Contents

The Cambodian Wars

MODERN WAR STUDIES

Theodore A. Wilson

General Editor

Raymond A. Callahan

J. Garry Clifford

Jacob W. Kipp

Allan R. Millett

Carol Reardon

Dennis Showalter

David R. Stone

Series Editors

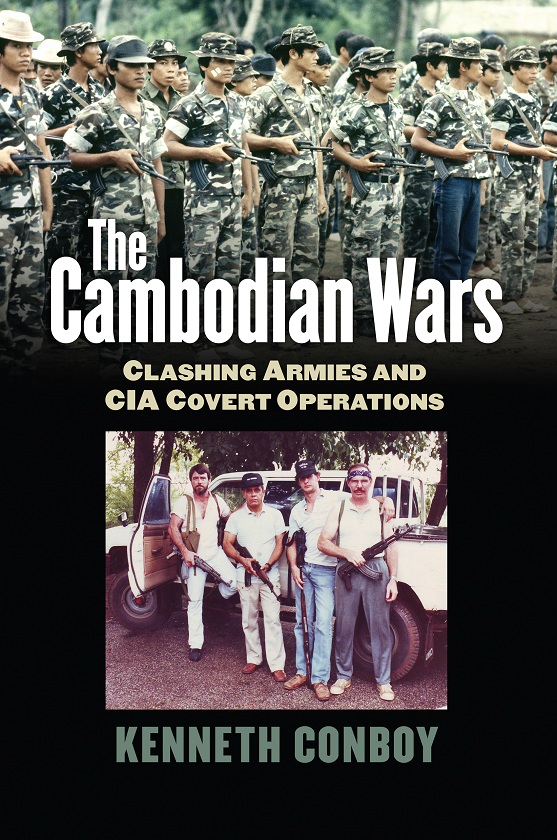

The Cambodian Wars

Clashing Armies and CIA Covert Operations

Kenneth Conboy

UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KANSAS

UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KANSAS

2013 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Conboy, Kenneth J.

The Cambodian wars : clashing armies and CIA covert operations/ Kenneth Conboy.

pages cm. (Modern war studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7006-1900-9 (cloth : alkaline paper)

ISBN 978-0-7006-2822-3 (ebook)

1. CambodiaHistory, Military20th century. 2. ArmiesCambodiaHistory20th century. 3. Political violenceCambodiaHistory20th century. 4. Espionage, AmericanCambodiaHistory20th century. 5. Paramilitary forcesCambodiaHistory20th century. 6. United States. Central Intelligence AgencyHistory20th century. 7. United StatesForeign relationsCambodia. 8. CambodiaForeign relationsUnited States. 9. United StatesMilitary relationsCambodia. 10. CambodiaMilitary relationsUnited States. I. Title.

DS554.8.C65 2013

327.1273059609045DC23

2013000730

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in the print publication is recycled and contains 30 percent postconsumer waste. It is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials z39.48-1992.

Contents

Illustrations

Maps

Photographs

Preface and Acknowledgments

This book has been nearly three decades in the making. To be fair, my focus during the initial decade was toward the war in Laos, where I was documenting a massive and extended paramilitary campaign conducted by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Over the course of interviewing dozens of CIA officers who had served in Laos, I encountered many who had spent shorter stints in neigh boring Cambodia. I dutifully jotted down their Cambodian anecdotes and filed them away.

Years later when researching a book on covert operations in North Vietnam, I once more came across CIA officers who had done Cambodian tours. Then when I wrote a book on the CIA operation in Tibet, again I interviewed officers who had Cambodian experience. Collectively, their tales were gaining critical mass.

It is perhaps fitting that I came to writing this book while researching others. After all, it has become clich to call the conflict in Cambodia a sideshow. During the Second Indochina Conflict, this was not an unfair characterization. Although Cambodia sometimes carried the headlines, the battles there were usually secondary to, or in support of, the main struggle in neighboring Vietnam.

This did not remain the case. By the time of the Vietnamese invasion of Democratic Kampuchea in 1978, and the subsequent war through 1991, Cambodia moved from sideshow to center stage. It was the main issue that defined the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) for more than a decade. It also came to symbolize the faultline between the socialist camps, with China and the Khmer Rouge on one side and the Soviets, with their Vietnamese proxies, on the other.

Throughout this period of events, and for different reasons, the United States had difficulty responding to the troubles in Cambodia. During the 1960s, limits largely followed from Cambodias nonaligned foreign policy. During the first half of the 1970s, a larger American role was proscribed by congressional restraints. Then during the 1980s, lingering effects of the Vietnam Syndrome led even the most hawkish members of President Ronald Reagans administration to downplay direct involvement in Cambodian affairs.

Enter the CIA. During those times when the Pentagon and Foggy Bottom were constrained with regard to what they could do in Cambodia, CIA covert operations were a pragmatic and attractive alternative. On several occasions, the CIA cooperated with intelligence counterparts from regional states, who for their own reasons also sought to keep their involvement in Cambodia discrete.

This book attempts to pull back the veil on the CIAs involvement in Cambodia, first during the Khmer Republic and then after the Vietnamese invasion, when it was largely channeled through the noncommunist Cambodian resistance. Although there are a modest number of titles covering recent Cambodian history, this is the first one to investigate at length CIA operations in that country. And aside from a single monograph in 1991, there are no English-language books on the noncommunist resistance. This book will hopefully be an important source for students of contemporary Southeast Asian history, the Second Indochina Conflict, and CIA paramilitary operations.

In one sense, this is really two separate stories separated by time, though not geography. And perhaps not surprisingly, most of the primary charactersfrom Cambodian royalty to Thai generals to CIA case officersmaintained their roles throughout these periods. To them, Cambodia might have had chapters spread over a quarter of a decade, but they were always part of a continuing saga. They are treated as such in this book.

Among the many who contributed to this work, I would like to single out some who were especially generous with their help and support. In the United States, thanks go out to Andy Antippas, Alan Armstrong, Kenton Clymer, Doan Huu Dinh, Jim Dunn, Dennis Elmore, Denny Lane, Jim Parker, and Nate Thayer. Warm thanks go to Barry Broman for sharing his thoughts over some delicious bowls of khao soi.

In Singapore, I would like to acknowledge the assistance offered by the library staff at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

In Thailand, Tony Davis, Mike Eiland, Bertil Lintner, Sorachai Montrivat, Roland Neveu, Veera Star, and Mac Thompson have my gratitude. Special thanks goes to the late Lieutenant Colonel Manit Nakajitti, who never failed to amaze me with his photographic memory and network of contacts.

In Cambodia, I have received constant encouragement and help from Chea Chheang, Sieng Lapresse, and Leng Sochea. I would like to thank Hassan Kasem, Hul Sakada, and Kong Thann for their assistance with translations and interviews. My warmest appreciation goes as well to Dien Del, Sam Oum, Hun Phoeung, Tepi Ros, and Riem Sarin, with whom I shared many meals and conversations. I would especially like to thank Dr. Gaffar Peang-Meth and General Suon Samnang for their patient recollections over the years.

The author reserves special thanks to Merle Pribbenow for his remarkable translations and infectious enthusiasm for Southeast Asian military history.

And finally, the author would like to thank his editor, Mike Briggs, for years of support in seeing this through.

Ken Conboy

Jakarta, Indonesia

November 2012

Acronyms

UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KANSAS

UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KANSAS