrial smocks working nine-hour shifts. With their smaller hands, theyre much more dexterous workers than the men, the plant manager explained to me with a straight face (they were also paid less and were harder to unionize at the time). Years later I heard the same comment from a supervisor at a factory farm in rural Maine where over 150 Mexican women work the egg-packing line. The inequalities that global capital imposes on Latin America seem to provide a secondary benefit to corporations by driving cheap immigrant labor into both traditional and formerly unionized sectors of the U.S. economy. At the same time free-trade environmental standards are neither harmonized nor predictable. At that factory farm in Maine, eggs bound for Canada are separated out for a more rigorous health inspection process than those headed to U.S. store shelves.

And for those imagining hardy Latin peasants getting their own fresh eggs from the chickens in the yard, Latin America, Roberts and Thanos point out, is the most urbanized part of the developing world, with 380 million of its 507 million residents now living in cities, including fifty-two cities with populations of over 1 million.

Ecology in the Third World, they quote a Brazilian expert, begins with water, garbage, and sewage.

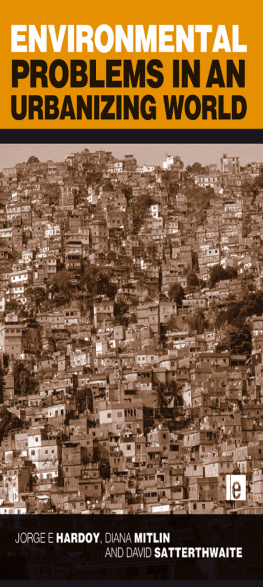

Certainly, traveling through the Ciudades Perdidos, the lost unnamed tin and junk wood barrios on the sprawling edge of Mexico City, the hemorrhaging heart of a nation rapidly running short of the essentials of life, including water, light, and breathable air, it is easy to despair. Nor has my faith in urban restoration been inspired by the sight of children picking through burning mountains of garbage on the edge of Tegucigalpa, Honduras, or armored tanks guarding the entrances to the hillside favelas we visited during the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio, or El Alto, the cold-blasted stone hut barrio of displaced Indians that sits above La Paz, Bolivia. Here at thirteen thousand feet above sea level it is the poor who live on the heights while the rich live down below in the warmer, thicker air.