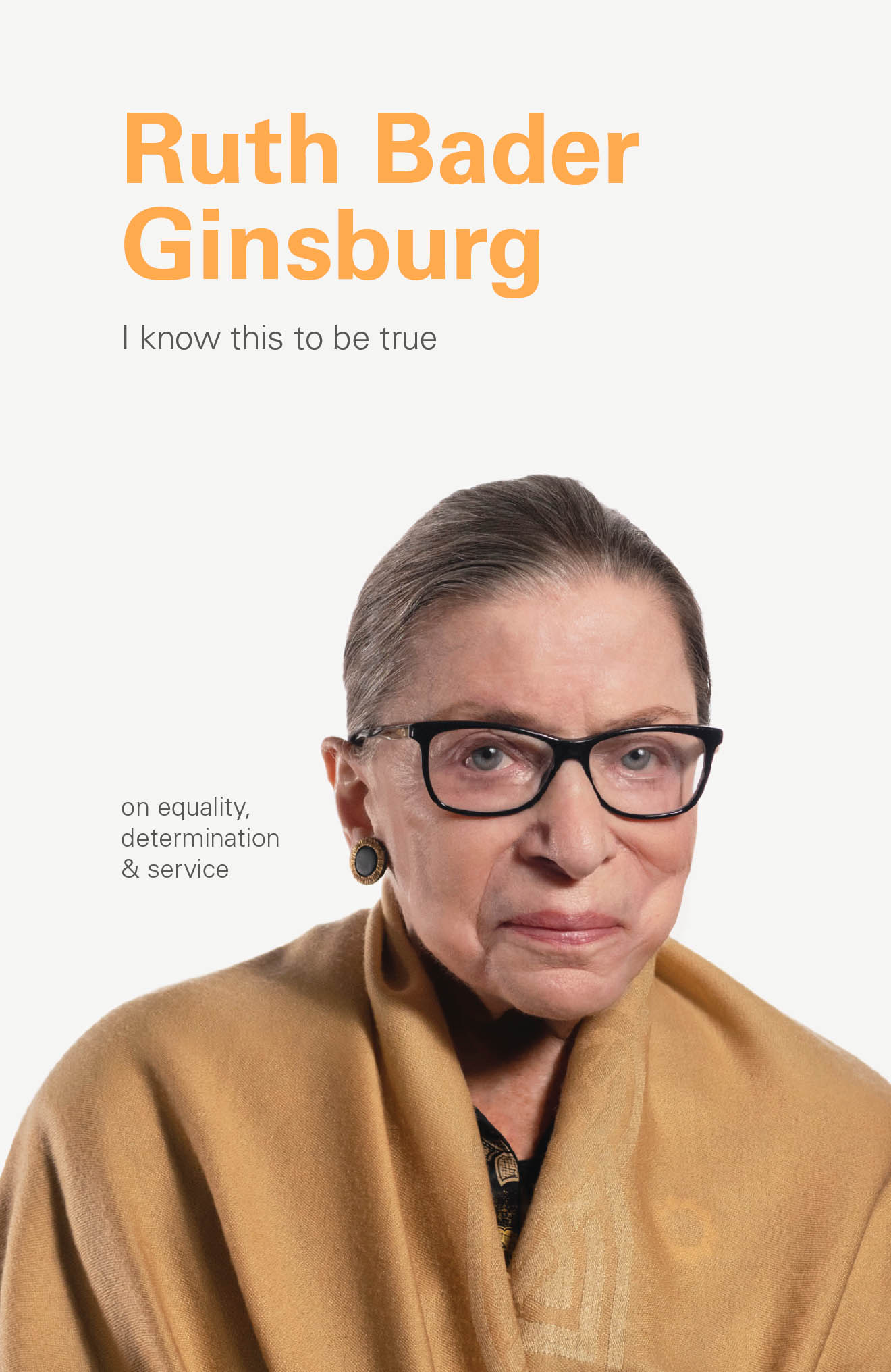

I know this to be true

Dedicated to the legacy

and memory of

Nelson Mandela

First published in the United States of America in 2020 by Chronicle Books LLC.

