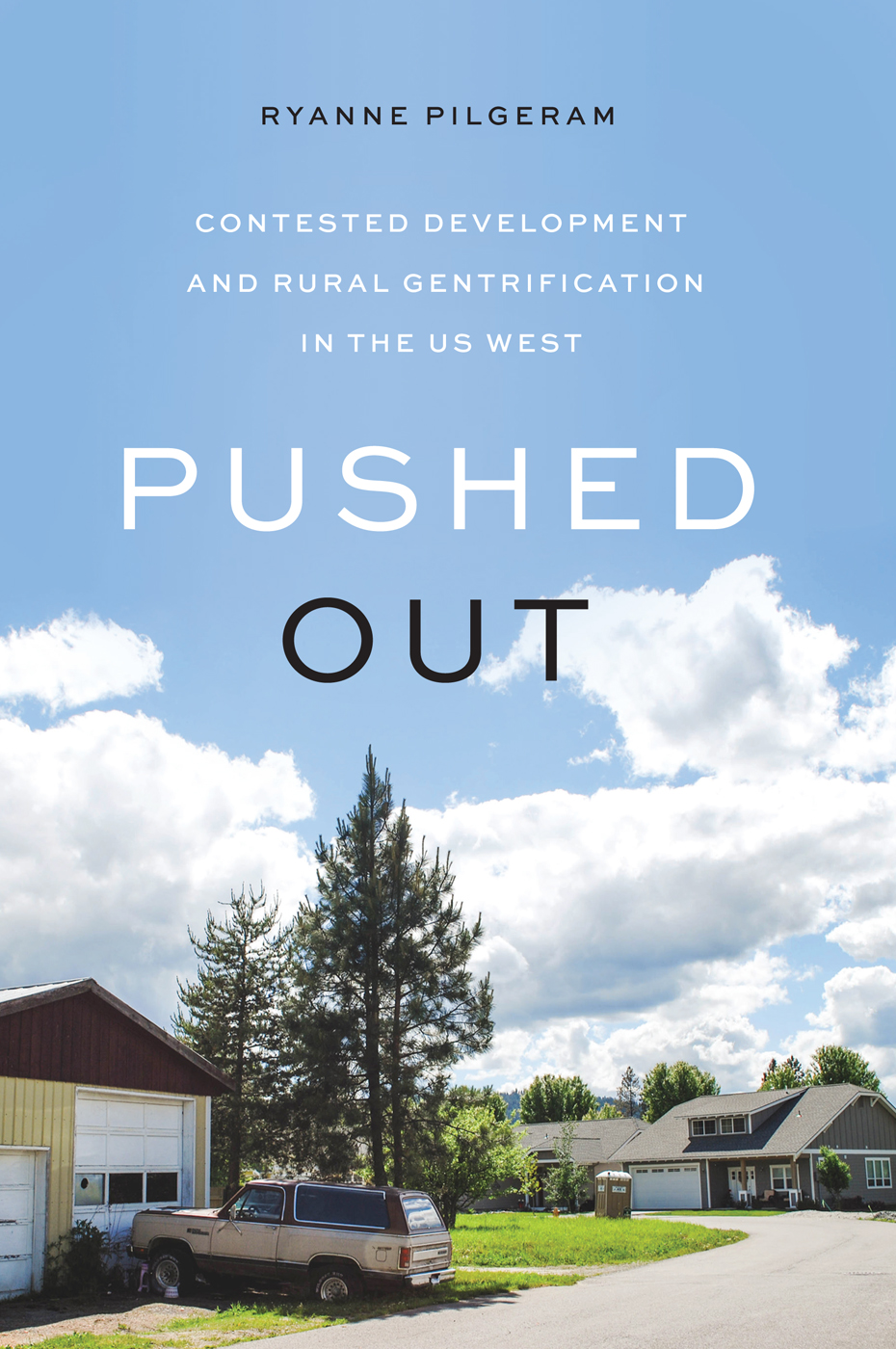

PUSHED OUT

PUSHED OUT

CONTESTED DEVELOPMENT AND RURAL GENTRIFICATION IN THE US WEST

RYANNE PILGERAM

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS | Seattle

Pushed Out was made possible in part by a grant from the Capell Family Endowed Book Fund, which supports the publication of books that deepen our understanding of social justice through historical, cultural, and environmental studies.

Copyright 2021 by the University of Washington Press

Design by Katrina Noble

Composed in Iowan Old Style, typeface designed by John Downer

Map by Chelsea M. Feeney, www.cmcfeeney.com

25 24 23 22 215 4 3 2 1

Printed and bound in the United States of America

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

uwapress.uw.edu

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Pilgeram, Ryanne, author.

Title: Pushed out : contested development and rural gentrification in the US West / Ryanne Pilgeram.

Description: Seattle : University of Washington Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2020047577 (print) | LCCN 2020047578 (ebook) | ISBN 9780295748689 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780295748696 (paperback) | ISBN 9780295748702 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: GentrificationIdahoDover. | Dover (Idaho)Economic conditions. | Dover (Idaho)Social conditions.

