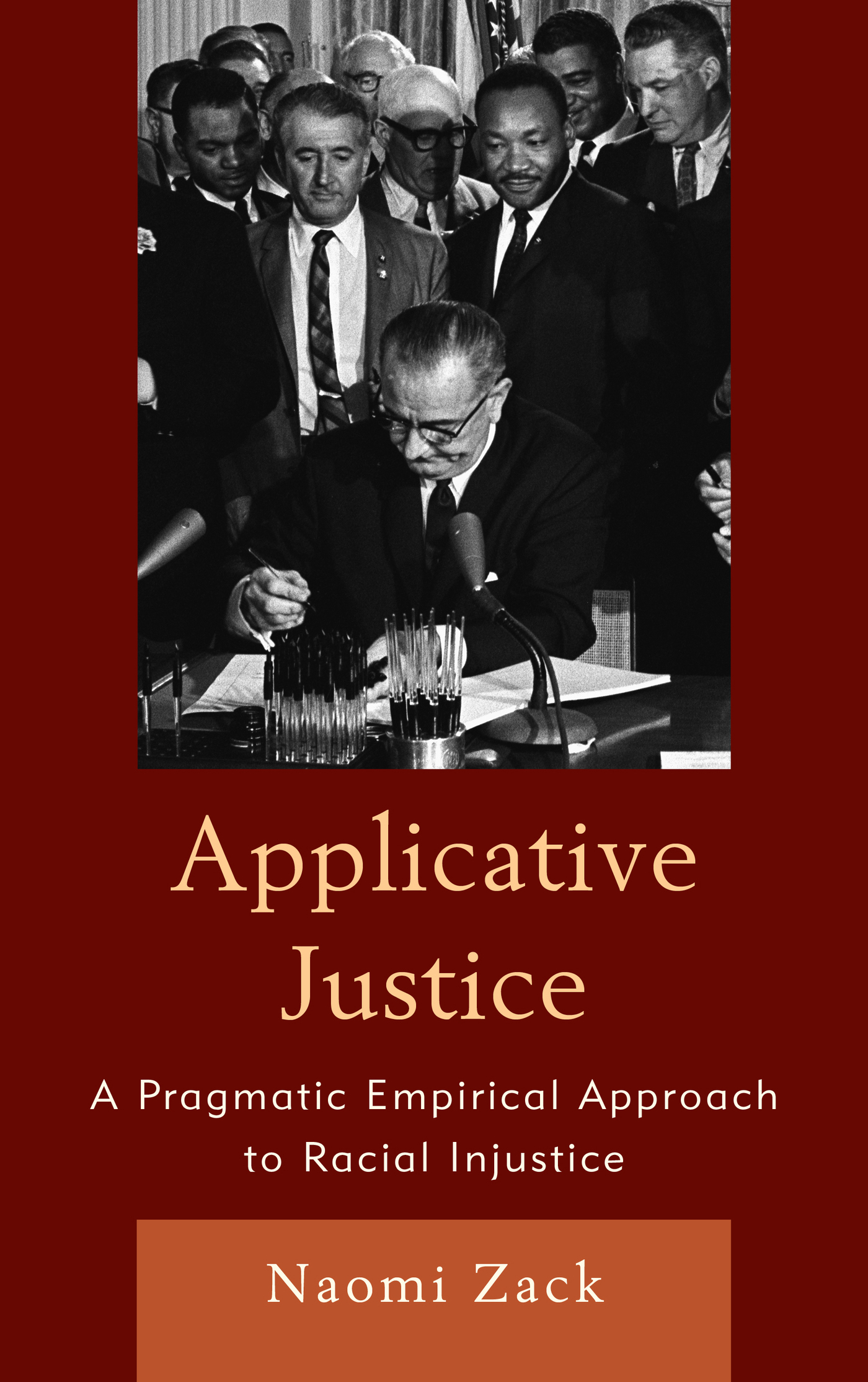

Applicative Justice

Applicative Justice

A Pragmatic Empirical Approach to Racial Injustice

Naomi Zack

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2016 by Rowman & Littlefield

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Zack, Naomi, 1944

Title: Applicative justice : A pragmatic empirical approach to racial injustice / Naomi Zack.

Description: Lanham & Rowman Littlefield, 2016 | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015039250| ISBN 9781442260009 (cloth : alkaline paper) | ISBN 9781442260023 (electronic)

Subjects: LCSH: Justice (Philosophy) | Equality--Philosophy. | Equality before the law.

Classification: LCC Classification: LCC B105.J87 Z34 2016 | DDC 320.01/1--dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015039250

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

To Alex, Bradford, Jessica, Coco, and Winnie

Why then do most philosophers refuse

to think about injustice as deeply and subtly as they

think about justice?