Produced and originated by

Blackwell and Ruth Limited

Suite 405, Ironbank, 150 Karangahape Road

Auckland 1010, New Zealand

www.blackwellandruth.com

Publisher: Geoff Blackwell

Editor in Chief & Project Editor: Ruth Hobday

Design Director: Cameron Gibb

Designer & Production Coordinator: Olivia van Velthooven

Publishing Manager: Nikki Addison

Digital Publishing Manager: Elizabeth Blackwell

Images copyright 2020 Geoff Blackwell

Layout and design copyright 2020 Blackwell and Ruth Limited

Introduction by Nikki Addison

Acknowledgements for permission to reprint previously published and unpublished material can be found on . All other text copyright 2020 Blackwell and Ruth Limited.

Nelson Mandela, the Nelson Mandela Foundation and the Nelson Mandela Foundation logo are registered trademarks of the Nelson Mandela Foundation.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior consent of the publishers.

The views expressed in this book are not necessarily those of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

ISBN 978-1-7972-0339-3 (epub, mobi)

ISBN 978-1-7972-0016-3 (hardcover)

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, CA 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

Contents

My dream for the world is that we will all be better off when women and men are truly partners in society at every level.

Introduction

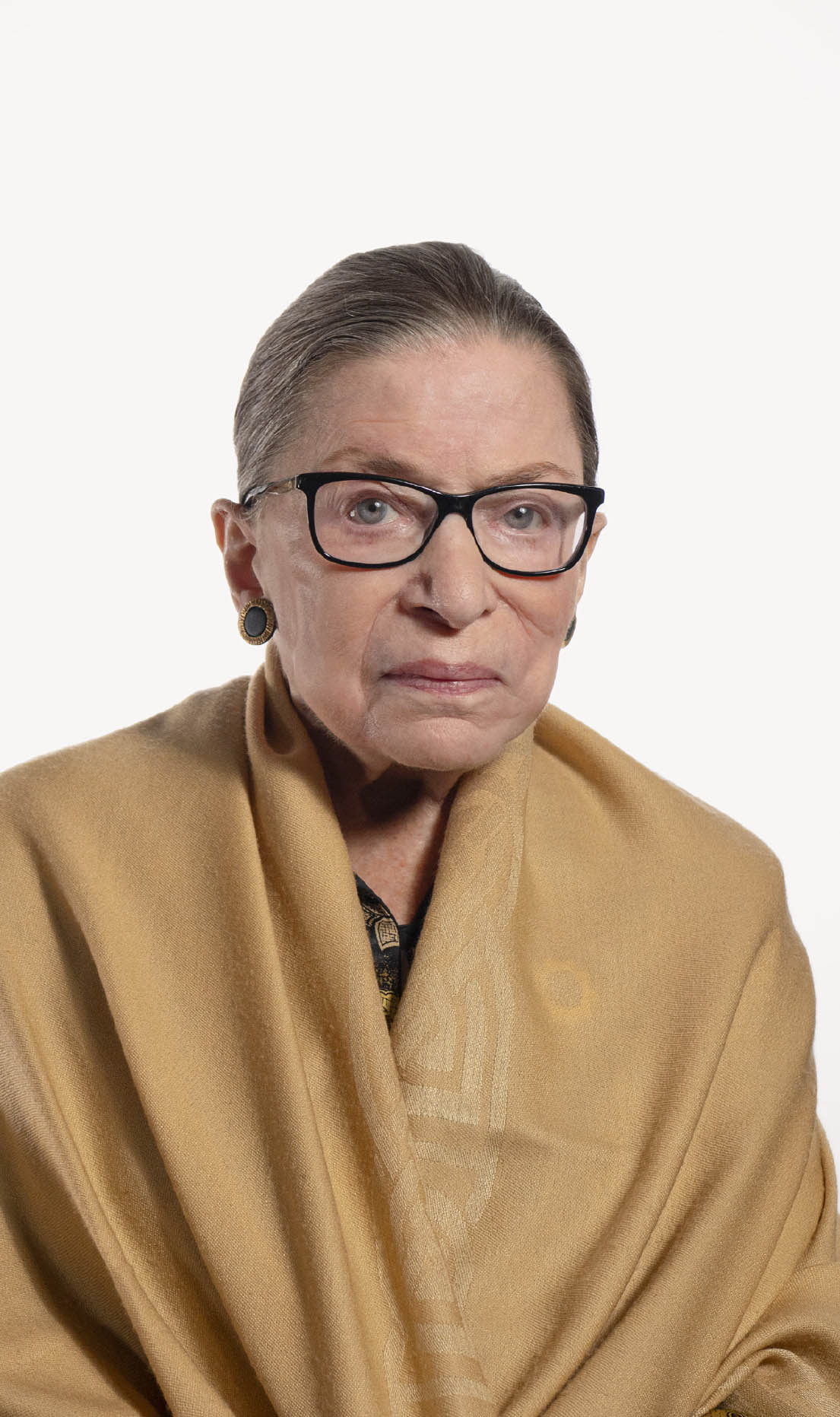

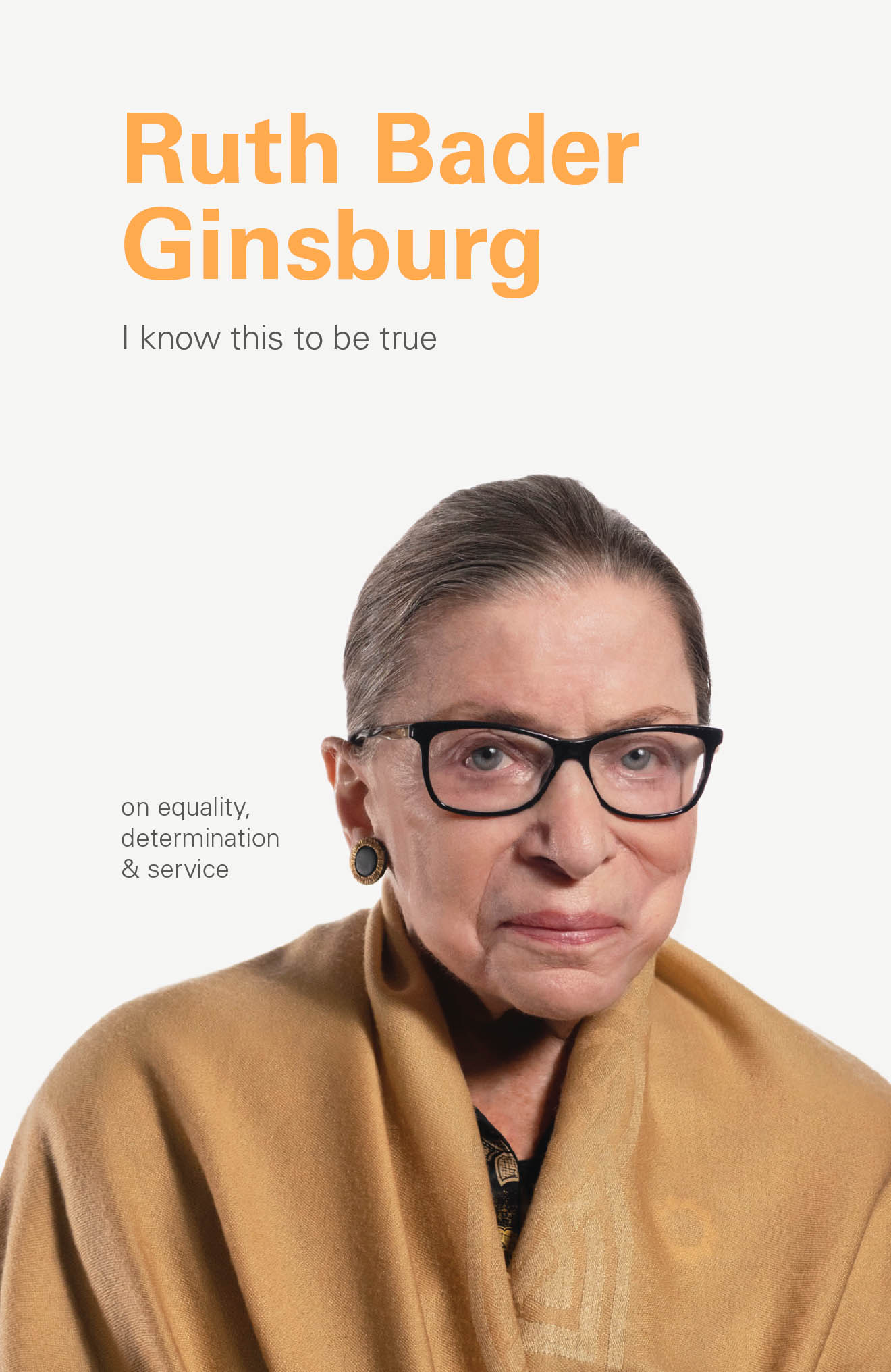

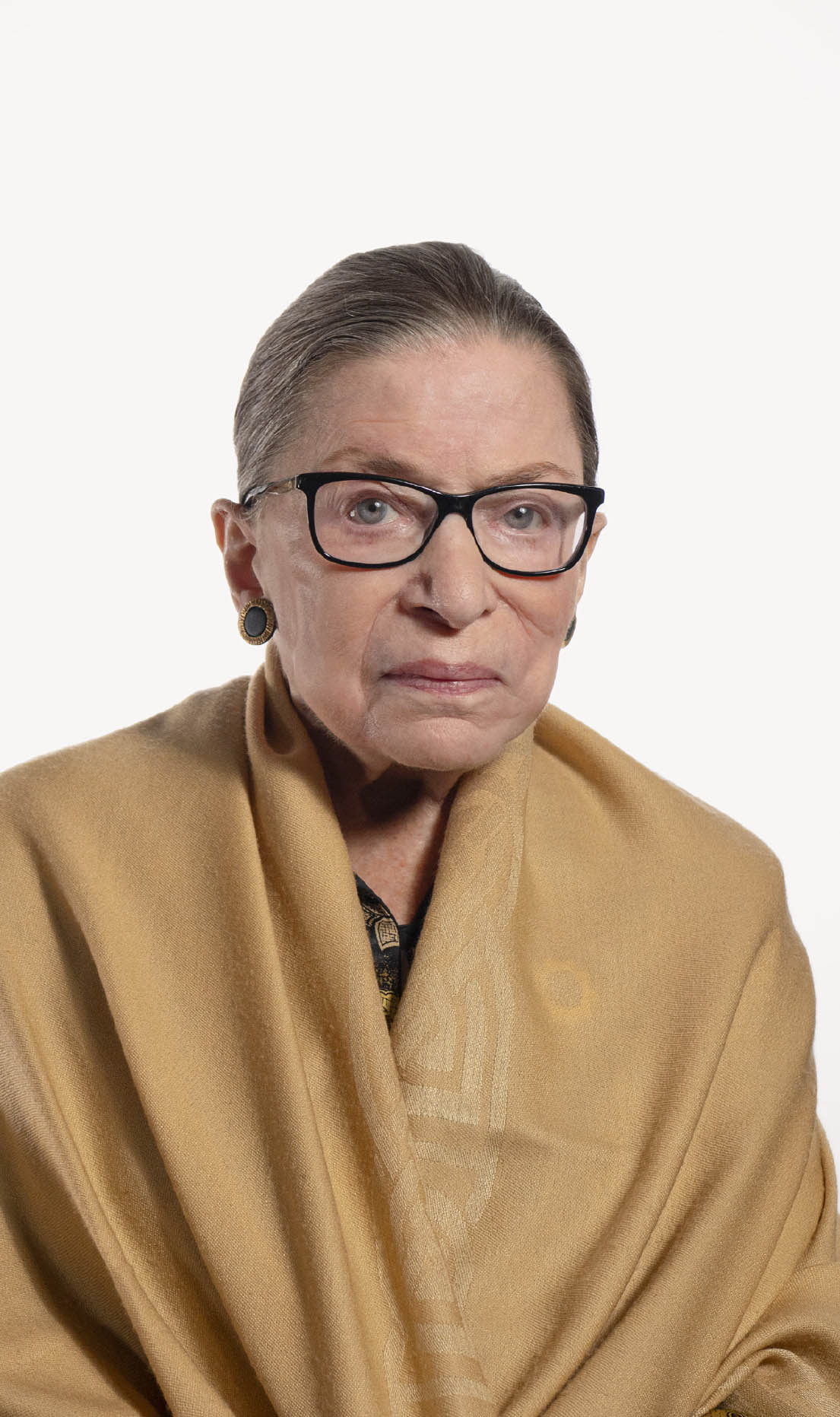

When Ruth Bader Ginsburg started Harvard Law School in 1956, she was one of nine women in a class of five hundred men. Only one of the teaching buildings had a womens bathroom. There was no legislation preventing discrimination in the US, and some law firms wouldnt even interview women for jobs. It was a different time. Things were tough. But Ginsburg wasnt swayed.

