Contents

Chapter 1

On-farm changes that have affected rural communities in the past 20 years

Chapter 2

Wairoa: Resilience and change

Chapter 3

Talking to communities: How other small towns view their resilience

Chapter 4

The Sustainable Land Use Initiative: A communitys response to an adverse event

Chapter 5

A new framework to measure resilience

Chapter 6

Creating an integrated perspective with modelling

Chapter 7

Pathways to future resilience: The TSARA programme

Chapter 8

The resilience of Mori land use

Chapter 9

Southland: An adapting landscape

Chapter 10

How will technology affect the fabric of rural communities?

Chapter 11

Entrepreneurship on New Zealand family farms

Chapter 12

Increasing indigenous biodiversity in farming landscapes

Chapter 13

An integrated approach to farming: Learning from mtauranga Mori

Conclusion

The future of rural resilience in New Zealand

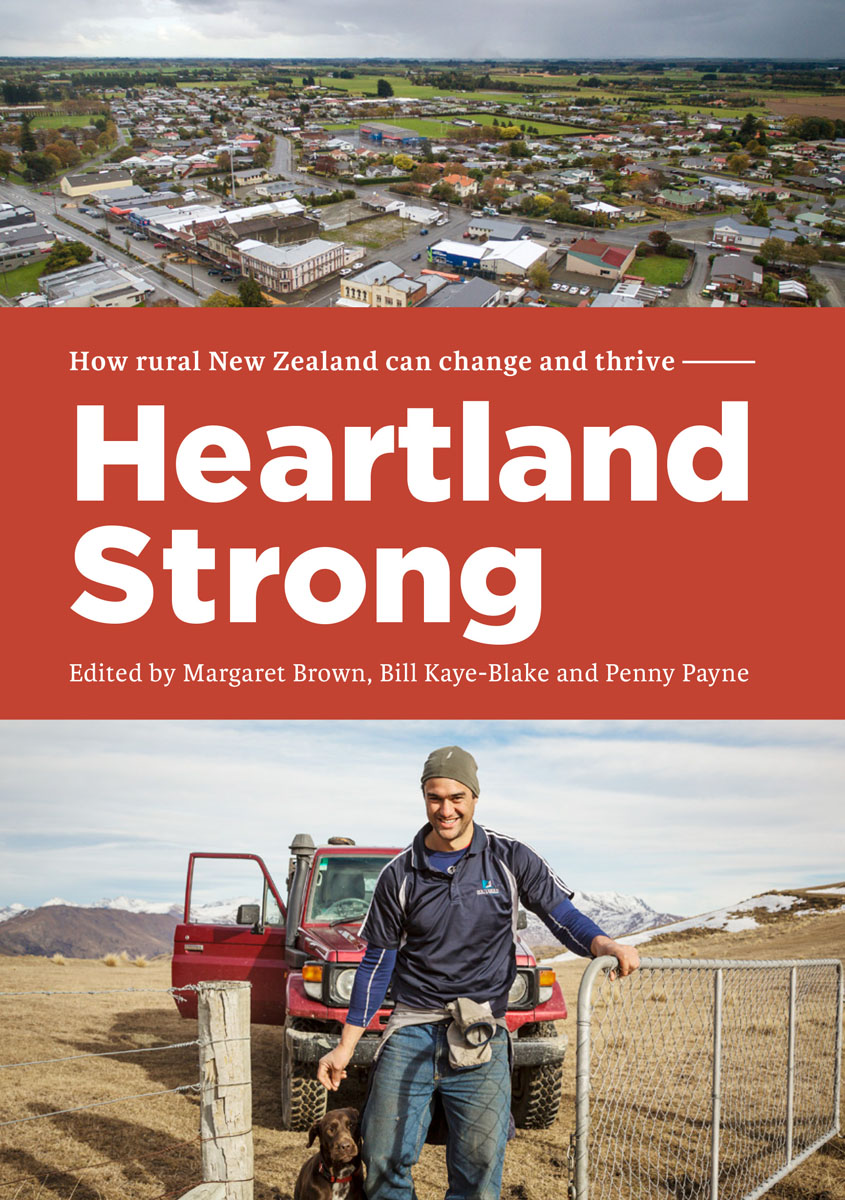

The Wairoa River, in northern Hawkes Bay. Beautiful landscapes and natural recreational assets, such as rivers, are seen by locals as some of the benefits of living in rural communities.

