Contents

Page List

Guide

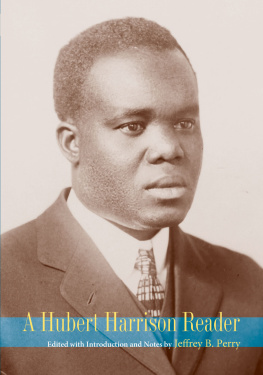

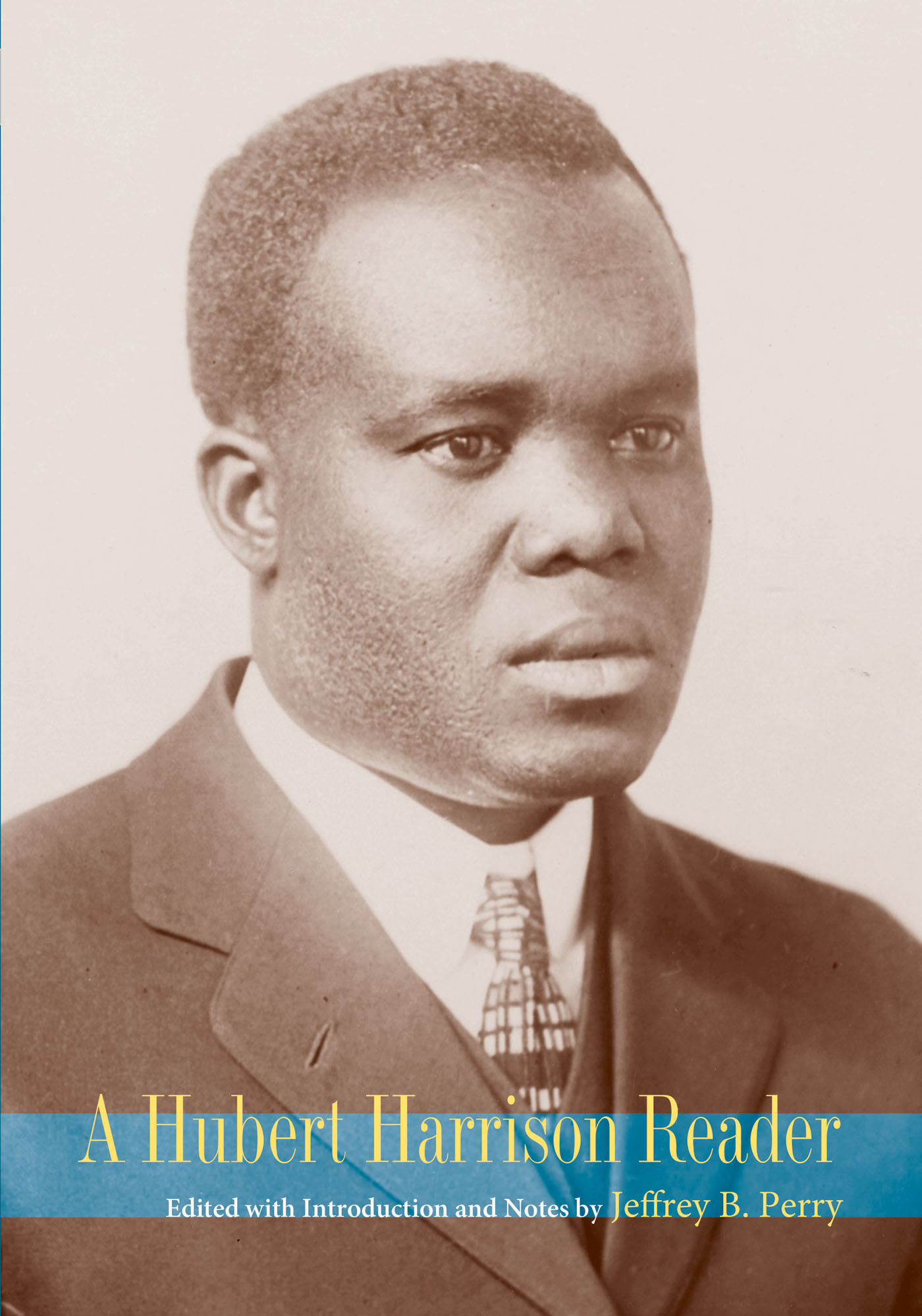

A Hubert Harrison Reader

A Hubert Harrison Reader

Edited with Introduction and Notes by

Jeffrey B. Perry

Wesleyan University Press | Middletown, Connecticut

Wesleyan University Press

Middletown, CT 06459

www.wesleyan.edu/wespress

2001 by the Estate of Hubert Henry Harrison

Introduction, commentary, and notes 2001 Jeffrey B. Perry

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Design and composition by Julie Allred, B. Williams & Associates

Paperback ISBN: 978-0-8195-6470-2

Ebook ISBN: 978-0-8195-8022-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Harrison, Hubert H.

A Hubert Harrison reader / edited with introductions and notes by Jeffrey B. Perry.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-8195-6469-9 (cloth)ISBN 0-8195-6470-2 (pbk.)

1. Afro-AmericansIntellectual life20th century. 2. Afro-AmericansPolitics and government20th century. 3. Afro-AmericansBook reviews. 4. Harrison, Hubert H.Political and social views. 5. Harlem Renaissance. 6. United StatesRace relations. 7. United StatesSocial conditions20th century. I. Perry, Jeffrey Babcock. II. Title.

E185.6.H28 2001

973'.0496073dc2100-051322

To Aida Harrison Richardson

To Aida Harrison Richardson

Becky Hom

Perri Lin Hom

Theodore William Allen

and the memory of

William Harrison

For the Cause that lacks assistance;

For the Cause that lacks assistance;

For the Wrongs that need resistance;

For the Future in the distance

And the good that we can do.

The Voice, front-page banner box; adapted

from the poem What I Live For by Mrs.

George Linnaeus [Isabella] Banks (18211897)

Contents

Acknowledgments

D uring the 1960s, I, like many others, was deeply affected by the civil rights movement and other struggles for social change in the United States. As a student I was afforded some opportunity to study, research, and interact with scholars. My ancestral roots, as far back as they are identifiable, are entirely among working people. These factors and many related experiences have led me to a life in which I have tried to mix worker-based organizing