PUBLIC WATERS

Green River Lakes, Wyoming headwaters of the Colorado River. Courtesy of Rita Donham / Wyoming Aero Photo.

PUBLIC WATERS

LESSONS FROM WYOMING FOR THE AMERICAN WEST

ANNE MACKINNON

2021 by the University of New Mexico Press

All rights reserved. Published 2021

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-8263-6241-4 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-8263-6242-1 (electronic)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress.

Cover photograph courtesy of Rita Donham / Wyoming Aero Photo.

Maps by Rachel Savage, Casper, WY

Designed by Felicia Cedillos

For Cy and Wig

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I have been lucky to interview everyone who served as Wyoming state engineer since 1963: Floyd Bishop, George Christopherson, Jeff Fassett, Dick Stockton, Pat Tyrrell, and Greg Lanning; and almost every Wind River tribal water engineer: Kate Vandemoer, Wold Mesghinna, Gary Collins and Mitch Cottenoir. Ive been welcomed to meetings by members of their respective boards, including Earl Michael, Bill Jones, Randy Tullis, Brian Pugsley, Mike Whitaker, Carmine Loguidice, Dave Schroeder, Craig Cooper, Loren Smith, John Teichert, Jade Henderson, and Kevin Payne on the Wyoming Board of Control; and John Stoll, Sandra CBearing, Dick Baldes, Scott Ratliff, Leslie Shakespeare, Merl Glick, Jeremy Washakie, Ron Givens, Kenneth Trosper, Pat Lawson, Howard Brown, and Garrett Goggles on the Tribal Water Board. Several have taken time to talk or tour ditches with me, plus review book drafts. Jeff Fassett, former Wyoming Water Development director Mike Purcell, and former Bureau of Reclamation Wyoming manager John Lawson spent countless hours explaining water to me.

Thanks to academic colleagues Stephen White and Dan Meltzer of Harvard University, and early funding from the Mark DeWolfe Howe Fund at Harvard Law School; to Kristi Hansen, Ginger Paige, Harold Bergman, and Nicole Korfanta at the University of Wyoming; in Germany, to Konrad Hagedorn of Humboldt University, Berlin, Insa Theesfeld of Martin Luther University at Halle, Andreas Thiel, Uta Schuchman; and to Elinor and Vincent Ostrom at Indiana University. And to colleagues at the Casper Star-Tribune, WyoFile, and WyoHistory.org who taught me a lot about Wyoming, especially Dan Neal, Joan Barron, Paul Krza, Katharine Collins, Tom Rea, and Nadia White.

Thanks to those who, in addition to the state and tribal officials above, were always ready to talk water: Dan Budd, Kate Fox, Larry Wolfe, Bern Hinckley, John Shields, Steve Wolff, Tom Annear, Chris Brown, Baptiste Weed, Berthenia Crocker, Geoff OGara, Ernie Niemi, Jodee Pring, Barry Lawrence, Jane Caton, Sue Lowry, Marion Yoder, Albert Sommers, Randy Bolgiano, Ron Vore, Jodee Pring, Jason Baldes, Kim Cannon, Dave Palmerlee, Keith Burron, Arch McClintock, John Jackson, Jennifer Gimbel, Jon Wade, Larry McDonnell, Ramsey Kropf, Dennis Cook, Jim Jacobs, and Pete Ramirez. Thanks also to those who, in addition to several people above, read book drafts and offered helpful comments: Ted Ballard, Jim Boddy, Mike Cassity, Carol Rose, and Emlen Hall. And to the staff at the University of New Mexico Press: Clark Whitehorn, Sonia Dickey, Katherine White, and James Ayers. Librarians at the Wyoming State Library; the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming; Cindy Smith and Suzi Taylor at the Wyoming State Archives; Laurie Lye at Casper College Library; Lida Volin at Natrona County Library; the county libraries in Buffalo and Wheatland; the Homesteader Museum in Powell; the Buffalo Bill Museum in Cody; and the archives of the Midvale and Shoshone Irrigation Districts were unfailingly helpful. Many thanks to my indefatigable citations and format editor, Josh Moro of Caldera Communications.

Finally, friends and family: MacKinnons Cecil, Steve, and Peter and their families; Petre Osmanliev, Bernie Barlow, Sarah Gorin, George Jones, Connie Wilbert, Reed Zars, Megan Hayes, Tom Arrison, Marion Yoder, Ann Rochelle, Jane Ifland, Will Robinson, Mary Katherman, Eleanor Bliss, Betsy Dodd, Nancy Ranney, and Betsy Weiss. And finally, I am ever grateful to my husband, Jon Huss, and son, Ted Huss, who staunchly supported my every foray into water matters.

All errors are mine.

INTRODUCTION

Believing fully in the doctrine that public waters should remain a public property, and that to grant private perpetual rights is to sacrifice the welfare of future generations.

