Heart of Dryness

Heart of Dryness

HOW THE LAST BUSHMEN CAN

HELP US ENDURE THE COMING

AGE OF PERMANENT DROUGHT

JAMES G. WORKMAN

Copyright 2009 by James G. Workman

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Walker & Company, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10010.

Published by Walker Publishing Company, Inc., New York

All papers used by Walker & Company are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. The manufacturing pro cesses conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

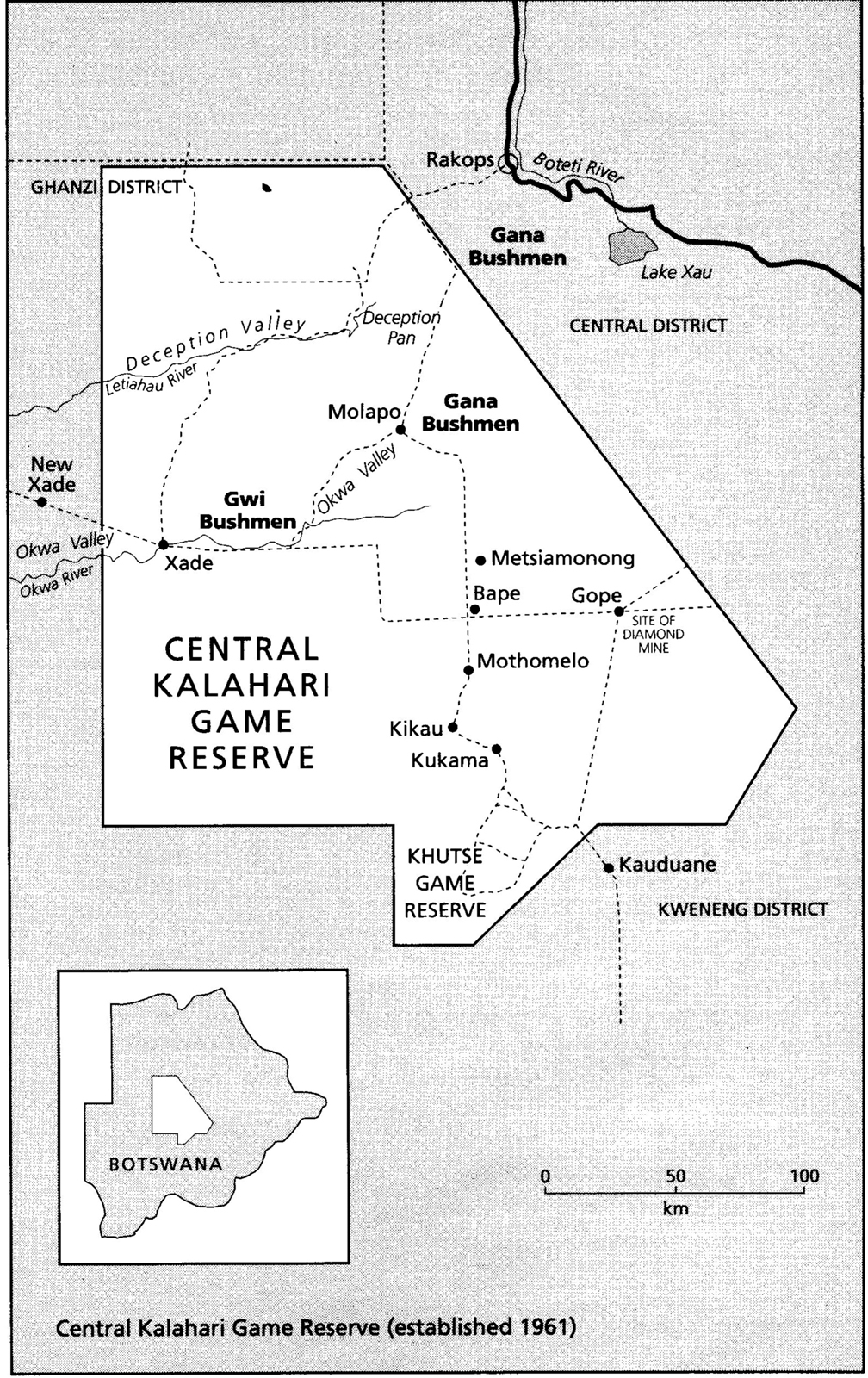

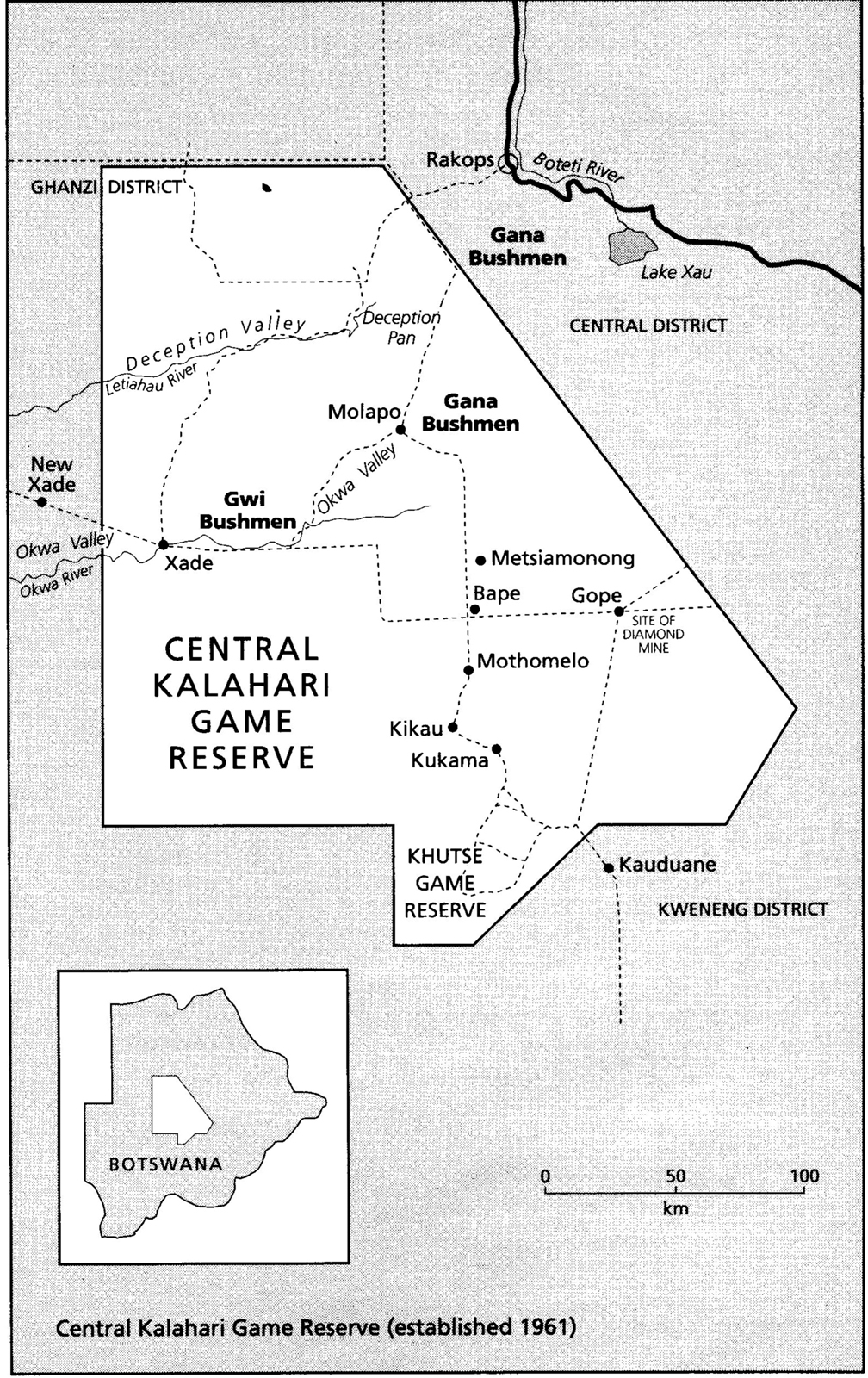

Botswana map: Sandy Gall

Map of water disputes in southern Africa: Peter Ashton

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Workman, James G.

Heart of dryness : how the last bushmen can help us endure the coming age of permanent drought / James G. Workman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-0-802-71961-4

1. San (African people)Social conditions. 2. San (African people)Government relations. 3. San (African people)Land tenure. 4. Indigenous peoplesEcologyKalahari Desert. 5. DroughtsKalahari Desert. 6. Desert ecologyKalahari Desert. 7. Water conservationKalahari Desert. 8. Kalahari DesertSocial conditions. 9. Kalahari DesertEnvironmental conditions.

I. Title.

DT2458.S25W67 2009

305.896'1dc22

2009005611

Visit Walker & Companys Web site at www.walkerbooks.com

First U.S. edition 2009

1 3 5 79 10 864 2

Designed by Rachel Reiss

Typeset by Westchester Book Group

Printed in the United States of America by Quebecor World Fairfield

To my father,

who provided sturdy roots,

and my mother,

who gave me restless wings.

It is scarcity and plenty that make the vulgar take things to be precious orworthless; they call a diamond very beautiful because it is like pure water,and then would not exchange one for ten barrels of water. Those who sogreatly exalt incorruptibility, inalterability, etc. are reduced to talking thisway, I believe, by their great desire to go on living, and by the terror theyhave of death. They do not reflect that if men were immortal, they themselveswould never have come into the world.

