In 1975 Kit Bennetts was one of the youngest officers ever to serve in the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service. Fresh out of training, on routine surveillance duty one night he followed a big Mercedes from the Soviet Embassy, and witnessed a meeting between a KGB officer and an unknown man. That man turned out to be Dr William Sutch, one of New Zealands most eminent citizens. Five months later, after more surveillance and a major sting, Sutch was arrested and charged with passing information to the Russians.

A spectacular trial ensued New Zealands only espionage trial, ever at which Sutch was acquitted, only to die seven months later. Thirty years on, fascination with the case and speculation about whether Sutch was a KGB mole endures.

SPY is the first time an SIS officer has ever gone public. Written in a fast-paced, humorous style, and full of spycraft, it details how the SIS got their man, only to lose the case against him in court.

Wellington is the star of this book: a city of shadowy rendezvous points, dark alleys and winding streets through which the Russians raced in their big European cars, with the SIS in hot pursuit.

For Jacqu with love

and

dedicated to the memory of Eloise (19831997)

CONTENTS

The truth is great, and shall prevail, When none cares whether it prevail or not.

COVENTRY PATMORE (18231896)

Following the publication in October 2006 of Spy, my personal account of the operation that caught Dr William Sutch in a series of clandestine meetings with the KGB in 1974, I was invited to coffee with Dr Warren Tucker, then Director of the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service (SIS). In the months that passed since the release of the book, there had been a raft of publicity and reviews, including television coverage. Much as my old friend and colleague Paul Beaumont, then Assistant Director of the SIS, had predicted, Spy was well received by public and critics alike. The New Zealand Herald editorial of 4 October 2006 commented that, Bennetts unauthorised account has done the SIS a service. For the first time, someone had put a human face to the service and showed that the officers who worked there were simply ordinary New Zealanders doing a difficult and sometimes extraordinary job. The book shone a light, albeit a small one, on the workings of the SIS during a tiny but significant part of the Cold War. Spy was not a breach of security, rather an accurate record of a byline in New Zealands always fascinating history.

During the course of coffee, Dr Tucker took the opportunity to brief me on the content of The Mitrokhin Archive as it related to New Zealand, and with particular reference to what we all knew confirmation that Dr Sutch was a recruited asset of the KGB and had been so since before I was born. Dr Tucker requested that I keep the Mitrokhin information confidential, and that is what I did. I kept my counsel until the entire archive was made public by the British government in July 2014.

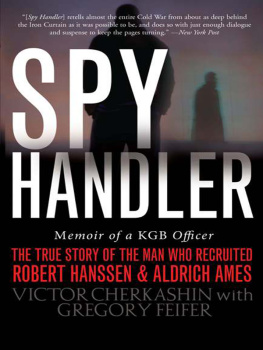

Vasili Mitrokhin was an officer of the First Chief Directorate of the KGB. He defected to the West and was exfiltrated from Russia to the UK, along with his family, in 1992, shortly after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The First Chief Directorate was responsible for almost all foreign intelligence gathering as part of the KGB.

Mitrokhin began his career as an operational officer but slowly, over time, had become disillusioned. He left his operational role and began working in the registry. While his disenchantment grew, he was careful to hide it. His role gave him almost unprecedented access to some of the most delicate KGB secrets, particularly as he was almost solely responsible for the transferring and archiving of the records of the First Chief Directorate when it moved from KGB headquarters, at The Lubyanka in Dzerzhinsky Square in the centre of Moscow, to Yasenevo on the southwestern edge of the city. The process began in 1972 and, each day, at considerable personal risk, Mitrokhin copied documents by hand and smuggled them out of the building. He began typing the handwritten pages and stored them at his family holiday home (dacha) some 36 kilometres south of Moscow. The sheer volume of data meant he was unable to maintain the level of typing required and so many of the notes remained handwritten until after his defection to the West. Over the years the archive developed to fill two aluminium cases and two tin trunks, which Mitrokhin buried under the floor of the dacha.

As the Soviet Union dissolved and self-destructed, Mitrokhin made his move and approached the Americans, who simply did not believe him. Mitrokhin turned to the Brits. The only thing they could not believe were their eyes when they saw the buried treasure and realised what they had. The trove proved to be the largest and most comprehensive archive of data ever to accompany a defector to the West.

There is an interesting New Zealand link to this part of the story. One of the MI6 officers charged with collecting and transporting the archive from the Mitrokhin dacha to the safety of the West was Richard Tomlinson. Tomlinson was born and raised in Hamilton, but moved to the UK as a young adult. After university he found himself in the world of intelligence and espionage, or the wilderness of mirrors. In 1997, after a dispute with his employers, the UK Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), Tomlinson was jailed when he attempted to publish a tell-all book. He subsequently wrote and published The Big Breach: From Top Secret to Maximum Security in 2001. He now lives in Europe.

Mitrokhin spent the remainder of his life in the UK sorting and typing out his handwritten notes, developing his archive, firstly with the intelligence services and then with Christopher Andrew, Professor of Modern and Contemporary History at the University of Cambridge. Professor Andrew is a formidable historian and academic his knowledge of the operations of the KGB in the West has no equal. He has written fifteen books, many focused on intelligence matters and, most recently, as the official historian of the Security Service (MI5), he wrote their official history, The Defence of the Realm: The Official History of MI5. He worked with Oleg Gordievsky, the most senior KGB officer ever to have defected to the West, and co-wrote with him KGB: The Inside Story. Mitrokhin and Andrew worked together for more than a decade to produce The Mitrokhin Archive: The KGB in Europe and the West, published in 1999, and the The Mitrokhin Archive II: The KGB and the World, which published in 2005, a little over a year after Vasili Mitrokhin died at the age of 81, in January 2004.

Shortly after the publication of volume one of the Mitrokhin papers in 1999, Professor Andrew told TVNZ that information relating to New Zealand and Australia would be included in the second volume, however, it did not appear and it has only now been made public.

In June 2014, the well-known and highly respected investigative reporter Phil Kitchin contacted me as he was considering a re-examination of the case forty years on. Without revealing the content of the archive, I suggested to Phil that he might want to explore the possibility of persuading the UK government to release that part of the Mitrokhin archive relating to Australia and New Zealand. In July 2014, quite without warning, the complete Mitrokhin collection was released to The Churchill Archives Centre ( www.chu.cam.ac.uk/archives ) at the University of Cambridge. Within a fortnight I was contacted by Dr Philip Dorling, an Australian journalist and historian whose particular specialty and expertise is in operations of the KGB and the GRU (Soviet Military Intelligence), especially in Australia. Dr Dorling had already located the Australian and New Zealand content and had had it translated. He was interested in my take on the content from the point of view of an old Cold War warrior. Within days Phil Kitchin had done the same and translated the pages relevant to New Zealand. Both men published their findings in newspapers on either side of the Tasman.