THE COMEBACK

ALSO BY JOHN RALSTON SAUL

NON-FICTION

Voltaires Bastards

The Doubters Companion

The Unconscious Civilization

On Equilibrium

The Collapse of Globalism:

And the Reinvention of the World

Reflections of a Siamese Twin

A Fair Country: Telling Truths About Canada

Joseph Howe and the Battle for Freedom of Speech

Louis Hippolyte LaFontaine and Robert Baldwin

FICTION

The Birds of Prey

The Field Trilogy

I. Baraka or The Lives, Fortunes, and Sacred Honor of Anthony Smith

II. The Next Best Thing

III. The Paradise Eater

Dark Diversions

THE COMEBACK

JOHN RALSTON SAUL

For

Georges Erasmus

with admiration

CONTENTS

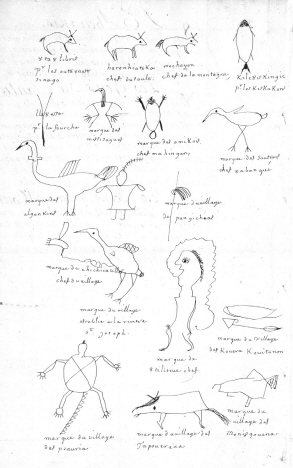

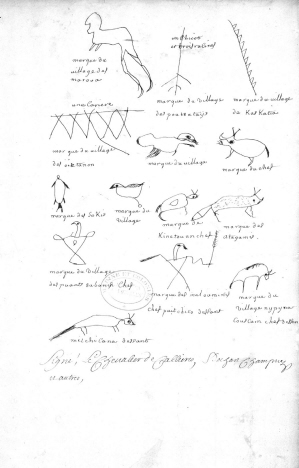

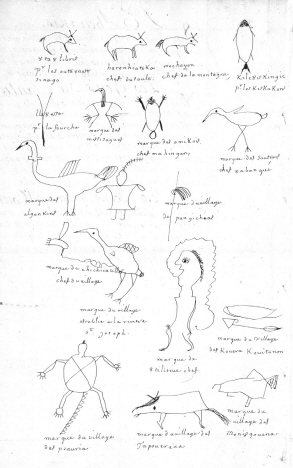

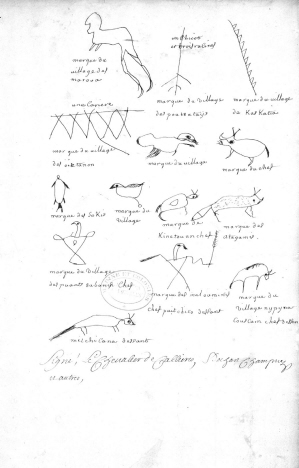

The Great Peace of Montreal, 1701. The signature page. This was a remarkable diplomatic agreement between oral and written cultures, but based on indigenous concepts. The Iroquois, forty other First Nations and New France all signed. Thirteen hundred delegates attended. This is the beginning of the Canadian idea of treaty. Library and Archives Canada, 3192491.

I

HISTORY IS UPON US

W e know we live in history. We know we can shape it, although far less than we would like. And when we do intervene, it is inseparable from the great force with which history moves, surging across generations with ease. The full impact of that intervention of getting it right or getting it wrong is something that will slowly unfold over decades, even centuries. So history both constrains us and demands of us a great deal. Most of the time we cant see its shape and instead feel ourselves caught up in mysterious tides, unable to make out the great flow. Or perhaps we dont want to.

But we are always somewhere in history. Struggling in the waves. Being dashed on the rocks. Or just paddling innocently along.

The winter of 201213 needs to be thought of in these terms. Idle No More swept into our lives. Indigenous people massed in protest where protest was not expected, in shopping malls, at intersections across the country, as well as on Parliament Hill. New young leaders could be read and heard in all the media. The established leadership, non-Aboriginal and Aboriginal, the media, the experts tried without success to shape or control this organic expression of frustration and anger. Federal political leaders attended with solicitude at the side of Chief Theresa Spence, who was on a hunger strike on Victoria Island. Had she died from the effects of her liquid fast, within sight of the Parliament Buildings, a dangerous line would have been crossed. Irreparable damage would have been done to Canadas social fabric, her death a modern version of Riels hanging. Events might then have slipped out of all control. Violence? We cannot know. In the end we stumbled out of the crisis. The governor general received the chiefs in a troubled atmosphere. There was a prime ministerial meeting to which some key chiefs refused to go unless the governor general was present.

