Naomi Zack, PhD, Columbia University, has been Professor of Philosophy at Lehman College, CUNY, since 2019. She earlier taught at SUNY, Albany and the University of Oregon. Her most recent book is The American Tragedy of COVID-19: Social and Political Crises of 2020 (March 2021). Also recent is Progressive Anonymity: From Identity Politics to Evidence-Based Government (December 2020). Additional books include Reviving the Social Compact: Inclusive Citizenship in an Age of Extreme Politics (2018). She edited the Oxford Handbook on Philosophy and Race (2017) and Philosophy of Race: An Introduction (2018). Earlier books include The Theory of Applicative Justice: An Empirical Pragmatic Approach to Correcting Racial Injustice (2016), White Privilege and Black Rights: The Injustice of US Police Racial Profiling and Homicide (April 2015), The Ethics and Mores of Race: Equality after the History of Philosophy (2011/2015), Ethics for Disaster (2009, 20102011), Inclusive Feminism: A Third Wave Theory of Womens Commonality (2005), Philosophy of Science and Race (2002), and Race and Mixed Race (1992).

Naomi Zack was awarded the Phi Beta Kappa-Romanell Professorship, 20192020, with three lectures on intersectionality to be given on the Lehman campus, which were delayed until March 2022 due to COVID-19 lockdowns in New York City. She gave the John Dewey Lecture at the Pacific Division Meeting of the American Philosophical Society in April 2021. Zack has been teaching a new course, Disaster and Corona, at Lehman College, in addition to courses in modern philosophy, ethics, democracy, and race and ethnicity and ethics and race.

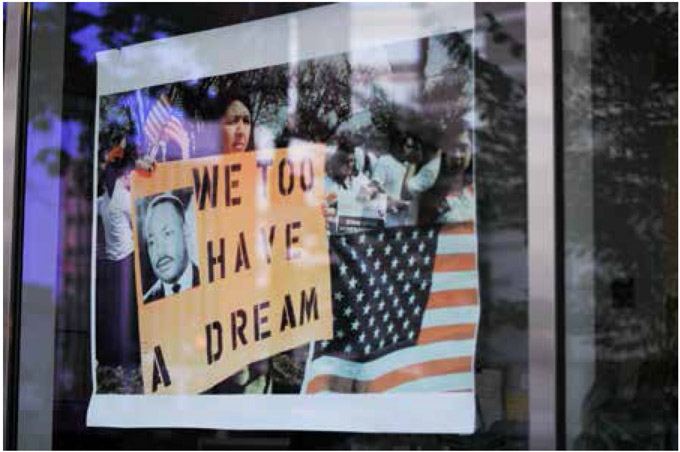

Washington, USA, July 8, 2011: The reflection of demonstrators on a window shop. Woman carrying a sign with the image of Dr. King and the slogan We Too Have a Dream in reference to women and Latinx rights. Getty Images: Montes-Bradley.

Martin Luther King Jr. (MLK) (19291968) has worldwide fame for his leadership in the US civil rights movement during the 1960s. His famous I Have a Dream speech was an ethical or moral call for just treatment of African Americans. King not only thought it was ethically right that justice be realized but that an important part of justice was race relations based on moral judgment. Thus, he said, I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. King wanted his children to be judged based on their morality. So, he was morally calling for moral judgment in race relations, a double moral request. In effect, he was telling his white audience not only that they should behave ethically to African Americans, but that part of this ethical behavior entailed that they should judge them in ethical termsthat is, judge the content of their character. To fully understand this, we need to understand the nature of ethics and morality, the nature of race, and how the two have been and continue to be related. We also need to understand the meaning of racial equality. After considering these subjects, we will return to Kings dream about white judgment based on the content of the character of African Americans, in light of the ideal of racial equality.

There is something distinctly human or at least special about ethics or morality. First, it is not merely a matter of intellectual judgment but is tied up with very strong feelings and emotions. Ethics is important, and most people take ethical issues very seriously. Still, ethical issues are not legal issuesmoral law is not government law. There can be ethically bad laws or there may not yet be ethically good laws that enforce morally right judgments and feelingsthat is, ethical reasoning may be ahead of or more progressive than legal reality.

Ethics or morality has two sidesright and wrong. Most people want to do the right thing and be morally or ethically good. With this comes praise of others who do the right thing and are morally good. The other side of praise for what is right or good is judgment and blame of those who do the wrong things and are morally or ethically bad. Of course, life is often complicated so doing the right thing may also involve doing the wrong thing, and doing the wrong thing may be unintentional or stem from good intentions. Nevertheless, right and wrong and good and bad are the fundamentals of ethical or moral thought and action.

Is there a difference between ethics and morality? Philosophers use the two terms interchangeably. But others may associate morality with personal behavior and ethics with workplace or professional action. The result is that a persons morality may be thought to pertain to behavior and opinions, whereas ethics is more formal and official. For example, choices in the consumption of nonfood substances and partners for intimacy may be a question of morality or morals, whereas behaving fairly to employees and subordinates involves ethics. In this book, we will stick with the idea of ethics, and what may be considered morals will simply be flagged as ethically neutral or neither good nor bad but a matter of taste. Related to matters of taste, but more important, are private personal choices, which may have moral importance for the person choosing, but should not be judged by others. And finally, some moral issues related to race are arguabletwo or more sides have equally plausible reasons for their positions so that moral conclusions cannot be determined.

Ethics is a general human thought process and standard for action for which philosophers have identified at least three specific systems: virtue ethics, deontology, and utilitarianism or consequentialism. But one major question arises before delving into these ethical systems: What is the source of ethics? The source of ethics has been religion, social norms or cultural traditions, and individual intuition. The ancient Greek philosopher Plato (428/427 or 424/423348/347 BC) in his dialogue Euthyphro introduced a dilemma for claims that ethics comes from the gods or God: Is something morally good or right only because it comes from God or does God approve of something based on another standard? If coming from God assures moral goodness or rightness, then what if different religions posit different Godly wishes? (And why should God be the ultimate ethical decider?) But if God decides what is good based on some other standard, then we do not need God but can refer directly to that other standard. Platos dilemma logically separated ethics or morality from religion, although based on intuition and cultural tradition, many people continue to connect ethics or morality to their religious beliefs.

At any rate, most agree that we should be good and do the right things. Differences arise in what specific traits and actions are considered good and right. Now is a good time to introduce the three main ethical systems identified by philosophers and from there we can answer the questions of what makes something a moral matter and who the subjects of morality are. Virtue ethics was introduced by Platos student Aristotle (384322 BC) in his Politics and Nicomachean Ethics. Aristotle believed that individual virtues could be developed by adults as part of living in a community. The virtues were neither inherited nor precluded by human nature but required two stages, first education in the virtues during childhood and second the practice of specific virtues. This practice required phronesis or practical wisdom: A person needs to identify the virtue called for in a given situation and act to the right degree based on their knowledge of that virtue. In time, such action would result in a settled trait of character and a