Table of Contents

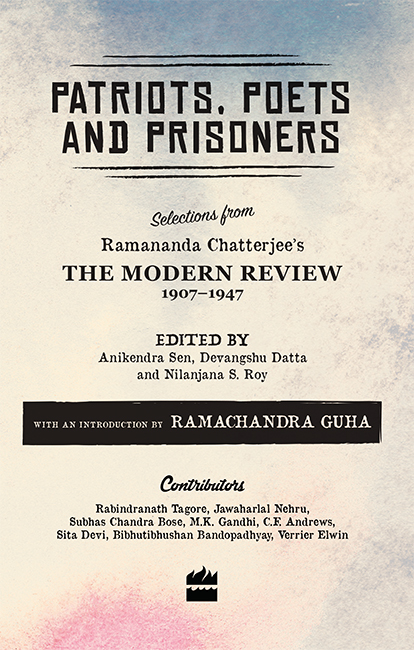

PATRIOTS, POETS AND PRISONERS

SELECTIONS FROM RAMANANDA CHATTERJEES

The Modern Review, 19071947

Edited by

Anikendra Sen

Devangshu Datta

Nilanjana S. Roy

With an introduction by Ramachandra Guha

HarperCollins Publishers India

To Independent India and to liberal values, two things

that Ramananda Chatterjee fought for

Contents

J ournals of opinion have had a disproportionate impact in shaping the public discourse of the modern world. Think, for example, of Les Temps Moderne in France, National Interest and The Nation in the United States, the New Statesman and The Spectator in the United Kingdom. These magazines sold far fewer copies than daily newspapers, yet had a far greater influence on politicians, civil servants, social activists and scholars.

The first Indian equivalent of Les Temps Moderne, the New Statesman, etc., was The Modern Review. Founded in 1907 by Ramananda Chatterjee, The Modern Review quickly emerged as a vital forum for the nationalist intelligentsia. It carried essays on politics, economics and society, but also, being run by a Bengali, poems, stories, travelogues and sketches.

Modern Review was the stable-mate of Prabasi, which was published in Bengali and catered exclusively to one linguistic group. As a vehicle for bilinguals from all parts of the subcontinent, the monthly Modern Review appeared, naturally, in English. While being broadly nationalistic it did not hold a brief for any particular political party. The first feature meant that it could act as a genuinely all-India forum; the second that it stood apart from party journals concurrently run by the Congress, the Muslim League, the Hindu Mahasabha, the Communists, and the Scheduled Castes Federation.

In a fine scholarly essay on the history of The Modern Review, the literary historian, Margery Sabin, explores the questions that most preoccupied the journals editor. Ramananda Chatterjee, she writes, sustained in his own voice and sponsored in the voices of his contributors fundamental and continuing questions about Indias past, present, and future: What constitutes the authentic Indian past? What foreign influences in the present should India welcome or shun? What directions for the future would allow India to become modern without betraying its own identity?

Sabin also analyses how Chatterjee skilfully negotiated his way through the mire of repressive colonial laws restricting press freedom. Since outright calls for Indian independence could attract prosecution on grounds of sedition, Chatterjee often quoted British statesmen in praise of liberty and national emancipation. Drawing on a well-stocked library and his own wide learning, a plenitude of English voices from the past could be summoned to indict British rule without the editor risking a sentence of his own.

Among the most famous articles published in The Modern Review was The Call of Truth, by Rabindranath Tagore, which appeared in the issue of October 1921. Tagore had recently returned from a long trip abroad, where he had gone to raise money for his new university in Santiniketan. While he was away, Mahatma Gandhi launched his Non-co-operation movement, urging Indians to boycott state-run schools, colleges, and law courts, organize bonfires of foreign cloth, and court arrest in doing so. Reading the news from India, Tagore was dismayed. As he wrote to C.F. Andrews from Chicago on 5 March 1921: What irony of fate is this that I should be preaching co-operation of cultures between East and West on this side of the sea just at the moment when the doctrine of non-co-operation is preached on the other side?

Later that year, Tagore returned to India, had long conversations with Gandhi in Calcutta, but remained unpersuaded about non-co-operation and its methods. When he decided to go public with his criticisms, he chose The Modern Review as his outlet. In his recent travels in the West, said Tagore, he had met many people who sought to achieve the unity of man, by destroying the bondage of nationalism. He had watched the faces of European students all aglow with the hope of a united mankind. Then he returned home, to be confronted with a political movement suffused with negativity. Are we alone to be content with telling the beads of negation, asked Tagore, harping on others faults and proceeding with the erection of Swaraj on a foundation of quarrelsomeness?

Gandhi replied in equally spirited tones, albeit in his own journal, Young India. The Non-co-operation movement, he said, was a refusal to co-operate with the English administrators on their own terms. We say to them, Come and co-operate with us on our terms, and it will be well for us, for you and the world. A drowning man cannot save others. In order to be fit to save others, we must try to save ourselves. Indian nationalism is not exclusive, nor aggressive, nor destructive. It is health-giving, religious and therefore humanitarian. India must learn to live before she can aspire to die for humanity. The mice which helplessly find themselves between the cats teeth acquire no merit from their sacrifice.

(Some years later, Tagore wrote another critique of Gandhi in The Modern Review, this time deploring the cult of the charkha. The debates between Tagore and Gandhi in their entirety have been published in The Mahatma and the Poet, edited by Sabyasachi Bhattacharya, who has also provided a useful introduction. This is a book that every thinking Indian should possess. It is published by the National Book Trust, which means that every Indian can afford it, but few would know where to find it.)

Another celebrated essay published in Ramananda Chatterjees journal was an auto-critique. In its issue for November 1937, The Modern Review carried a profile of the Congress president, Jawaharlal Nehru. The profile was not wholly flattering; it spoke, for example, of Nehrus intolerance of others and a certain contempt for the weak and inefficient. It noted that his conceit was already formidable, and worried that soon Jawaharlal might fancy himself as a Caesar.

The essay was written under the pen-name of Chanakya. There was much speculation as to who the author might have been. It appeared to be a critic of the Congress president, possibly a critic of the Congress party as well. Then it was revealed that the author was none other than Jawaharlal Nehru himself.

That Tagore would criticize Gandhi in its pages, or that Nehru would anonymously criticize himself here, were marks of how significant The Modern Review was to public discourse in late colonial India. The magazine was vital to intellectual debates as well. It was in The Modern Review that the sociologist, Radhakamal Mukerjee, published his early pioneering essays on environmental degradation in India; and it was to The Modern Review that the anthropologist Verrier Elwin sent his first reports from the Gond country. Among the magazines other contributors was the distinguished historian Jadunath Sarkar.

As a platform for debate and discussion among Indias finest minds and its most public figures, The Modern Review played a major part in the process of national awakening. Education, the rights of women, the relations between religions and castes, Indias place in the world these extremely important subjects were all intensively discussed in its pages. Significantly, the coming of political independence dealt a body blow to the journal. For its perspective was forward-looking, the nurturing of reforming sensibilities among the men and women who would one day come to rule India. When the former freedom fighters slipped comfortably into the chairs in the secretariat, the magazine seemed to have lost its bearing.