The whole country seemed to be hypnotized by the seemingly abrupt arrival of indigenous people at the very centre of national consciousness. I say seemingly because the Canadian people and our government have not been paying attention. This was not just a rough patch in Aboriginal relations with the rest of Canada. It was not about personalities or a particular problem. It was not about Idle No More versus the Assembly of First Nations. Or various chiefs versus the national chief. Or those on hunger strikes versus those trying to negotiate. Each of those elements was part of a broad movement wrapped up in the forces of history. Then and now, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, each of us must try to fit the pieces together. Aboriginal people were at the very centre of national affairs because that is where they belong. They were at the centre of the national consciousness, as they should be, but in a way that reminded anyone willing to listen of what was and is at stake. This is the great issue of our time, the great unresolved Canadian question upon which history will judge us all.

Historic moments are always uncomfortable. They are always filled with strategic contradictions. Tactical contradictions. There are always divisions among those seeking more power for their cause. That is an almost necessary characteristic of movements seeking important social change. As for those in authority, they find themselves pulled and pushed in an atmosphere of crisis that melts the mechanical norms of power.

And so to those under attack in this case the Canadian government and some of the non-Aboriginal leadership elements of Canadian society it may seem that these divisions offer a cynical opportunity. To play one group of Aboriginals off against another. To attempt, for example, to discredit the Aboriginal leadership by attacking a handful of chiefs who overspend. Or a bit of corruption here. Or ineffectiveness there. Anything to avoid addressing real, long-standing questions. Or to avoid resolving real problems. But these are false opportunities. A false reading of what is happening.

Clever tactics or stalling wont make the situation go away and will resolve nothing. Most important, without a serious level of resolution, the fundamental flaws in this relationship will simply become more troubling for all of us and increasingly problematic for the existence of Canada.

This historic reality is not helped by the natural tendency of the media and of political backrooms to view their own reality through the details of the day. It is natural. And it is necessary. They are endlessly drilling down as they see it into personalities, rivalries, divisions, failures. This is how they perceive their job examining the entrails of chickens in order to tell us whether Caesar ought to go to the Forum.

This can also become a problem when dealing with a crisis, particularly a long-standing crisis. We are all caught up in the established narrative of the day. And within that narrative each of us is focused on our own particular realities. Our own habits, practical and emotional. This is normal. And in normal times it may work. But the key to dealing with a real crisis, one that goes beyond our personal realities, lies in our ability to move outside what we think of as normal. If the crisis is big enough, we have to reconsider the narrative or we can be destroyed by it. For example, the current prime minister, Mr. Harper, is usually locked fast onto an economic narrative of whatever is going on. A very particular economic interpretation at that. Such is his reality. As for Canadians at large, we have myriad realities. Some of them are as simple as getting to work on time or having access to gas for our cars. Anything that gets in the way annoys us. We have thousands of ambitions and concerns involving our families, our employment, our lives.

On broader social issues, we tend to focus on any sign of suffering. We are troubled by suffering, by the suffering of others. That is a classic Judeo-Christian lets say Abrahamic expression of empathy. Not a bad thing. It is a good emotive entry level into public dramas. But if non-Aboriginals define their relationship to the Aboriginal reality through their emotions, well then, this emotional drama may simply take the place of ensuring that the issues are dealt with. That kind of sympathy may simply reinforce the old narrative in which Indians are a problem and unsuited to survival in modern society because they have been so shamed by us as to have lost the self-confidence necessary to function in the real world. Lee Maracle, in a conversation with CBC Radio host Michael Enright on May 18, 2014, offered a sharp correction to this destructive sympathy. Shame is what other people call it. No one says it about themselves. In this case, if there is shame it should be felt by the perpetrators. Maracle: For any reconciliation to take place, the party that hurt you has to take part.

Next page