I know this to be true

Dedicated to the legacy

and memory of

Nelson Mandela

First published in the United States of America in 2020 by Chronicle Books LLC.

Produced and originated by

Blackwell and Ruth Limited

Suite 405, Ironbank,150 Karangahape Road

Auckland 1010, New Zealand

www.blackwellandruth.com

Publisher: Geoff Blackwell

Editor in Chief & Project Editor: Ruth Hobday

Design Director: Cameron Gibb

Designer & Production Coordinator: Olivia van Velthooven

Publishing Manager: Nikki Addison

Digital Publishing Manager: Elizabeth Blackwell

Images copyright 2020 Geoff Blackwell

Layout and design copyright 2020 Blackwell and Ruth Limited

Introduction by Nikki Addison

Acknowledgements for permission to reprint previously published and unpublished material can be found on . All other text copyright 2020 Blackwell and Ruth Limited.

Nelson Mandela, the Nelson Mandela Foundation and the Nelson Mandela Foundation logo are registered trademarks of the Nelson Mandela Foundation.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior consent of the publishers.

The views expressed in this book are not necessarily those of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

ISBN 978-1-7972-0273-0 (pb)

IBSN 978-1-7972-0337-9 (epub, mobi)

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, CA 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

Contents

Ultimately you judge the character of a society not by how they treat the rich and the powerful and the privileged, but by how they treat the poor. The condemned. The incarcerated. Because its in that nexus that we truly begin to understand truly profound things about who we are.