ELWOOD MEAD, WYOMING STATE ENGINEER, 18901899

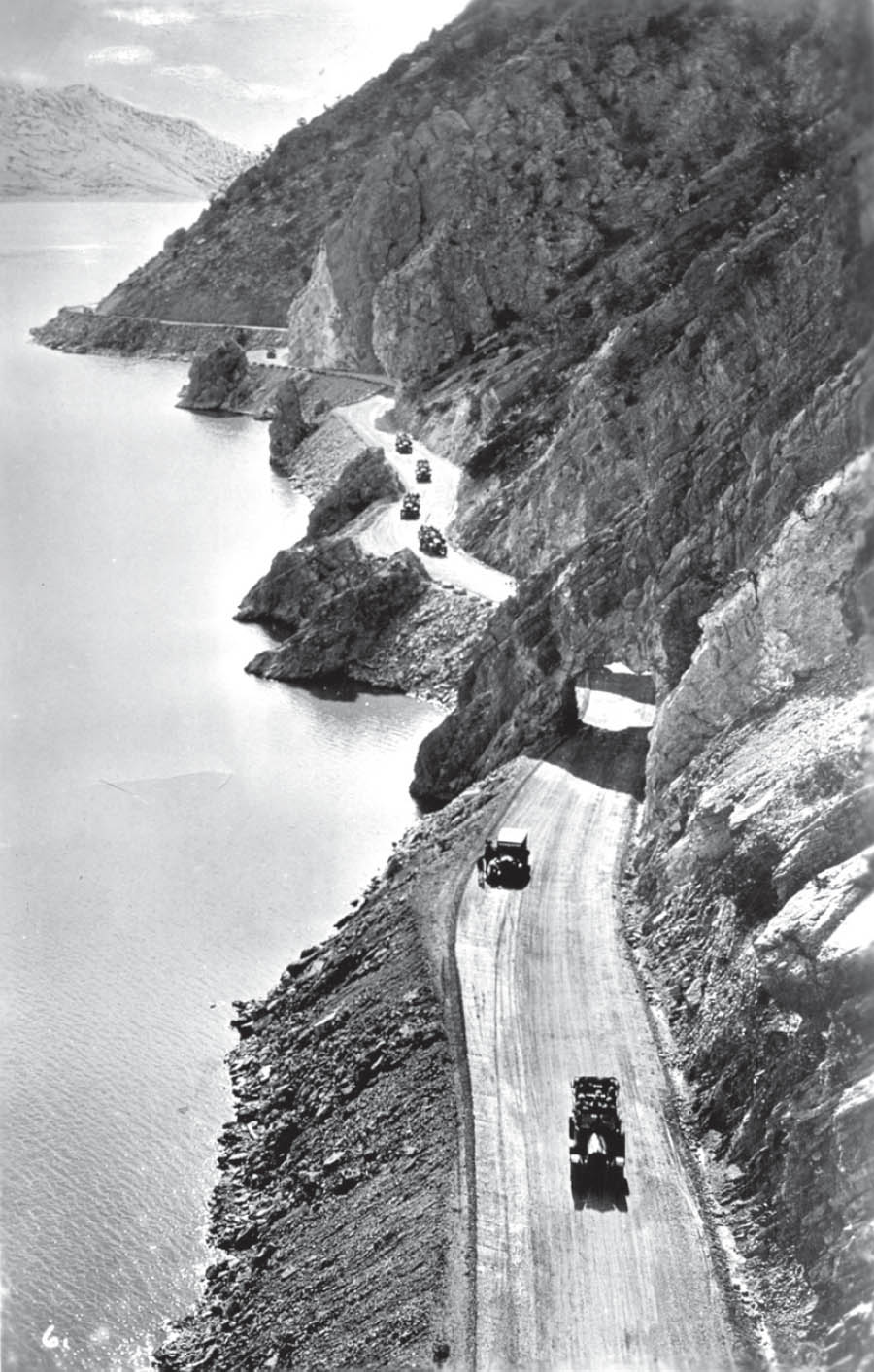

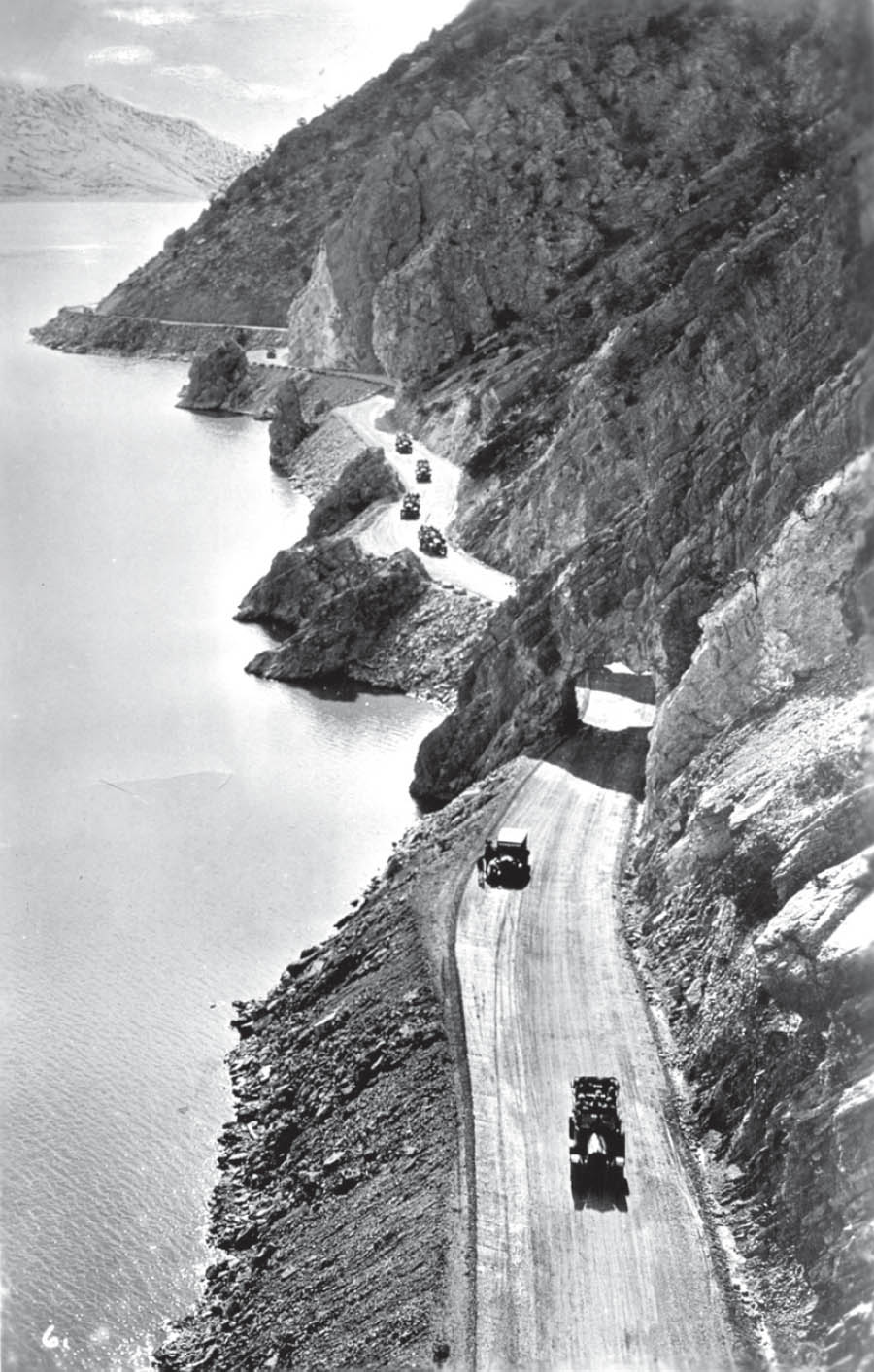

Heading to Yellowstone past Buffalo Bill Reservoir. Courtesy of Park County Archives.

UNCERTAIN WATER SUPPLY IS one of the most unsettling consequences of climate change and rapid population growth, the legacies of the twentieth century. Finding a way to govern the use of water so that this liquid resource can continue to sustain us and the world we live in is one of the major challenges of our time.

This book tells the story of how water has been used, shared, and sometimes used until it was gone, under a system of rights to water in one state in the western US: the high, cold, and dry state of Wyoming, where mountains gather the snowpack that feeds rivers crossing the dry lands below. It is the story of the rules people have made about using water, in a secluded place where the story is easy to trace.

Water is not to be taken for granted. It moves among us all, coursing through an endless cycle yet possible to deplete at any point on land where people might try to use it. And it can be hard to preclude people from using it. So one persons water use affects the water use of others. It creates interdependence among people. It creates interdependence between people and the natural world. How water is used affects the well-being of whole societies and landscapes. What we deal with, therefore, are fundamentally public waters. For the welfare of future generations, and of our own, those waters demand governance.

What has become of public waters? Over a century ago, the arid states of the US West, fearing monopoly private control over all access to water, adopted the idea that water resources should be public property. Then, to attract people and development, these states worked to put the use of public waters into private hands. State governments gave first comers, at no charge, a first right to use water, even when very little water was available; individuals could keep that rightperpetuallyif they regularly put the water to use. Not surprisingly, water users and many courts came to see a water right as simply a matter of private property.

Yet there remain odd twists to those private rights to use water. Not only can a water right be lost for non-use, but it can also be difficult to change to a new use or to use in a different place. Such changes typically shrink the amount of water that can be used. Private water rights are an incomplete property right, say the law treatises. That is because of the powers over water that remain in public handssuch as the crucial power to restrict changes to a new use or a new place. There is public oversight, with veto power, to ensure that the interdependency and overall social welfare issues inherent in water use are respected.