Maria Bargh (Te Arawa, Ngti Awa) is an associate professor in Mori Studies at Victoria University of Wellington. She researches and teaches in the areas of Mori politics and Mori resource management. She is co-lead of the governance and policy research team for the Biological Heritage National Science Challenge and recipient of the Royal Society 2020 Te Puwaitanga Research Excellence Award.

Julie L MacArthur is an associate professor and Canada Research Chair in Reimagining Capitalism at Royal Roads University. She specialises in environmental political economy, energy democracy, and participatory policy-making. Julie is the author of Empowering Electricity: Cooperatives, Sustainability, and Power Sector Reform in Canada (UBC Press, 2016), alongside a wide range of articles and chapters on community energy, sustainable community development, gendered employment in energy industries, environmental populism, and Green New Deal policies. She chairs the Women & Inclusivity in Sustainable Energy Research (WISER) network, and is a past chair of the New Zealand Environmental Politics and Policy Network.

To ng toa o te taiao and activists past, present, and future.

First published 2022

Auckland University Press

University of Auckland

Private Bag 92019

Auckland 1142

New Zealand

www.aucklanduniversitypress.co.nz

Maria Bargh & Julie L MacArthur and the contributors, 2022

ISBN 978 1 77671 092 8

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand

This book is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior permission of the publisher. The moral rights of the authors have been asserted.

Book design and layout by WordsAlive Ltd

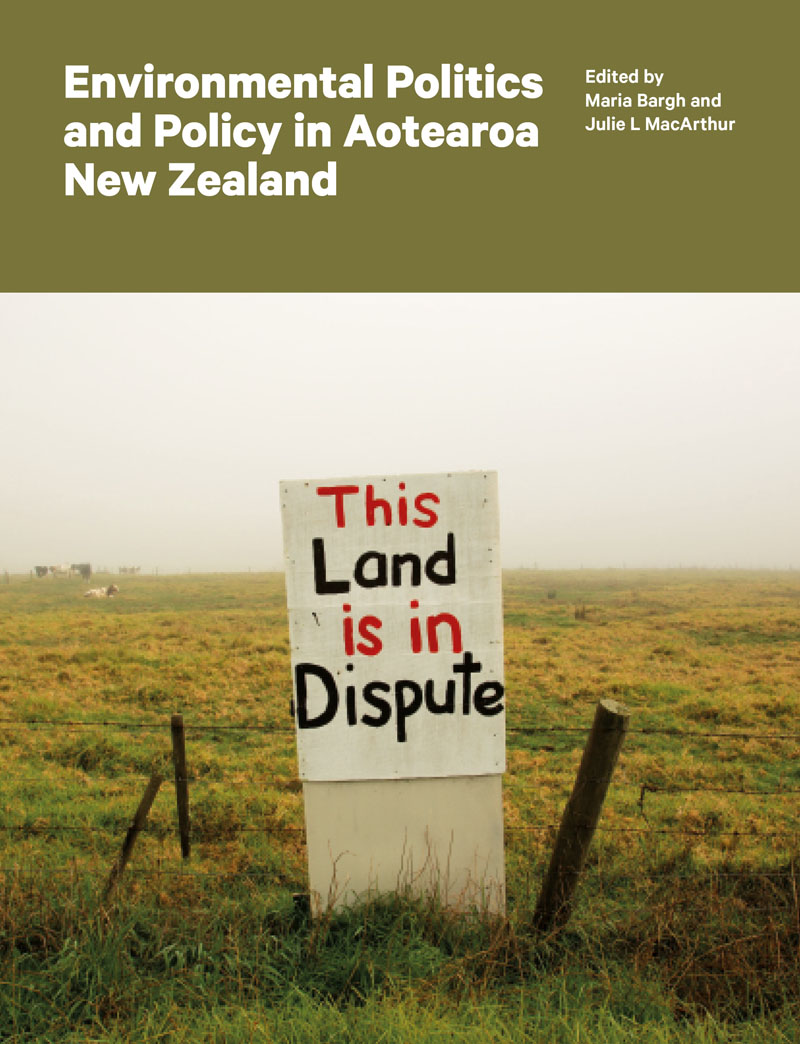

Cover design by Kalee Jackson

Cover photograph by John Darroch, Ihumtao, 2019

Contents

Acknowledgements

This volume emerged out of a series of meetings at the New Zealand Political Studies Association (NZPSA) annual conferences between 2015 and 2018. Thank you to the NZPSA for their continued support of the Environmental Politics and Policy Section, and to Ton Buhrs for his financial support of the Environmental Policy and Politics Network (EPPN) and environmental politics and policy research.