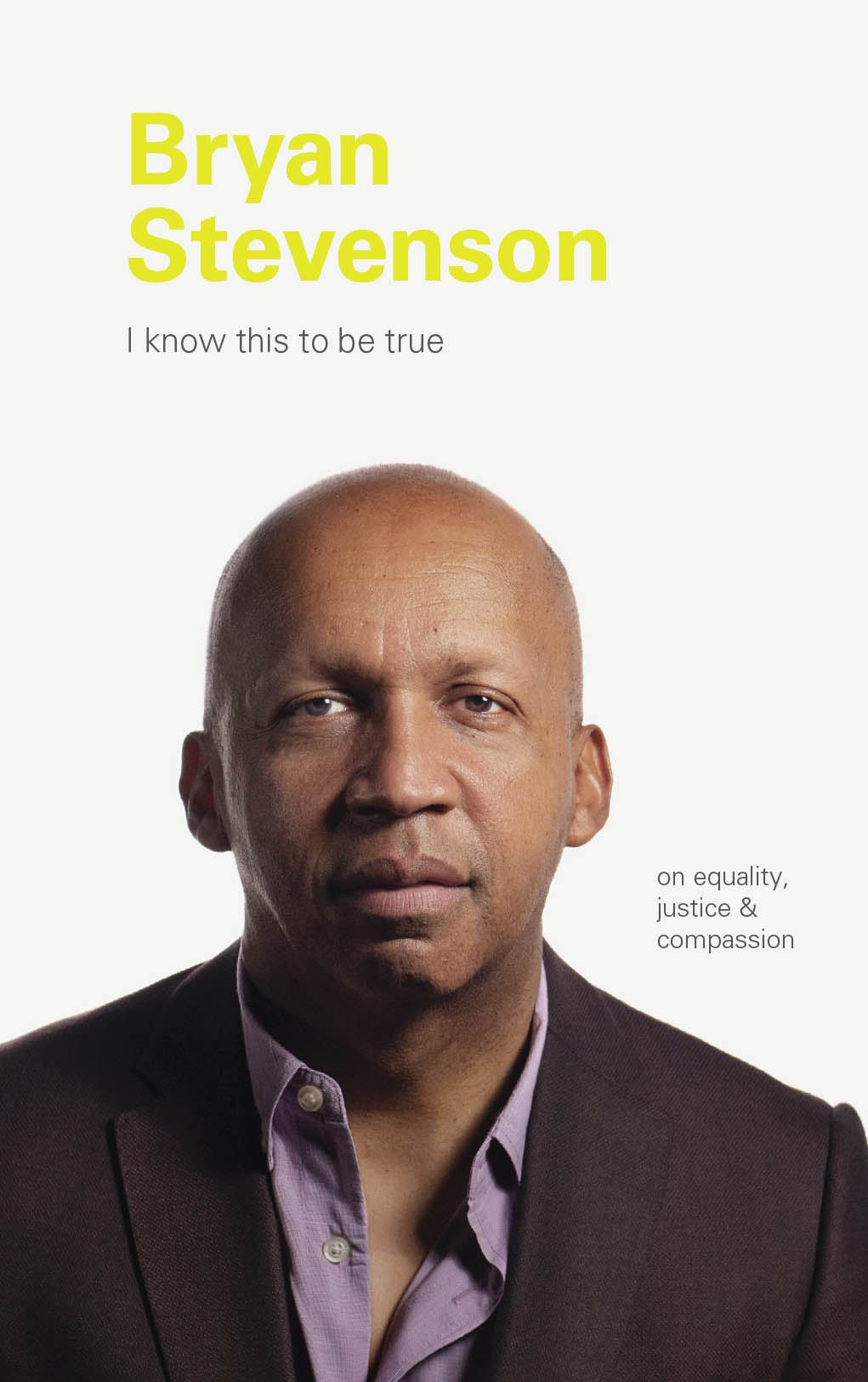

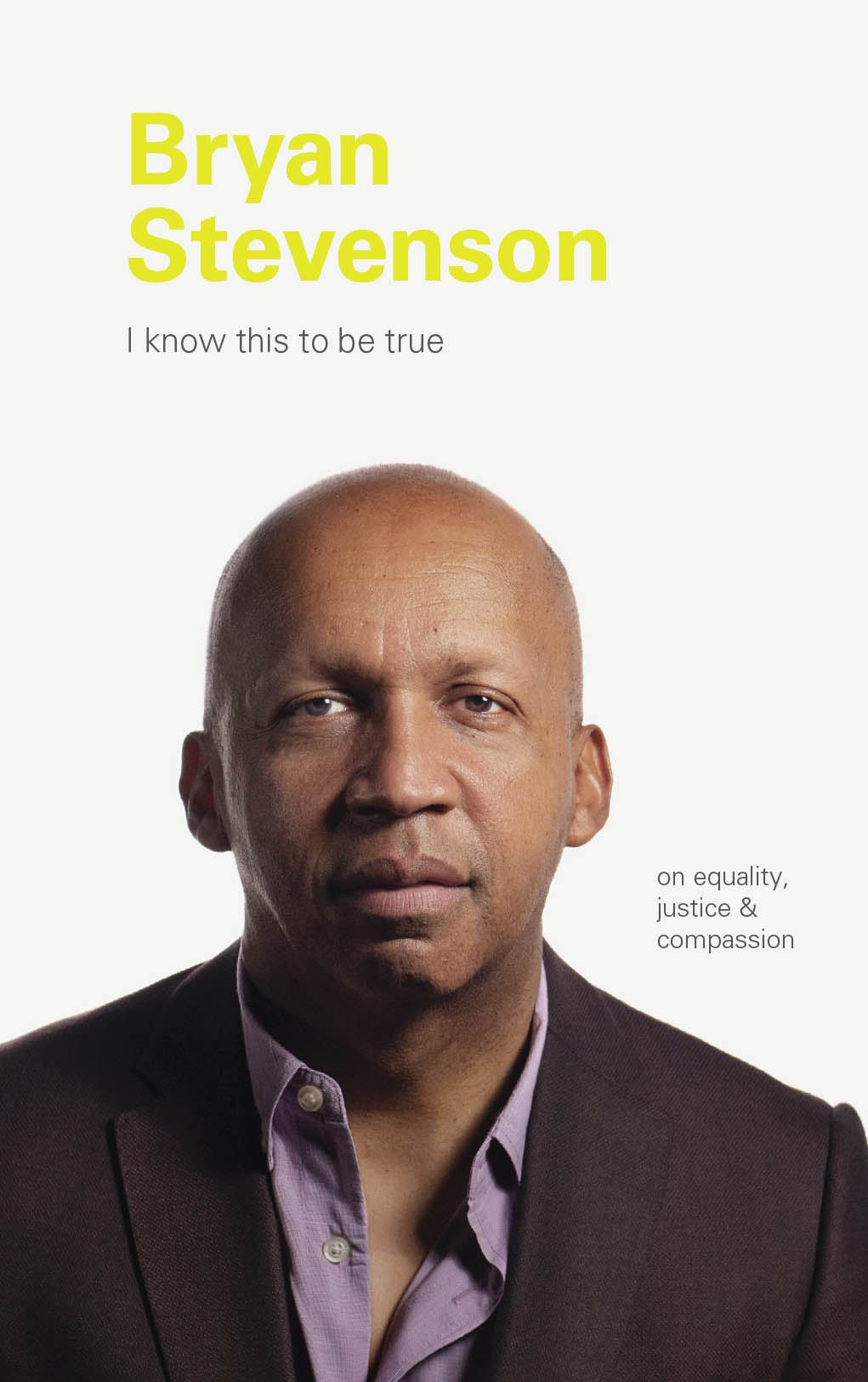

Introduction

In July 1989 Bryan Stevenson received a phone call from Holman Correctional Facility in Alabama, USA. The man at the end of the line was Herbert Richardson, an African American death row inmate whose execution was scheduled for one months time. He begged Stevenson to represent him. If there was no hope, he said, he didnt know how he could go on. Over the weeks that followed Stevenson made numerous attempts to stay the execution. The response was always the same: its too late.

