Contents

Guide

To those men and women who blazed

the aerial trail between the wars.

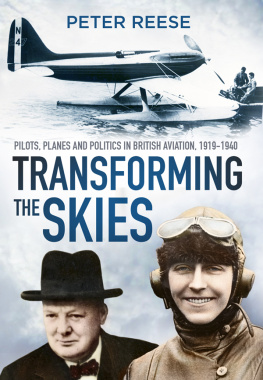

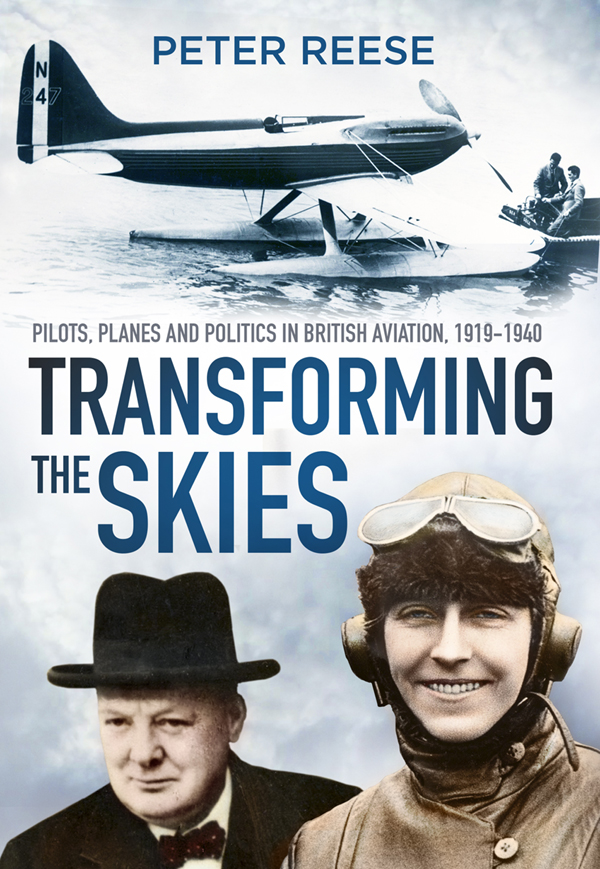

Cover illustrations

Front: The Supermarine 56 with its Rolls Royce R engine; Winston Churchill (authors collection); Amy Johnson (authors collection) Back: Mitchells Supermarine Spitfire Mark 1 (Digital image by Paul H. Vickers)

First published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Peter Reese, 2018

The right of Peter Reese to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8727 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am extremely grateful to many organisations and people for their immense help.

Above all I required a specialist aviation collection, which I found in the National Aerospace Library at Farnborough with its world-class collection of published and unpublished sources. There I have enjoyed the ready assistance of Chief Librarian Brian Riddle with his noted enthusiasm and encyclopaedic knowledge. I have also received immense help from Christine Woodward and latterly the kind and utterly professional Tony Pilmer, including his work on the index.

As on many other occasions, I have also worked in the Prince Consorts Library at Aldershot with its fine military collection, including aviation, where the staff are my firm friends of long acquaintance.

Further help has been received from the National Archives, the RAF Museum at Hendon, the Farnborough Air Sciences Trust Museum and the Royal Aeronautical Society (in particular for its original illustrations).

With regard to notable individuals, I am indebted to Mrs Jennifer Prophet for her early reading of the book and editing its text along with technical help from her son, Charles Prophet; Paul Vickers, historian and author, for ideas with titles and much more besides; Linda Mansell for her valued computer skills and great patience with my scrappy longhand; Tim Winter for illustrative sources; Frances Bean for additional typing; Stewart Davis for aerodrome maps; Dave Evans for other written material; and the late Nigel Legge for extensive discussion and valued advice.

As for the invaluable contribution of a publisher, I wish to acknowledge the faith and support of The History Press and in particular its commissioning editor, Amy Rigg and project editor Rebecca Newton.

Finally, my indefatigable wife Barbara, for being what she is, for organising our complex home affairs while I have been absent in libraries and for listening and then giving her acute reactions to my early drafts.

I alone remain responsible for any errors and deficiencies.

Ash Vale, autumn 2017

PROLOGUE

After my recent book about the pioneering figures and events that shaped British aviation from the beginning of flight to the movement in 1914 of the Royal Flying Corps detachments to France, I felt I was almost predestined to consider what followed.

Predictably I found that the First World War had its official and unofficial histories, biographies and pilots accounts (from both sides) about their aircrafts performances and their tactics in attempting to gain command of the air. Following such tales of high adventure, sacrifice and loss, I never expected the period between the wars to have been capable of attracting comparable attention or of being of equal or greater interest to the pioneering years of aviation prior to the war. It was therefore to my considerable surprise that, although it has drawn little literary attention so far, I found it packed with graphic incidents of genuine significance to the development of aviation and the survival of the British state during the Second World War. In short I discovered it was a magnificent story waiting to be told.

At first, I doubted whether anything could equal the advances made by the early aviators from their first flights measured in feet and seconds to the genuine cross-country performances of the aircraft that flew across to France in 1914. Yet, I quickly came to realise the far greater technological achievements of the interwar period. Although in its initial stages the disinterest shown towards British aviation prior to 1914 was repeated, with the role of the air force again questioned and the British aircraft industry shrinking in both size and capability, it could not last. By the mid 1930s the Royal Air Force faced likely attacks from a formidable new opponent and was compelled to enter into a breakneck race in which aeronautical developments went beyond the imaginings of the earlier pioneers. For such reasons I began to understand that this was indeed the time where British aviation came of age.

I also learned that the events of the interwar years went far beyond jostling for military advantage, including as they did such issues as the birth and expansion of British civil aviation, the building of huge airships before their final rejection, and the familiarisation of aeroplanes to ordinary men and women in Britain. Even so, it was the countrys involvement in the Schneider Trophy competitions, bringing major advances in both airframe and engine technology, that enabled Britains Royal Air Force to develop from a threatened and backward service to one whose balanced forces could meet assaults from a country that viewed air power as a major weapon of war.

Such was the speed and extent of the technological advances during this time that eminent scientist Sir Harry Garner called them discontinuities rather than the result of gradual improvements.

While he acknowledged that much of the progress was due to a steadily growing knowledge of materials, structures, aerodynamics and engine design, he identified other inventions bringing radical alterations (discontinuities) to the design of the aeroplane, such as unbraced monoplane construction that replaced the heavily braced biplane, and the gas turbine (rather than the piston engine) invented in Britain by Frank Whittle and tested in 1937 although this would not play a substantial role until late in the Second World War.

The piston engine shouldered the lions share of wartime missions and among the regular advances that Garner saw as transforming its performance and reliability were improved air-cooled radiators, superchargers and constant speed propellers, together with improved fuel that gave its bombers an increase of up to 70 per cent in the ratio of power to weight compared with those in the First World War.

Such advances became ever more significant when the weight of airframes was reduced by using improved materials, e.g. alloys with stressproof qualities (compared with the previous wood and canvas) leading to dramatic increases in wing loading. Speaking after the war as an expert on aircraft engines, Roy Fedden maintained that aviation had and will continue to have a more far-seeing effect in other fields of material endeavour than any other previous single development.