with historical research and writing. My major preoccupation has been the successes and failures of efforts at social change in the United States, and my major focuses have been on the role of white supremacy in undermining efforts at social change and the importance of struggle against white supremacy to social change.

These assorted influences and interests have provided me with a certain openness to the contributions of working class and antiwhite-supremacist intellectuals. It was in this context that I encountered the work of Hubert Harrison in the early 1980s. When I first read microfilm copies of Harrisons two published books I was arrested by the clarity of his writing and the perceptiveness of his analysis. I immediately sensed that I was encountering a writer of importance. I searched for what information I could find on him and was several hundred pages into a dissertation and projected biography when, through the help of two Virgin IslandersG. James Fleming, Professor Emeritus of Morgan State University in Baltimore, and June A. V. Linqvist (a relative of Harrison), librarian at the Enid M. Baa Library and Archives in Charlotte Amalie, St. ThomasI was put in contact with Harrisons daughter, Aida Harrison Richardson, and his son, William Harrison.

I met Aida and William for the first time in 1983. Aida was a former schoolteacher and principal, and William a former attorney; both were socially aware, race-conscious individuals who knew the value of their fathers work. They, along with their mother, the late Irene Louise Horton Harrison, had preserved the remains of Hubert Harrisons once-vast collection of papers and books in a series of Harlem apartments. After several meetings and discussions of their fathers work they very generously granted me access to their fathers materials. To Aida and William and to Aidas son, Charles Richardson, and Williams daughter, Ilva, who have similarly extended support and encouragement, I am forever grateful. Their generous spirit, human kindness, and willingness to support my efforts as biographer and chronicler of Hubert Harrisons life have left a lasting impression on me and inspired my work.