Rural towns are central to the resilience of New Zealands agricultural communities. The general store at Ongaonga has been trading since 1899.

Introduction

T he future of New Zealands rural communities is unclear. Empty shops, depopulation and lack of jobs are all offered as signs that many towns are dying. However, the strength of social ties and development of digital technologies, the innovations in rural entrepreneurship and the functioning informal economy suggest that some rural communities are in good health.

As researchers, we wanted to know what people in these towns thought about their own resilience, so we went and asked them. In 2016 we held a series of workshops in several small North Island towns and asked residents how their communities were doing. To some extent, what they said wasnt surprising. They pointed to businesses and government offices that had closed, to environmental issues that needed addressing, to schools and clubs that didnt have enough members, and to difficulties accessing services such as healthcare, post offices and banks.

At the same time, they talked about what they did have. They had good schools with excellent staff. They had natural resources such as rivers, lakes and bush for locals and tourists to use. They spoke of strong Mori culture with proud whakapapa and diverse iwi. Most of all, they talked about living in places where they knew people on the street and could stop for a natter and a cuppa. They identified strong rural communities and a sense of belonging.

Those discussions suggested an underlying resilience that isnt captured in some of the ongoing debates about the future of rural communities. They also echoed some of the research that the authors of this book have been undertaking for the past 10 years or more. Our research has investigated resilience on farms and in communities, as well as the links between the two. We thought it was time, therefore, to summarise what we have learned.

There are many definitions of resilience. In our research, we define it as the ability of a social system to adapt. This does not necessarily mean adapting to return to the way things were; it can also mean transformation and renewal within a community. In this way, we see disturbances to rural communities as sometimes negative, but also as opportunities for positive change.

While most resilience literature has focused on natural disasters or traumatic events, this book looks more at adaptation to gradual change, such as the depopulation of rural areas. This approach to resilience means we consider it to be a) ongoing, b) both positive and negative, and c) part of a wider system change.

We see this book as a part of a conversation with other writers and researchers who are interested in rural communities. We also think it fills gaps in the New Zealand literature on the resilience of rural communities. Some examples may help.

Economist Shamubeel Eaqub led New Zealanders to talk about zombie towns towns that wont die but are left to shuffle along as people and businesses leave. He raised provocative questions: should New Zealand have an active policy of putting dying towns out of their misery? How much responsibility does the rest of the country have for towns that no longer serve a clear function?

Massey Universitys Paul Spoonley undertook research on shifting demographics and the inevitable impacts on New Zealand regions.are mostly the result of past birth patterns and the passage of time. The expected result is fewer people in rural areas, with many of them being older.

These two examples show how the New Zealand literature tends not to explore the elements that make for vibrant or successful rural communities and tends to focus on one topic at a time: economics or demography or the environment. Our approach is to consider economics and demography and the environment, aiming for a holistic description of rural communities.

There is no getting away from the pressures, drivers and trends that are challenging the rural sector. The view popularised by Eaqub and Spoonley is that these trends will ultimately bring about the end of parts of rural New Zealand.

An alternative perspective

There is another view, however. Rural areas represent the bulk of the land mass of New Zealand, and therefore the bulk of its natural resources. These areas contribute significantly to the economy and have been growing in productivity. Rural communities contain quite a few of New Zealands people families and organisations who contribute to the social and cultural make-up of the country. Many of our rural communities represent what New Zealanders love about their country. They are friendly and tight-knit and provide a place to reconnect with the rural environment the rivers, the mountains, the small-town New Zealand feel. Rural areas also have a large proportion of tangata whenua, as well as their physical resources: marae, culture and trangawaewae (places to stand). Rural communities have shown themselves to be resilient over many years; that is likely to continue.

Based on many years of working with rural communities, we wanted to emphasise several aspects. Most importantly, people in rural communities, whether living in townships or not, do have options.

describes some of the differences, including the impacts of irrigation and intensification. There is also significant interest in new crops and new techniques.

Farmers have expanded into entrepreneurial businesses, as described in , including niche, value-add farming operations. Examples include organic farms, tourist-destination farms and farm-level diversification. Farmers are demonstrating adaptability in the face of a changing economic, social, environmental and cultural scene in New Zealand. In fact, the New Zealand Productivity Commission found that the primary sector, including agriculture, had the highest rate of labour productivity growth of any sector since 1985 and was above average between 2000 and 2011.

Next page