We would also like to extend our appreciation to Professor Janine Hayward, who was instrumental in shaping the volume and its contributions. It would not have existed without her wisdom and enthusiasm for the project.

Thank you also to those who helped turn a collection of chapters into a tangible final book. Sam Elworthy, Katharina Bauer, Lauren Donald, Teresa McIntyre and the team at Auckland University Press saw the value in this intellectual contribution early on and did an incredible job to bring a large and complex project to fruition in the midst of a global pandemic. Financial support for this project was provided by the University of Aucklands Performance-Based Research Fund (PBRF). Our thanks also to Claudia Gonnelli who provided research and manuscript assistance, doing an excellent job as we moved through the various drafts and phases of the project over the past three years.

Finally, no intellectual project exists in a vacuum. Our families have and continue to play an oversized role in supporting, motivating and inspiring our work to build ecologically sound and just futures. Ng mihi ki a koutou katoa.

1

Te Tranga Tuatahi Our Foundation

Julie L MacArthur and Maria Bargh

Introduction

The age of disconnection, when the environment, health, education, culture and the economy could all be seen as separable, is over. In 2020, a novel coronavirus (Covid-19) swept through every country in the world, infecting (as of 24 November 2021) more than 257 million people and leading to nearly 5.2 million deaths. In Aotearoa New Zealand, schools and businesses were closed as the government attempted to stop the spread of the disease and safeguard citizens. This experience has profoundly affected the way in which New Zealanders live their lives and will continue to do so for generations in the future. Globally, citizens endured a crash course on the concept of exponential growth, and how quickly crises can overwhelm existing infrastructure. The differential impact of the Covid-19 response on various segments of our population renters, owners and landlords, urban and rural dwellers, Pkeh and Mori, employed and unemployed, caregivers and single-person households exemplified how issues that spread without prejudice can hit some populations harder than others, raising important concerns around fairness and the ongoing impacts of colonialism. The Covid-19 virus, like its cousins SARS, MERS and swine flu, emerged in part due to the exploitation of natural resources allowing the virus to cross between species (OCallaghan, 2020). In many ways this event serves as a wake-up call: we can no longer pretend that we are separate from each other and from the natural world; we are inextricably intertwined.

Environmental researchers, activists and advocates have long pointed out our essential interconnectivity, most recently with respect to the urgency of the climate and broader environmental crises. Human activity is altering our 4.5-billion-year-old planet in profound ways, reaching biophysical planetary limits and ultimately undermining the basis for life as we know it; a process recognised in the concept of the Anthropocene (Dryzek & Pickering, 2019). The Earth is facing an era of mass species extinction, and recent scientific research has confirmed that the planet has already warmed 1.1C since pre-industrial times, with greenhouse gas emissions not set to peak until well past 2030. Policy actions will need to triple in intensity to meet 2C warming limits, and to quintuple to meet any 1.5C target (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC], 2018). Fierce debate continues today over the relationship between market economies and environmental degradation, and the appropriate role of the state in shaping (and reshaping) both of these. Globalisation the interdependent and widespread movement of capital, people, services and technology across borders also plays a key role in these debates as countries are linked together in the fast-moving ups and downs of financial markets, globe-spanning processing and commodity chains and resource-intensive transport. Longstanding debates also exist over whether we privilege human needs and desires (anthropocentrism), the natural world (ecocentrism), or some combination grounded in holism.

Scepticism about both the possibility and the desirability of large-scale social or environmental policy interventions has permeated policy-making in the past four decades. Neoliberalism, a political ideology focused on individualism, private property and a shift away from direct state intervention, has emphasised the preservation of economic growth and profitability over both kaitiakitanga (environmental guardianship) and manaakitanga (caring for each other) (Bargh, 2007). More recently, we have seen the rise of attempts to make environmental protection compatible with neoliberalism and capitalist market expansion through green growth policies that use green initiatives as a route to increased formal economic activity (Death, 2015). However, issues of distribution and justice are rarely front and centre in these policies. Indeed, between 1990 and 2015 the richest 1% of the worlds people were responsible for 15% of carbon emissions and 9% of the worlds total carbon budget, while the poorest half of the population accounted for less than half that (4%) (Gore, 2020).

Next page