I was influenced toward serious study of matters of race and class in America by the work of an independent scholar and close personal friend, Theodore William Allen, whose insightful and seminal writings on the role of white supremacy in United States history and on race in America have attracted increased attention. Familiarity with Allens work disposed me to be receptive to the work of Harrison, another independent, antiwhite-supremacist, working class intellectual.

When I was a doctoral student at Columbia University in the 1980s, my principal advisors, Hollis R. Lynch and the late Nathan I. Huggins, offered the encouragement, support, and constructive critical comments that strengthened my research in its early stages and emphasized Harrisons importance. Their assistance included helping me to put together an exceptional team of dissertation readers, which included Professors Eric Foner, Charles V. Hamilton, and Elliot Skinner. These scholars read my manuscript critically and offered constructive suggestions and encouragement that pushed me to improve my work.

Subsequent drafts of writings on Harrison were read, commented on, and encouraged by Ernest Allen Jr., Theodore William Allen, Gene Bruskin, Robert Fitch, Bill Fletcher Jr., Henry Louis Gates Jr., Geoffrey Jacques, Portia James, and Jack ODell. Winston James, when called on, offered helpful discussion, and Manning Marable encouraged further work on Harrison by helping to publish a shortened form of the introduction to this work in Souls, the critical journal of Black studies that he edits.

Readers of either my dissertation or the Souls piece who offered comments and encouragement applied toward this work include Sean Ahearn, Norman Allen, Tomie Arai, Rosalyn Baxandall, Peter Bohmer, Alexis Buss, Kwame Copeland, James P. Danky, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Ralph Dumain, Steve Early, Dan Georgakas, Ted Glick, Don Hazen, Donna Katzin, Yuri Kochiyama, Kazu Iijima, Jane Latour, David Lawyer, Mike Merrill, Carole Mihalko, Jim Murray, Reverend Kay Osborn, Angelica Santamauro, David Slavin, Ann Sparanese, Michael Spiegel, Clarence Taylor, Andres Torres, Timothy B. Tyson, Joyce Turner, Michael Votichenko, Joel Washington, and Komozi Woodard. Important encouragement, feedback, and constructive criticism has also been offered by brothers and sisters in Local 300 of the National Postal Mail Handlers Union and by other trade union activists.

Throughout my research I have found librarians and library workers to be consistently helpful and generous with their time and expertise. (I note, however, that a great gap often exists between the value of the services they provide and the compensation in wages and benefits they receive.) I am particularly thankful to the staffs at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture (SCRBC), New York, New York; the New York Public Library (NYPL); the Columbia University libraries; the Tamiment Institute in the Elmer Holmes Bobst Library at New York University; the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University (MSRC); the Library of Congress (LOC); the National Archives (NA) in Washington, D.C., New York, New York, and formerly in Bayonne, New Jersey; the Florence Williams Public Library, Christiansted, St. Croix; the Frederiksted, St. Croix, Public Library; the Landarskivet, Archives of Sealand, Lolland-Falster and Bornholm, Copenhagen, Denmark; the Marx Memorial Library, London; the British Library, London; the Hoover Institution of War, Revolution, and Peace, Stanford University; the Municipal Archives and Records Center, New York, New York; the United States Postal Record Center, St. Louis, Missouri; the Brooklyn, New York, Public Library; the Paterson, New Jersey, Public Library; the Free Library of Philadelphia; the Westwood, New Jersey, Public Library; the Rutgers University libraries; the Firestone Library at Princeton University; the Lenin State Library, Moscow; the Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana; the Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, Minnesota; and the University of Minnesota libraries, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

To Aida Harrison Richardson

To Aida Harrison Richardson