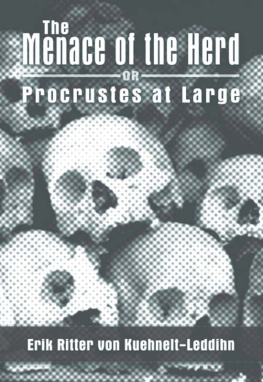

LEFTISM

From de Sade and Marx

to Hitler and Marcuse

ERIK VON KUEHNELT-LEDDIHN

RLINGTON HOUSEPUBLISHERS

RLINGTON HOUSEPUBLISHERS

NEW ROCHELLE, NEW YORK

Copyright 1974 Arlington House

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in connection with a review.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Erik Maria, Ritter von, 1909

Leftism: from de Sade and Marx to Hitler and Marcuse.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. LiberalismHistory. 2. DemocracyHistory. 3. ConservationHistory. 4. Political scienceHistory. I. Title.

JC571.K79320.510973-78656

ISBN 0-87000-143-4

Manufactured in the United States of America

To the Noble Memory of Armand Tuffin, Marquis de la Rourie

Courageous Fighter for Liberty

Ardent Admirer of America

Bitter Foe of the Jacobins

Friend of George Washington

Member of the Order of the Cincinnati

Contents

Preface

The author of this tome thinks that he owes it to his readers to declare his baggage, to say a few words about the purpose of this book as well as about himself.

I am an Austrian with a rather varied background and a good share of unusual experiences. Born in 1909 as the son of a scientist (radium and X-ray) who died as a victim of his research work, I traveled quite a bit as a young boy and acquired a knowledge of several tongues. Today I read twenty languages with widely varying skill and speak eight. At the age of sixteen I was the Vienna correspondent of the Spectator (London), a distinguished weekly founded by Addison and Steele. Engaged in the study of law and Eastern European history at Vienna University at the age of eighteen, I transferred a year later to the University of Budapest (M.A. in Economics, Doctorate in Political Science). Subsequently I embarked on the study of theology in Vienna, but went to England in 1935 to become Master at Beaumont College and thereafter professor at the Georgetown Graduate School of Foreign Service from 1937 to 1938. I was appointed head of the History Department in St. Peters College, Jersey City (1938-1943) and lecturer in Japanese at Fordham University. Until 1947 I taught at Chestnut Hill College, Philadelphia. These studies and appointments were interspersed with extensive travels and research projects, including the USSR as early as 19301931.

During my years in America I traveled in every state: Only southeastern Oregon and northern Michigan alone are still my blank spots. In 1947 I returned to Europe and settled in the Tyrol, halfway between Paris and Vienna, and between Rome and Berlin, convinced that I had to choose between teaching and research. From 1949 onward I revisited the United States on annual lecture tours. Since 1957 I have traveled every year either around the world or south of the Equator.

One of my ambitions is to know the world; another one is to do research in arbitrarily chosen domains serving the coordination of the various branches of the humanities: theology, political science, psychology, sociology, human geography, history, ethnology, philosophy, art. I have a real horror of one-sided, permanent specialization. I am also active as a novelist and painter. My books, essays, and articles have been published on five continents and in twenty-one countries.

Introduction

So much about myself. The purpose of this book is to show the character of leftism and to what extent and in what way the vast majority of the leftist ideologies now dominating or threatening most of the modern world are competitors rather than enemies. This, we think, is an important distinction. Shoe factory A is a competitor of shoe factory B, but a movement promoting the abolition of footwear for the sake of health is the enemy of both.

In the political field today this distinction, unfortunately, is less obvious and largely obscured by a confusion in semantics. This particular situation is bad enough in Europe, but it is even worse in the United States. This state of affairs, in turn, has adversely influenced the foreign policy of the United States which in the past and in the present not only has been determined by whatreally or only seeminglyis Americas self-interest, but also by ideological prejudices. Very often these ideological convictions coloring the outlook, the aims, the policies of those Americans responsible for the course of foreign affairs (not only Presidents, cabinet members, or congressmen, but also professors, radio commentators and journalists), have actually run counter to Americas best interest as well as to the very interest of mankind.

There is no reason to believe that ideologiesi.e., coherent political-social philosophies, with or without a religious backgroundhave come into play in America only during this century when America was I think that the nascent United States of the late eighteenth century was already in the throes of warring political philosophies showing positive and negative aspects. Even then the ideological impact of these ideas was keenly felt in Europe where, I must sadly admit, their inner content was often promptly misunderstood and perverted. The American War of Independence had an undeniable influence on the French Revolution and the latter, in the course of the years, had a deplorable impact on America.

Still, it is only in the twentieth century, in our lifetime, that the United States decisively intervened in world affairs and that Europe suddenly found herself on the receiving end of American foreign policy. Decisions made in Washington (with or without the advice or the prodding of refugees) affected Central Europewhich I consider my homedeeply and often adversely. The long years which I more or less accidentally spent in the United States made me realize the origins, the reasons, the psychological roots of the Great Euramerican Misunderstanding which, as one might expect, has several aspects: (1) the lacking self-knowledge of America, (paralleled by the nonexistence of self-knowledge of Europe); (2) the American misinformation about Europe (plus the European ignorance of America); and (3) the totally deficient realization of where we all now stand historically, what the big, dynamic ideologies truly represent, and how they are related to each other. And let us not overlook the fact that these three points are all somewhat interconnected, since both America (or, better still, the English-speaking world) and Europe (or, more concretely, the Continent) cannot be properly understood without an excursion into the field of ideology. Even the folklores are deeply affected by philosophies. A sentence such as One man is as good as any other man if not a little bit better reminds one automatically of a certain sector of American sentiment. It smacks of Sandburgian folkloric romanticism. On the other hand the words suum cuique (to everybody his due) are still inscribed at Innsbrucks law school. Yet it is equally true that Ulpians great legal principle also makes sense to a number of Americans while egalitarian notions today are rampant in Europe. The Atlantic Ocean, no less than the Channel, is shrinking and, slowly but surely, our confusions are fusing. To make matters worse, our respective semantics are still far apart.

The positive and constructive understanding between America and Free Europe is no less necessary than the realization of what political and economic order is good, right, fruitful. Therefore, this book tries to serve a double purpose: the reduction, if not the elimination of the Great Intercontinental Misunderstanding as well as the Quest for Truth which entails an expos of the multifaced, multiheaded enemy which is

Next page

RLINGTON HOUSEPUBLISHERS

RLINGTON HOUSEPUBLISHERS