As

Precious

as Blood

The Western Slope in Colorados Water Wars, 19001970

Steven C. Schulte

University Press of Colorado

Boulder

As Precious

as Blood

2016 by University Press of Colorado

Published by University Press of Colorado

5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C

Boulder, Colorado 80303

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University.

This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

ISBN: 978-1-60732-499-7 (cloth)

ISBN: 978-1-60732-500-0 (ebook)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Schulte, Steven C., 1955 author.

Title: As precious as blood : the Western Slope in Colorado's water wars, 19001970 / Dr. Steven C. Schulte.

Description: Boulder : University Press of Colorado, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016019926| ISBN 9781607324997 (cloth) | ISBN 9781607325000 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Water rightsColoradoWestern SlopeHistory.

Classification: LCC HD1694.C6 S38 2016 | DDC 333.91009788/40904dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016019926

Cover photograph by Roy Tennant, FreeLargePhotos.com.

Preface

All of the great values of this territory have ultimately to be measured in acre-feet.

Wallace Stegner quoting John Wesley Powell, in Beyond the Hundredth Meridian

As Precious as Blood explores the ideas, strategies, and motives that animated Colorados Western Slopes attempts to maintain an adequate water supply. Western Colorado, settled by Anglo-Americans a generation after Colorados better-known mining frontier, was slow to build its necessary water infrastructure. Suffering from a combination of distance from sources of capital, small population, and little political power, the Western Slope of Colorado attempted to maintain its water supply in the face of challenges from Colorados Eastern Slope and nearby states.

Like a flowing stream, the current that connects Colorado politics across the generations is devotion to the lifeblood of reclamation. From the 1930s to the 1970s, Colorado engaged in a series of battles that collectively could be called Colorados twentieth-century water wars. The conflict catalyst in its simplest form may be reduced to this: the majority of Colorados precipitation arises high in the mountainous region west of the Continental Divide, in an area referred to as the Western Slope. However, the vast majority of the states population resides on the Eastern Slope, or Front Range, of Colorado, along what is referred to today as the Interstate-25 corridor stretching from Fort Collins in the north to Pueblo in the south.

From the beginning of human settlement in the lands that would become Colorado, the region shaped, bent, and broke civilizations according to the nature of their relationship to water supplies. From the Ancestral Puebloans to the Plains Indians to the Latino pioneers in the San Luis Valley, each culture wrestled with correlating its cultural horizons to a workable relationship with available water. With the start of the Colorado gold rush in 185859, it quickly became apparent that water would play the key role in determining the regions future. Within a few years, laws were enacted to control and distribute water that bore little resemblance to water laws and institutions in the eastern United States. The Wests imposing geography spawned an array of new laws dealing with natural resources, land distribution, and, above all, water. Water laws, however, would be fundamentally a product of the regions abiding aridity. As author Wallace Stegner phrased it, aridity and aridity alone united the American West across state boundaries.

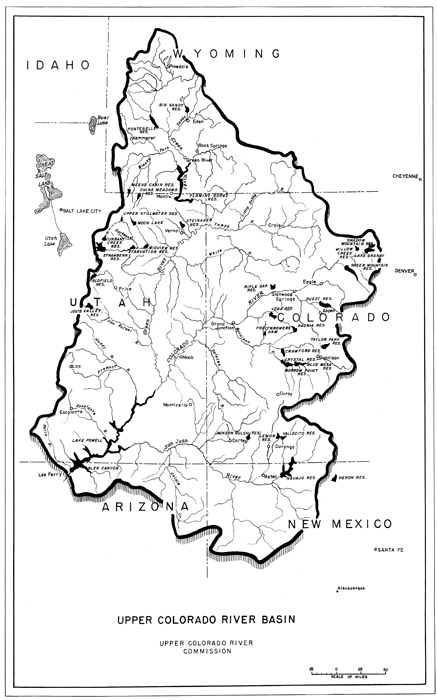

Figure 0.1. Upper Colorado River Basin. The map shows the principal federal water projects in Colorado and the Upper Colorado River Basin. Courtesy, Upper Colorado River Commission.

Noted water law scholar Charles Wilkinson observed that Colorado has always been the crucible for western water law and policy. thus the region is under constant pressure to cede additional water to more populous and politically powerful regions like Colorados Front Range. This issue is the source of much of the political friction that is the primary object of this study.

As Precious as Blood explains several important questions that animate Colorados water history, including how water emerged as the most pressing issue in Colorado history and why western Colorado began to equate trans-mountain diversions with a diminishment of its regional future. The strategies devised and implemented by Western Slope water officials are also explored and explained in some detail.

Western Colorados historical fears over its ability to sustain an adequate water supply stemmed from recognition that it lacked the political power to engage the more populated and politically potent Front Range on this issue. This is evident in the struggles of the Western Slope to receive what it considered equitable treatment from the Colorado Water Conservation Board in the mid-1950s during the apex of Colorados water wars. While western Colorado has exhibited an overall steady population increase, it has paled in comparison to the growth along the Front Range corridor where over two-thirds of the states population lives in the twenty-first century. This population trend translated into political power that favored eastern Colorado at every level of government, from municipal to federal. From 1914 to 1964 underpopulated western Colorado, with fewer than 200,000 people, maintained its own congressional representative. In 1964 the US Supreme Court mandated that states re-draw their congressional districts to reflect its one man, one vote decision. After 1972, the Western Slope no longer had a stand-alone representative as portions of eastern Colorado were added to the Fourth Congressional District. Reapportionment at the Colorado General Assembly level also hit the Western Slope hard, further undermining western Colorados political resources.

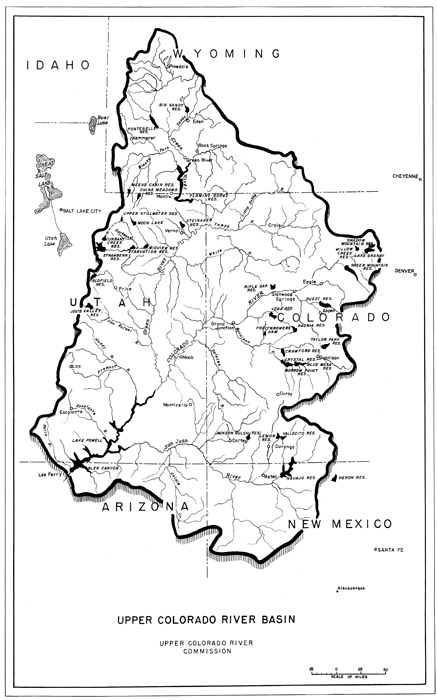

Figure 0.2. Aerial view of the Colorado River country on Colorados Western Slope, near Grand Junction. The Colorado River, its river of life, snakes through this harsh, arid country above DeBeque Canyon. Courtesy, Roy Tennant and FreeLargePhotos.com.

For most of the twentieth century, western Colorado successfully combated the more populous Front Range to maintain a degree of equity in water allocation. The Western Slope utilized many tactics to hold on to its water. A series of well-placed congressional representatives (from Edward T. Taylor to Wayne Aspinall) gave the region more power than its sparse population might have warranted. Effective tactics to delay Front Range water development efforts took many forms over the first two-thirds of the twentieth century. Above all, groups like the Colorado River Water Conservation District fostered regional solidarity against efforts by eastern Colorado to tap the waters of western Colorado. By remaining vigilant and fighting almost every trans-mountain diversion proposal, the region avoided the fate of becoming another CaliforniaOwens Valley, which saw much of its local water appropriated for the growth of the greater Los Angeles area.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of Association of American University Presses.