Richardson was a Vietnam War veteran who suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. His mother had died when he was a small child and he had a history of drug and alcohol abuse. In a misguided bid to win his ex-girlfriend back, he had placed a homemade bomb on her porch in the hope that he would save her, and that they would rekindle their relationship. Instead, her young niece picked up the bomb and was killed instantly by the explosion. Despite his history of trauma and an obvious lack of intention to kill, Richardson was sentenced to death.

Stevenson stayed with him in the minutes before his execution. He was distressed, upset, and humiliated from having the hair shaved off his body. They prayed together and hugged, and, on 19 August 1989 at 12:14 a.m., Richardson died by electric chair. He was forty-three.

This case is just one of many that Bryan Stevenson has encountered throughout his long career as a public interest lawyer. But it had a profound impact it transformed the way he thought about the death penalty and it fuelled him in his fight to avoid execution for death row prisoners.

The death penalty isnt about whether people deserve to die... I think the threshold question is: Do we deserve to kill?

Stevenson grew up in the shadow of racial injustice. His great-grandparents had been born into slavery and he was raised in a racially segregated community in rural Delaware. As a law school graduate working for the Southern Prisoners Defense Committee in Atlanta, Georgia, USA, he encountered racial prejudice and oppression time and again not just in the cases he took, but at times in his personal treatment from white members of authority.

After co-founding the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) in 1989, the injustices he was confronted with grew at a rapid pace. Located in Montgomery, Alabama, USA, EJI is a nonprofit law centre that provides free legal aid to death row prisoners. As the organization expanded, its programme broadened to include excessive punishment, wrongful convictions, children sentenced to life in prison without possibility of parole, and mentally ill prisoners who were sentenced without their mental state being taken into consideration.

Stevenson has been guided by an unwavering belief that the worst things that happen to a person shouldnt define their life. Every person has the capacity to change and deserves the opportunity for redemption. Every person deserves to be treated equally. Yet for African Americans, this is not the case. Our society applies a presumption of dangerousness and guilt to young black men, and thats what leads to wrongful arrests and wrongful convictions and wrongful death sentences, not just wrongful shootings. Theres no question that we have a long history of seeing people through

Walter McMillian is an example of this historic discrimination. McMillian had been sentenced to death for the 1986 murder of Ronda Morrison, an eighteen-year-old white woman from Monroeville, Alabama. Despite having a solid alibi and multiple witnesses to confirm it, McMillian was targeted by local authorities who were under pressure to make an arrest. He had gained a reputation in the community for having an interracial affair with a married woman, earning the resentment of certain white locals.

With only the false testimonies of two career criminals and no physical evidence against him, McMillian was convicted of capital murder by a white-majority jury. The white judge, Robert E. Lee Key, used judicial override a practice legal in Alabama until 2017 to rescind the jurys recommendation of a life sentence and impose capital punishment.case, he received a phone call from Key, who tried to persuade him not to represent McMillian. Ignoring the judges advice, he persevered.

Faced with corruption and challenges at every turn and even multiple bomb threats Stevenson and his colleague, Michael OConnor, remained determined in their quest to free an innocent man condemned to die. After years of work, they succeeded, and McMillian was exonerated in 1993. His freedom was a compelling example of justice, and his resilience a vital reminder of the power of hope and forgiveness. Walter had taught me that mercy is just when it is rooted in hopefulness and freely given. Mercy is most empowering, liberating, and transformative when it is directed at the undeserving, Stevenson writes in his book, Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption. Walter genuinely forgave the people who unfairly accused him, the people who convicted him, and the people who judged him unworthy of mercy. And in the end, it was just mercy toward others that allowed him to recover a life worth celebrating.

Stevenson has made a career out of standing up for people like McMillian the oppressed, the marginalized and the voiceless. For over thirty years he has tirelessly fought for social justice and emphasized the ingrained nature of institutional racism in America. During this time he has won relief, reversals or release for more than 135 prisoners, and has helped achieve a US Supreme Court ruling that banned life in prison without parole sentences for children. But it isnt just his track record that should be acknowledged, nor his remarkable ability to highlight the urgent need to reform the American criminal justice system.

Next page