Judith Shklar, The Faces of Injustice

Preface

The story of how President Lyndon B. Johnson came to sign into US law the Civil Rights Act of 1964 has many anecdotal sidebars and conflicting accounts, which can be distilled into these three facts: He was a Southerner, from a culture that would be considered unjustly racist today. He was a master politician who orchestrated many complex political gyrations in getting the act passed. The act was passed. That entire struggle toward written justice, the importance of the law itself, and the disappointment of subsequent events that have not lived up to either its letter or spirit is a symbol of what motivates this book, which is its real subtitle: How we can make sense of the combination of good intentions, bad intentions, self-serving grasps at power, good laws, and bad practices, as all part of the same political life, in our time and earlier, both in general and down to small detail? Of course, I have chosen to avoid a subtitle more suitable to the seventeenth century, and described the project of this book as A Pragmatic Empirical Approach to Racial Injustice. My approach is pragmatic by focusing on the silent cry for help from many quarters that has not so far been answered, and it is pragmatic in drawing on the philosophical tradition of pragmatism.

For several years, a copy of Bentleys 1908 The Process of Government reposed unread on one of my office bookshelves. When I finally began reading it during the winter of 20092010, a slow process began of understanding its relevance to contemporary political struggles. I realized that Bentleys noncynical political realism offered a way to think about injustice as part of the same reality of political life that promulgates just laws and principles. There is no contradiction between formal equality in law and real life inequality in reality because law is verbal and reality is a matter of action. The task is therefore to figure out what to do when stated rules and principles are violated in practice. I feel this to be a very urgent task, although I could not do more in this book than gesture at its challenges in the changing political world of our time.

I began writing this book before I realized it, in a short piece published in the 2013 Fall APA Newsletter on Philosophy and the Black Experience, Racial Inequality and a Theory of Applicative Justice. The content of that interruption was valuable for its sobering acquaintance with contemporary injustice and the legal support of it, when I took up this book again, finished it, and then revised it.

The final revisions benefited from excellent criticism. I am grateful to the Philosophy Department at Georgia State University for their reactions to a colloquium paper I gave, How Police Racial Profiling and Homicide Are Now Legal but Unjust, in March 2015. That paper was an expansion of ideas I presented at a University of Oregon panel presentation for the Multicultural Center and Ethnic Studies event, Black Lives Matter, in January 2015. In those presentations, my criticism of ideal theory and description of the legal structure that supports contemporary police racial profiling and homicide with impunity, both drew from the main ideas in White Privilege and Black Rights and extended them to the concerns of the present book.

I have had truly wonderful critics of the penultimate manuscript, who are concerned about the same kinds of injustice that concern me! Janine Jones was a conscientious reader of parts of chapters 5 and 6, with a number of insightful criticisms, although I did not follow all of them. I am also grateful to the two anonymous external reviewers for Rowman and Littlefield. One insisted that I had completely misunderstood John Rawlss thought experiment of deliberation behind the veil of ignorance in his A Theory of Justice and the second wanted me to say more about work in legal pragmatism. Closer to home, Alan Reynolds, a recent University of Oregon Philosophy Department PhD graduate said the same thing about my reading of Rawls. And so did Cheyney Ryan, my ongoing colleague, and to some extent Colin Koopman, my present colleague in the University of Oregon Philosophy Department. I have not taken up legal pragmatism in the final version of the manuscript, because I realized that my concerns are with methodological pragmatism, instead. As for Rawls, I saw that I had indeed misunderstood him, but I believe that my better understanding has resulted in a stronger criticism of ideal theory. I also learned from Sarah Hamid, a University of Oregon graduate student in journalism and communications, who pointed the way toward research in contemporary digital culture, which I had much neglected. Jon La Rochelle, a University of Oregon PhD student in philosophy, motivated me to think about locally focused political activism in terms of the second half of the book. Of course, I have not done all of this criticism full justice! Not only would it take several more books to accomplish that, but I confess to the usual kinds of inertia and stubbornness, as well. Still, this version now going to press is much improved as a result of all that response and feedback. The remaining flaws are not only all mine, but no one can say I did not have a chance to do a better job of correcting them.

I could not have completed the book when I did without sabbatical leave for spring term 2015, for which I thank both the University of Oregon Department of Philosophy and College of Arts and Science. I am very grateful to Jon Sisk and his crew at Rowman and Littlefield, especially Natalie Mandziuk who as editor, saw the book through its contract and put this version into production and to Chris Utter who has been assisting Jon Sisk with final editorial processes. I am indebted to Crystal Clifton for copy editing, and thanks to Elaine McGarraugh for skilled, patient, and responsive production management.

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.