Classification: LCC HT177.D68 P55 2021 (print) | LCC HT177.D68 (ebook) | DDC 307.1/4120979696dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020047577

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020047578

The paper used in this publication is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI z39.481984.

To my mom

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Outside of North Idaho (where its never called Northern Idaho), most people have probably never heard of Dover. Sixty miles from the Canadian border and fifty miles from the nearest interstate, Dover is not a place you stumble upon. People who make the trek off the interstate and head north head to the picturesque beach town of Sandpoint, Idaho, three miles east of Dover, or Schweitzer Mountain, fifteen miles to the north, to ski. For decades, you might only have noticed Dover because the narrow highway severed the town into two parts: a sliver of town with the post office on one side, and most of the houses, the mill, the community center, and the church on the other. But even thats changed now. Today, a desperately needed new bridge and a widened highway mean you can speed over the community. If you keep your eyes on the road, you might never even realize youre passing over a town.

My interest in Dover started decades ago, when my mom, my sister, and I moved to a log house on a slough in a sort of no-mans-land between Sandpoint and Dover. I was starting my first year of high school, the daughter of a suddenly single mother. As a fifth-generation Montanan, I hated pretty much everything about Idaho. Theres a popular sentiment in Sandpoint that the first time you come across the Long Bridgethe two-mile bridge that crosses the lake and offers dazzling views of the mountainsyou never want to leave. But we had come in the back way, and it would be months before I crossed the Long Bridge, so I didnt find it difficult to hate Sandpoint. That said, it was hard to dislike Dover, though I tried.

I lived only a mile from Sandpoint High School, but I mostly took the bus to and from the school during my first year. After school, the bus made a wide, nine-mile loop, up Pine Street Hill and along gravel mountain roads, dropping off handfuls of students who lived in houses tucked into the woods. Thirty minutes later, we would finally pop out on Highway 2. We would make a quick trip up the highway, following the river west, then the bus would flip around in a gravel pit and finally head back east to make its two stops in Dover. Most of the students riding that route lived in Dover, but the Sandpoint High School bus routes put them at the bottom of the priority list. My sister and I were the last kids off the bus as it headed from Dover back toward Sandpoint, but the bumpy ride (always either too hot or too cold) was always better than walking.

Some of the people I met on the Dover bus have remained close friends. Dover, Idaho, is where I took those fragile first steps from adolescence into adulthood. For example, Dover is where I had my first (and only) car accident, a fender bender that happened at about five miles an hour. As is the custom in North Idaho, we left our bus riding behind when we got our daytime drivers licenses at age fourteen and a half. We all got crappy jobs and beater cars, and then proceeded to plow into each others mailboxes when we attempted to back out of long, icy driveways with very little experience (our parents looking on in horror from front windows).

Dover is also where I fell in love for the first time, with a boy whose recently divorced mom had moved out to a trailer that she covered in art she created from the driftwood and rocks outside her front door. It is where my mom, my sister, and I would picnic in the summer on a rare day that one of us was not working: a bucket of fried chicken on the sandy beach in the shade of the cottonwoods. And it is where I stood with a group of young women as we tried to support our friend who was mourning the death of her parents, taken much too young. We placed flowers in the cold water of the river that morning.

I left for college in 1999. Perhaps it was youthful inexperience, but the slow life of North Idaho, where mills closed, maybe even burned down, but the piles of sawdust didnt go away, made it difficult for me to imagine Dover as anything much more than a former mill town. I assumed it would become a bedroom community for Sandpoint, a place offering inexpensive house and a short drive to work.

I had just started working on my doctorate in sociology when I learned about the old mill development. Being two states away in the days before social media, the news came as a shock. Perhaps it should not have. The region frequently found its way onto best places to live lists, and the site was, in most ways, perfectly situated for development.

I earned my PhD in sociology in 2010 and was fortunate to land a position as an assistant professor at the University of Idaho. The research component of my job led me to study the lives of farmers in Idaho, but my interest in Dover remained. When I would go back to visit my mom, we would have dinner at the new restaurant that had been built there or just drive around to take in the changes. It was only after I earned tenure that I felt ready to turn my interest in the community into a professional undertaking. Because of my work on farming and agriculture, I had been asked to introduce a panel as part of a conference on the rural West. Listening to the scholars on that panel, particularly the brilliant Dr. Jennifer Sherman, I began to put the changes in Dover into a sociological and historical framework that I had not before. As I listened, the changes in Dover seemed nearly a perfect example of the phenomenon the researchers were discussing at that panel: rural gentrification.

It was these threads coming together that led me to write this book. I wanted to bring my experience as a researcher to a community that I very much cared about and delve deeply into the changes that had taken place. It is one thing to have the USDA classify your community in a particular way, but it doesnt tell you very much about the ins and outs of those changes. I was interested in the experiences of folks whod been in Dover for ninety years or more, as well as those who were new. I was also interested in understanding how the city had decided to rezone the land, since Dover seemed unique because of the relative power the city had over the land. Especially in places like Idaho, private property owners often have few restrictions on how they use their land. In Dover, however, the development was located within the city, and so the city council had the power to veto it. So why would some in the community seem to embrace the development?