GALILEO, DIALOGUES

Contents

Water Disputes in Southern Africa

ONE STINKING HOT DAY DURING THE austral summer of 2002, the sovereign Republic of Botswana dispatched twenty-nine heavy trucks and seven smaller vehicles to converge on southern Africas arid core. To reach their designated target, the drivers had to traverse one of the most kidney-jarring, axle-snapping, sand-blasted, and sun-burned landscapes on Earth. The destination lay at the heart of what local languages translate as the Always Dry. Others call it the Great Thirstland. On maps it is labeled the Kalahari Desert.

The convoy ground through flat savanna as drab bunchgrass and thorn trees rolled past the windows. Only the rare sight of springbok or ostrich broke the monotony. Eventually the vehicles crossed an invisible threshold and entered a territorial reserve inhabited by bands of indigenous people known as the Gana and Gwi Bushmen.

For tens of thousands of years Bushmen and their ancestors had thrived in this unforgiving landscape. According to geneticists, linguists, and ecological scientists, these people constituted the remnants of the worlds oldest and most successful civilization.

For hour upon hour, the top-heavy vehicles jerked and careened forward as their fat wheels churned through the sand. That sand could reach 162 degrees on the surface, and in the peak of the day the heat expanded air pockets between the coarse grains, making the sand so soft and loose that even 44s bogged down. Drivers who let enough air out to increase rubber-to-sand traction increased their risk of a punctured tire. The maddening route grated on nerves already exposed by the unpleasant task they had to perform. And yet it was not all gloom and sadness. Indeed, the camaraderie lifted their spirits and brought playfulness to their character. Since no one wanted to be a failure, the convoy made a game out of their assignment, and it became a marvel to watch them display their prowess in attempting to outdo each other as the jocular drivers raced each other toward the center of the Kalahari, unable or unwilling to turn back.

Their assignment had been carefully mapped out in advance. Execution of orders was intended to be swift and unemotional. Sources would later differ about the degree of intimidation or physical violence involved, but some officers carried loaded weapons, for there could be no further negotiation with any of the remaining inhabitants.

Those still-intact bands of a thousand or so Gwi and Gana living at the center of the Kalahari felt confident in the ancient desert home from which they, unlike so many Bushmen, had never been driven. But even they owed their political asylum to international mercy. In the decade after the Second World War, upon learning how Israel was founded as a refuge for European Jews, Bushmen sought from England an equivalent for Africas genocidal victims. Listen to the weeping of a race which is very tired of running away, they pleaded. Give us a piece of land, too. Give us a piece of land where our women will not be taken from us.

In 1961 several British colonial officials leaned over a crude map of Botswanas sand-filled heartland, scratched straight lines into a twenty-thousand-square-mile trapezoid, and proclaimed the Central Kalahari Game Reserve. In doing so they drew upon the precedent of Americas protected parks, refuges, and forestswilderness areas set off-limits from development and kept uninhabited by people. But on this particular landscape, rather than seek a pristine virgin ecosystem, British officials planned to reserve sufficient land for traditional land use by hunter-gatherer communities of the Central Kgalagadi where the last surviving bands could develop on their own terms, free from relentless persecution to near extinction. Inside that hunter-gatherer haven, a thousand Bushmen clung fast to their autonomy in places with names translated as Vulture Water, Fossil Creek, Kneel to Drink, and Nowhere. Within their sanctuary Bushmen maintained a cultural identity unto themselves; they enjoyed a proud political autonomy that for various reasons annoyed and even threatened the more powerful surrounding Botswana republic. Outsiders referred to these central Kalahari Bushmen as the Last of the Firsta distinction the approaching convoy planned to end.

Despite early popular reports of their existence in a Lost World, Kalahari Bushmen were never mythical Children of Nature, sealed off from surrounding economies in an airtight bubble. Men occasionally walked out to work distant mines or ranches, while others trickled back and forth to exchange meat and skins for tea, tobacco, marijuana, blankets, and colored beads. Far-ranging hunters beat fence wire into arrow tips, pounded metal into spear heads, and made quivers from scavenged plastic PVC pipes. Like all of us, they adapted to available resources. Yet as the reserves sole human occupants, Bushmen had not been overwhelmed by the currents of the outside world. If anything, small groups of semi-nomadic pastoral tribes like the BaKgalagadi, arriving four hundred years ago, had been transformed to adopt the dryland survival skills and indigenous intelligence of the Kalaharis original inhabitants. So the British mandate never intended to preserve the Bushmen of the Reserve as museum curiosities and pristine primitives, but to allow them the right of choice of the life they wish to follow.

Next page