Fourteen months after her first child was born, she began her legal studies. She didnt need a career of her own her husband, Marty Ginsburg, was earning a law degree and could look forward to a well-paid job but she valued independence. A desire for autonomy stemmed from her mother, who passed away when Ruth was a teenager. In those ancient days, most parents of girls wanted them to find Prince Charming and live happily ever after. But my mother wanted me to fend for myself. Taking her mothers advice, she set about forging her own path in life.

During the Red Scare of the 1950s, This interest was developed even further in the early sixties, during time spent writing a book on Swedens judicial system. There, the idea that men were the breadwinners and women the housewives an idea prevalent in the US no longer held sway. Journalists for major publications wrote about gender equality as an ideal; an article in the Stockholm Daily questioned why, when both partners had full-time jobs, the woman was still expected to take care of the children, cook dinner and clean the house. In Sweden, Ginsburg came to see the law as a means to advance the equal citizenship stature of men and women.

A guiding belief in the ideal of equality has framed her life and work. Ending gender discrimination has remained a core focus; in 1970 she co-founded the first US law journal focused solely on womens rights, later co-authoring the first law school casebook about sex discrimination and the law. In 1971 she co-founded the American Civil Liberties Unions (ACLU) Womens Rights Project, which aimed to end gender-based discrimination in the nations laws. As director of the project she argued six cases before the Supreme Court over a five-year period and won five. When she became Columbia University Law Schools first tenured woman in 1972, she stood as proof of the possibilities wrought by the burgeoning womens movement.

Albeit slowly, things were changing. During Ginsburgs time at the ACLU, the office received a gradual flow of complaints from women, ranging from those who couldnt receive health insurance for their family when a man in the same position could, to a female tennis player who comfortably beat her male opponents but was not permitted to join the varsity team. People were lodging complaints they were either too timid to make before or were sure they would lose. But in the seventies they could become winners because there was a spirit in the land, a growing understanding that the way things had been was not right and should be changed.

The road to progress wasnt smooth. Throughout her many years of tireless work Ginsburg has faced bigotry time and again. As a twenty-one-year-old working at Oklahomas Social Security Administration she was demoted because she was pregnant when her employment commenced. (A decade later when she became pregnant again while working at Rutgers Law School, she wore her mother-in-laws clothing to hide the pregnancy.) On securing her first position as a professor in 1963, she was told by the Dean that, because her husband had a good job, she would earn less than her male colleagues. And in the early days of her career, she was refused positions as a law clerk because of her gender. When she asked one of the judges why, he told her working face to face with a woman would make him uncomfortable.

Yet rather than being disheartened by the setbacks she encountered, Ginsburg viewed them as opportunities to inform and enlighten. Some people just didnt understand why it was wrong to shield women from work as a lawyer, police officer, airplane pilot, and other fields of human endeavor. As an advocate in Minds could be informed, opinions changed, and progress achieved.

When she was appointed a judge of the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in 1980, and then an Associate Justice of the US Supreme Court in 1993, Ginsburg was able to continue her important work. With a career spanning nearly six decades, she has dedicated her life to achieving equality. And in an age where it is desperately needed, she remains a stalwart supporter of justice and a reminder of the power of hope. The progress has been enormous, and that is what makes me hopeful for the future. The signs are all around us.

It takes not only talent, but willingness to work hard, to make dreams come true.

Prologue

It was beyond my wildest imagination that I would one day become the Notorious RBG. I am now eighty-six, yet people of all ages want to take their picture with me. Amazing!

If I am notorious, it is because I had the good fortune to be alive and a lawyer in the late 1960s. Then, and continuing through the 1970s, for the first time in history, it became possible to urge before courts, successfully, that equal justice under law required all arms of government to regard women as persons equal in stature to men.

In my college years, 1950 to 1954, it was widely thought that women were not suited for many of lifes occupations lawyering and bartending, military service, foreign service, driving trucks, piloting planes, policing, serving on juries, to take just a few of many examples that now seem senseless.

Next page